Raida Bitar is at breaking point, and so is the Beirut hospital she works in. The chief pharmacist’s eyes fill with tears as she opens cupboards normally filled with lifesaving medicines but which now sit empty.

“It’s like a nightmare,” Bitar says. “I have worked here for 16 years and this is by far the toughest time we have faced.

“Every day, you are depleted of your energy, depleted of your soul and depleted of hope. This is the first time in my life I have lost hope.”

A crippling medicine shortage is the latest symptom of a complex illness killing a once-great country. The crisis in Lebanon is so grave the World Bank believes it may rank as one of the top three economic calamities to strike any nation for the past 170 years, beaten only by Chile’s Great Depression in the 1920s and the onset of civil war in Spain in the 1930s.

.

Drivers sit in baking summer heat for hours in the hope of finding scarce fuel, citizens are banned from withdrawing their savings from the banks, the electricity system has stopped working, the currency has lost almost all its value and hyperinflation has sent the price of some foods soaring by 1000 per cent. If the price rises in Lebanon were replicated in Australia, a one-kilogram packet of sugar would cost about $15.

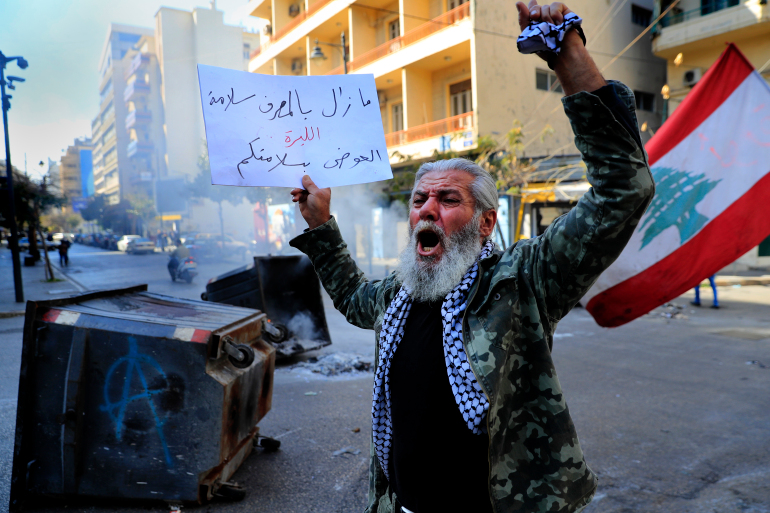

While anger at Lebanon’s leaders is palpable, one man also bears a heavy responsibility for the meltdown.

Riad Salameh has been governor of Lebanon’s central bank for an extraordinary 28 years and is the architect of the country’s financial mess. His most disastrous policy was to encourage more US dollars into the country by urging Lebanese citizens to deposit cash in banks on the promise of unrealistic double-digit interest rates. The Ponzi scheme collapsed in 2019 and the Lebanese are now banned from accessing their life savings.

“Before 2019, Salameh was the God of Lebanon,” says Hasan Illeik, a senior journalist at the newspaper al-Nahar. “We were the only paper always writing about what he was doing. Everybody was saying he’s the best genius in the world of economics, and we knew it was all heading for a collapse.”

Salameh, a former Merrill Lynch banker, is now being investigated by authorities in France and Switzerland. The latter is probing the alleged transfer of more than $US300 million ($408 million) in funds between the central bank and an offshore company with potential links to his brother, Raja. Salameh has denied any wrongdoing.

On Salameh’s watch, the value of the Lebanese pound (ЈLB) has plummeted. Only a few years ago, ЈLB1500 could be exchanged for $US1, but the rate is now a whopping ЈLB20,000 to the dollar. Lebanon’s GDP plunged from $US55 billion in 2018 to $US33 billion in 2020 — a contraction the World Bank describes as “brutal” and of a kind usually associated with wars.

Hyperinflation means a month’s worth of food for a family of five now costs four times Lebanon’s minimum wage. The price of one kilogram of fresh beef has soared from ЈLB15,000 to ЈLB160,575. Thirty eggs are 787 per cent more expensive than they were in the summer of 2019. One kilogram of rice has jumped from ЈLB2028 to ЈLB19,658.

