By Joseph Daher

Lebanon’s central bank governor Riad Salameh has long been protected by the country’s political elite, but the international allegations he faces, including embezzlement, could provide an opportunity for justice & accountability, argues Joseph Daher.

Riad Salameh, the governor of the Lebanon’s central bank who is considered one of the main actors responsible for the financial crisis which has plagued the country since 2019, is facing allegations of crimes including embezzlement, money laundering and tax evasion in separate probes in Lebanon and Europe.

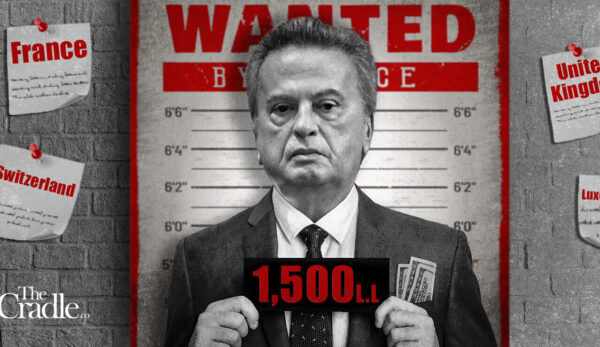

France, Germany and Luxembourg seized assets worth $130 million in March 2022, in a move linked to a French investigation into Salameh’s personal wealth. In February 2023, the Swiss newspaper SonntagsZeitung reported that a large share of the $300-500 million that Salameh is accused of having embezzled ended up on the accounts of 12 Swiss banks.

On 16 May, French prosecutors issued an international arrest warrant for Salameh for corruption, forgery, money laundering and embezzlement. Following this, Lebanon received an Interpol red notice for Salameh, in addition to being informed by Germany of an arrest warrant for him over “corruption, forgery, money laundering and embezzlement”.

Salameh stated that he would appeal against the Interpol red notice associated with the arrest warrant issued by the French judiciary. He also indicated that he would resign “if a judgment is handed down” against him, and confirmed that he would in any case leave office at the end of his term on 31 July.

Public enemy

Riad Salameh is one of the world’s longest-serving central bank governors. He has been head of the Banque du Liban (BdL) since 1993 and was nominated by then prime minister and wealthy businessman, Rafic Hariri, whose portfolio Salameh handled at Merrill Lynch.

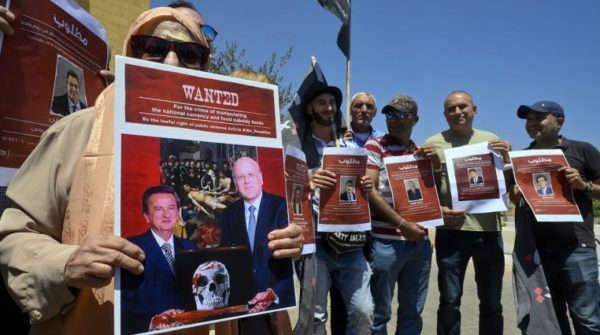

Salameh is considered the central architect of the Ponzi scheme which since the early 1990s encouraged Lebanese banks to offer high interest rates to attract US dollar deposits and then lent the money to the government. He was unsurprisingly one of the main targets of the Lebanese protest movement, and continues to be until today.

The governor also had personal wealth hidden overseas. In August 2020, a joint OCCRP-Daraj investigation found that his offshore companies had invested in overseas assets worth nearly $100 million, including a $4.1 million luxury apartment in London. His son, Nadi, was also able to send more than $6.5 million abroad, while banks in Lebanon imposed draconian restrictions on withdrawals and depositors saw their savings slip away as the market value of the currency plummeted from LBP 1,500 to the dollar pre-crisis, to around LBP 95,000 to the dollar today.

The absence of confidence in the banking system has resulted in the expansion of a chaotic cash-based economy. The World Bank stated just this month that “the systemic failure of Lebanon’s banking system and the collapse of the currency have induced a pervasive dollarized cash economy estimated at almost half of GDP in 2022”.

Protection by the elite and judiciary

Despite the accusations over multiple crimes, Salameh is still acting as the governor and is also the president of the special investigation committee for money laundering and financing of terrorism. This has all been due to the support and protection provided by large sections of the Lebanese ruling class.

At the end of 2021, Prime Minister Nagib Mikati stated that Riad Salameh should remain in position as governor despite embezzlement probes at home and abroad. He declared in a clear sign of support to Salameh, that “one does not change their officers during a war”, while adding that the investigations against the governor were “being used in politics”.

Another strong supporter of Salameh is the speaker of parliament, Nabih Berry. In April 2020, he warned against removing him because this would endanger the Lebanese pound’s stability and threaten deposits in banks.

The influential Maronite Patriarch, Bechara Boutros al-Rai, also backed Salameh by saying that criticism of Salameh would only hurt Lebanon.

Moreover, the ruling elite protected him from judicial prosecutions as the investigation into the governor have been continuously sabotaged in Lebanon. In January 2021 for instance, Ghassan Oueidat, the country’s chief prosecutor of Lebanon’s highest criminal court – considered as close to the Hariri camp – stopped an investigation involving Salameh.

In September 2022,the Court of Cassation granted Salameh and all central bank’s employees immunity in any case related to violations of the Code of Money and Credit, which regulates banking activities, except upon the central bank’s request. This ruling provided him with a strong immunity as any further investigation needed Salameh’s agreement. This did not, however, involve breaches of the Penal Code, which are part of the charges against him in the Lebanese probe.

More recently, the Council of Ministers dismissed two French lawyers appointed to defend the country’s interests in Salameh’s corruption case on the pretext that one of the lawyers is a member of the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism, which “is suspected of advocating Zionist ideas”. This was clearly to prevent the release of additional evidence for new investigations that would implicate the Lebanese political and economic elites, as well as those close to them.

Nevertheless, since the latest international arrest warrants it seems the ruling elite have become more silent in their defence of the governor, while others have called for his resignation and replacement. In the aftermath of this turnaround Salameh has said that it is the political class that should be held accountable, not him.

The need for accountability

It must be said that Riad Salameh is not an isolated case. The Lebanese ruling elite have intervened on numerous occasions to paralyse the work of the justice system in order to protect their political interests and prevent any accountability for their crimes.

Even Lebanon’s judiciary is not independent as the ruling political elite exert large influence over judicial appointments, jurisdiction, processes, and decisions which relate to corruption. A prominent example is the continuous attempts to bury the investigation into the Beirut port blastthat killed 220 people and devastated swathes of the city.

The tragedy was found by Human Rights Watch to be the result of the government’s failure to protect the fundamental right to life and even pointed to the potential involvement of senior political and security officials in Lebanon.

Given the context and a history of constant obstructions of justice in Lebanon, the French prosecution could, hopefully, represent an opportunity for accountability. It may also lead to challenging the system of immunity established by and for the ruling political and economic elite that is responsible for the catastrophic socio-economic situation in the country.

Source: New Arab

Joseph Daher teaches at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and is an affiliate professor at the European University Institute in Florence, Italy, where he participates in the “Syrian Trajectories” project. He is the author of “Syria after the Uprisings, The Political Economy of State Resilience”.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.