A recent ruling by a French court ordering Lebanon’s Saradar Bank to pay $2.8 million to a client is encouraging Jordanian businessman Talal Abu-Ghazaleh to sue another Lebanese bank to recover his deposits. Abu-Ghazaleh claims the money is there somewhere in Europe . He claims that following the financial crisis the Lebanese banks transferred all their funds to outside Lebanon, mainly Europe

By Dalal Saoud

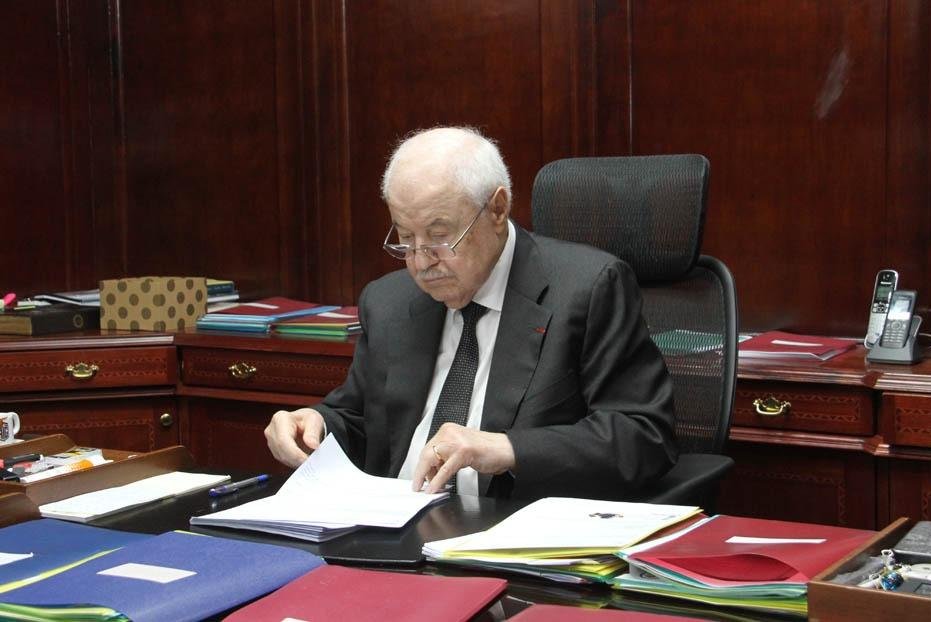

BEIRUT, Lebanon, — Jordanian businessman Talal Abu-Ghazaleh, who is among more than 1.4 million depositors with savings stuck in Lebanese banks, said he is determined to proceed with lawsuits against a bank and the central bank governor to recuperate his millions in assets on the basis of “misuse.”

Abu-Ghazaleh’s case illustrates the ordeal facing Lebanese and foreign depositors, who own, according to the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, some $107.28 billion in Lebanese banks as of the end of March.

“No matter how long it is going to take, I am going to continue to pursue recovering my assets,” Abu-Ghazaleh told UPI during an interview in Amman, Jordan, earlier this month. “I did not want to leave the subject without putting on record that there has been such a misuse of my deposits and that I would document through court the fact that they owe me that money.”

A self-made businessman, Abu-Ghazaleh decided to sue Société Générale de Banque au Liban to recover his deposits, which so far amount to “$45 million” and are “increasing because of the accruing interests.”

Capital frozen

Shortly after the outbreak of a popular uprising on Oct. 17, 2019, Lebanese banks imposed capital restrictions, including freezing deposits of dollars, limiting withdrawals and blocking transfers.

However, billions of U.S. dollars have reportedly been transferred abroad by influential politicians and businessmen before and during the crisis, despite the restrictions. Although these transfers were legal, they were made in a discriminatory and unethical way, financial experts and politicians say. There was still no official confirmation about the total amount transferred or who made the transfers.

Lebanon has been sinking deeper into economic crisis, described by the World Bank as one of the worst in the world since the mid-19th century. The Lebanese pound has lost more than 90 percent of its value, poverty and unemployment is high, and inflation has skyrocketed, further impoverishing the population.

People woke up one day to the painful reality that they had no access to their funds and couldn’t withdraw money from the banks, which began to impose their own rules in the absence of any government measure to regulate the financial sector.

The parliament has failed to pass a formal capital control law. Deputy Prime Minister Saade Chami announced last week that officials have finally agreed on the size of the country’s massive financial losses, estimating them at some $69 billion.

Chami said the government, central bank, banks and depositors will bear the burden of the losses but did not disclose how they will be distributed.

The time when dollars used to flow in the country is over. Banks, which in 2016 began to offer generous interest rates up to 20 percent to keep attracting deposits in U.S. dollars, are now short on foreign currency and can no longer pay their depositors.

The 2011 civil war in Syria, the growing power of Iran-backed, heavily armed Hezbollah and its expanded role in the region has pushed away the Gulf countries — Lebanon’s traditional backers. In addition, widespread corruption, mismanagement and endless political bickering has left the country in disarray.