Crisis at the supermarket: the spiralling cost of Lebanon’s groceries

Prices in Lebanese pounds

| Food Item | August 2021 | Summer 2019 | % change | |

| Tomato (1kg) | £7,574 | £1,175 | 544% 544% | |

| Cucumber (1kg) | £9,600 | £1,210 | 693% 693% | |

| Potato (1kg) | £8,093 | £1,039 | 679% 679% | |

| Red apples (1kg) | £13,762 | £2,260 | 509% 509% | |

| Banana (1kg) | £10,770 | £1,812 | 494% 494% | |

| Fresh beef (1kg) | £160,575 | £15,066 | 966% 966% | |

| Whole chicken (1kg) | £28,529 | £6,017 | 374% 374% | |

| Eggs (30 pieces) | £52,217 | £5,888 | 787% 787% | |

| Labneh (500g) | £41,026 | £6,035 | 580% 580% | |

| Akkawi white cheese (1kg packaged) | £119,851 | £19,040 | 529% 529% | |

| Milk Powder (2.5 kg box) | £120,833 | £27,836 | 334% 334% | |

| Rice (1kg packaged) | £19,658 | £2,028 | 869% 869% | |

| Flour (1kg packaged) | £4,933 | £4,301 | 15% 15% | |

| Sugar (1kg) | £15,749 | £1,182 | 1232% 1232% | |

| Butter (400g) | £52,886 | £6,413 | 725% 725% | |

| Olive oil | £376,852 | £46,527 | 710% 710% | |

| Sunflower oil | £159,516 | £10,700 | 1391% 1391% |

Table: Jamie Brown Source: Crisis Observatory

The rapid collapse has left Rafik Hariri University Hospital — the largest public hospital in Beirut — struggling to keep patients alive. Supplies of magnesium used to treat women with eclampsia have run out. So have the antibiotics given to people suffering septic shock.

“Until two hours ago, I didn’t have any adrenalin, which we might use for a patient who has a drop in blood pressure,” Bitar says. “Without that, they will die.”

Issa Khalil Bulbul’s parents must drive their son 85 kilometres from Tripoli to the hospital every three days to treat his failing kidneys, so every second day his father queues for hours to spend ЈLB250,000 on petrol.

“I had this card from the hospital to make me pass the queue but now it doesn’t work any more and I don’t have time to wait,” says his father. “Tell me, how can we survive?”

The hospital’s chief executive, Firass Abiad, has long moved beyond frustration “simply because frustration or anger is not conducive to surviving. I don’t think anyone in Lebanon would have told you that they expected things to get as low as they have. The rate of descent has been astronomical. We are in complete freefall”.

As the economic meltdown worsens and Beirut struggles to stitch itself back together after last year’s massive warehouse explosion, tens of thousands are fleeing a city once known as the Paris of the Middle East. The departures terminal of Beirut’s Rafic Hariri International Airport is packed from morning to night with families carrying multiple suitcases and hopes for a better life away from Lebanon.

The tragedy is that the exodus is being led by the bright youth who stand the best chance of overturning the corruption responsible for bringing the country to its knees.

Amin Timani, 28, volunteered to clean up the river of glass and debris choking Beirut’s streets following last year’s explosion and has helped hundreds of impoverished families since. For his troubles, the graphic designer was shot at close range with a rubber bullet during a protest seeking justice for the 218 people killed, 7000 injured and 300,000 rendered homeless by the port disaster. Blood spurted from Timani’s neck before he placed a hand over the wound and staggered to the nearest Red Cross centre. “I thought if I sit down I’m going to die because no one will have the courage to come and help me.”

Timani has had enough and will move to Germany this month. “They don’t give a shit about us,” he says of Lebanon’s leaders. “They don’t give you time to think about your future because you are so busy worrying about the day-to-day, like getting fuel just to go to work.”

The short drive to visit Timani at a coffee shop in north Beirut was delayed by long lines of cars waiting at depleted petrol stations. Some queues stretch for two kilometres and drivers can wait all day without reaching the pump. They lock their cars and walk home before returning the next morning.

Triggered by hoarding, smuggling, the sudden withdrawal of government subsidies and the inability of the cash-strapped state to import supplies, the fuel crisis turned deadly last month when a tanker exploded in the northern town of al-Tleil while Lebanese soldiers distributed petrol seized from the black market. Twenty-seven people burned to death.