The government, for the first time in the country’s history, decided in March 2020 to default on a $1.2 billion Eurobond.

Resorting to courts

Having been deprived of their life savings, many depositors refused to keep silent and resorted to courts. Several lawsuits have been filed by depositors against Lebanese banks in Lebanon and abroad, including France, the United Kingdom and the United States, but none has reached a successful conclusion.

Abu-Ghazaleh filed a first lawsuit against SGBL in Lebanon, naming the bank’s president, management and shareholders and seeking that the bank’s assets be frozen for repayment of his deposits.

He said he wanted to “highlight the fact that there is default,” and to put on record that he has “a claim, and this claim remains and stands.”

“I am not worried about my money. I wanted the principle,” he said. “I was worried about the small depositors who are unable to do anything.”

As the legal battle continues, Abu-Ghazaleh said he decided to file a case in Paris against SGBL, as well as against Lebanon’s central bank and its governor, Riad Salameh, “to seize their assets in France.”

He added that he filed another case against SGB Jordan to seize shares owned by SGB Lebanon in the Jordanian Bank, noting that “SGB Lebanon shares in SGB Jordan represent 88% of the capital, while the remaining 12% is owned by Jordanian shareholders.”

SGBL did not reply to UPI’s questions about Abu-Ghazaleh’s case and other banking issues.

Abu-Ghazaleh filed a first lawsuit against SGBL in Lebanon, naming the bank’s president, management and shareholders and seeking that the bank’s assets be frozen for repayment of his deposits.

He said he wanted to “highlight the fact that there is default,” and to put on record that he has “a claim, and this claim remains and stands.”

“I am not worried about my money. I wanted the principle,” he said. “I was worried about the small depositors who are unable to do anything.”

As the legal battle continues, Abu-Ghazaleh said he decided to file a case in Paris against SGBL, as well as against Lebanon’s central bank and its governor, Riad Salameh, “to seize their assets in France.”

He added that he filed another case against SGB Jordan to seize shares owned by SGB Lebanon in the Jordanian Bank, noting that “SGB Lebanon shares in SGB Jordan represent 88% of the capital, while the remaining 12% is owned by Jordanian shareholders.”

SGBL did not reply to UPI’s questions about Abu-Ghazaleh’s case and other banking issues.

A Nov. 19 ruling by a French court ordering Lebanon’s Saradar Bank to pay $2.8 million to a client, identified as a Syrian woman living in France, was described as an encouraging step for Lebanon’s bank depositors to turn to international courts.

Another Lebanese depositor, Bilal Khalifeh, who filed a case in the United Kingdom against Banque du Liban et D’Outre Mer to transfer $1.4 million abroad, was not as successful. On Friday, the British court ruled in favor of BLOM, saying it was not obliged to make such a transfer and has discharged its debt by issuing a check to Khalifeh in Lebanon.

Saradar Bank and Khalifeh said they will appeal the rulings.

Lebanese banks have resorted to terminating the accounts of clients claiming their money via courts of law by issuing banker’s checks and depositing them with a notary in Lebanon.

“These checks are like a piece of paper. No other bank will take them, and they cannot be cashed out in dollars,” the lawyer said. “The problem is to be able to withdraw the money from the bank… and the banks don’t have the money.”

Money ‘is there’

Abu-Ghazaleh, who owns an international accounting firm as part of his Talal Abu-Ghazaleh Organization for education and professional services, said he has “information that the money is there, somewhere. It is not in the bank but it is there.”

“Just before they [Lebanese banks] started feeling that there will be a financial collapse, they remitted it all outside, to Europe basically,” he said, adding that “the cover-up and helping the funds to be transferred outside was another crime.”

He maintained that “the small part” of the deposits was used to fund the government while the greater part has been deposited over a period of six months outside Lebanon before the 2019 crisis.

Lebanon’s successive governments, central bank and banks were all held responsible for using citizens’ deposits to help finance the government and cover public deficits.

A senior banking official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, argued that the banks “did not do wrong” and expressed concern over the need to treat depositors equally, regardless of the size of their deposits.

“Those who file a lawsuit, I should pay them and those who don’t, I don’t pay them?” the official told UPI.

Abu-Ghazaleh said the banking crisis “is the making of the Lebanese themselves” and has nothing to do with “the political or international crisis.”

“Lebanon is not bankrupt; Lebanon is mismanaged,” he said. “When you conspire with the banks to transfer billions secretly, and you think it can be kept secret, this is the problem.”

Priority remains to safeguarding depositors’ rights and funds as part of an economic recovery plan supported by the International Monetary Fund.

“If ever there comes a government which can enforce the law and say everybody who remitted money to bring it back, it [the problem] will be solved,” Abu-Ghazaleh said.

(UPI)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.