Taxi driver Romeo Khalil arrived at a petrol station in Beirut at 3am last week but by midday was still not sure whether fuel would arrive at 2pm. “Every person in this country is angry,” he says. “It’s a bad situation and nobody cares about us.”

Sensing a chance to turn the crisis into a geopolitical opportunity, Hezbollah secretary-general Hassan Nasrallah has arranged three fuel shipments from Iran — a move which would normally infuriate the United States and lead to heavy sanctions for Lebanon but might be allowed to pass without punishment given the misery facing millions. Even Hezbollah’s strongest critics concede very few Lebanese people care where the fuel comes from. The first shipment is expected to dock in Syria and be sent over the border in trucks.

Lebanon’s electricity system was prone to power cuts before the economic crisis hit but some parts of the country get just two or three hours of state-provided power a day. People are forced to choose to live and work in darkness and stifling heat or access privately operated generators. However, the fuel shortage means there isn’t enough diesel to run the generators.

Abiad, the Rafik Hariri University Hospital chief, reveals the hospital has come within three hours of running out of fuel. “If we run out, our generators stop and our machines stop. Working like that, in any context, is dangerous. By international standards, you need to have a minimum of one month of fuel reserves. We are having some close calls, and you never know when one of them becomes a severe accident.”

Nearly two-thirds of the hospital’s physicians and one-quarter of its nurses have quit, with more expected to leave soon despite incentive and recruitment programs.

Abiad senses that even the diehards who have so far decided against leaving Lebanon are changing their minds.

“When our staff come to work, they find they can’t do a proper job because they don’t have the resources. They have to sit there helpless as their patients are withering away in front of them. They then finish work and go back home to a house where there is no electricity and spend the time they should theoretically be resting instead in their cars waiting four or five hours for petrol. Life has become a struggle at work and outside work.”

The United Nations recently allocated $US10 million ($13.5 million) to buy fuel for Lebanon’s hospitals and medical cold-storage facilities. The next concern is whether water supplies will be cut because of the lack of power needed to pump it.

“Electricity is the bare minimum — it is life,” says Omar Jheir, an Australian who owns the SIP cafe and Peck restaurant in Beirut’s trendy Gemmayzeh district.

The cafe was destroyed when the warehouse full of ammonium nitrate exploded at the nearby port. Jheir was seriously injured. “You don’t get a breath of fresh air between hits to fully recover,” he says of the pandemic, blast and economic crisis. “I’m keeping my business open and employ 25 people in my operations, so I am doing my part.”

Jheir reels off fond memories of “good years” in Lebanon like 2002 and 2003 where the economy was humming and Beirut buzzed with life. “Those years show what sort of potential exists here. The Lebanese know the potential of Lebanon and that’s why they are pissed off and angry because they know what could be.“

Up the road, restaurant owner Hassan Hammoud is recounting the August 4, 2020, explosion when he walks away, takes a sharp intake of breath and tries not to cry. Hammoud has scars on his limbs from that awful day and his business could only reopen thanks to crowd-funding, generous customers and a donation from PepsiCo employees for new windows worth $32,000.

Dar El-Gemmayzeh, which specialises in Lebanese cuisine, reopened its dining room earlier this year but Hammoud had to close it in August as the cost of generators soared.

“In June, the generator man told me, ‘Hassan you are going to have to pay ЈLB35 million this month’. That is huge. It doesn’t make sense. The generator is more expensive than the rent.” Towards the end of our interview, Hammoud received a text message quoting electricity supply for September at ЈLB150 million. All he could do was laugh.

“The Lebanese people adapt. We are told to adapt constantly, so we think what is happening now is normal. But this is not normal.”

What angers him most? “To see this mafia not giving a shit about us. All Lebanese leaders from day one [after the 1975-1990 civil war] in 1991 — the ones alive and the ones who are dead — all of them are responsible for what has happened.

“Frankly, my son is telling me every day that when he is 18, he will not live in what he calls this ‘rotten country’. This is a 10-year-old child. I don’t want him to lose opportunity. It’s too hard to let him live the experiences you have lived.”

CARMEN YAHCHOUCHY

Bitar, the hospital pharmacist, also sees no future in Lebanon for her eight-year-old son. “He doesn’t deserve this. He doesn’t deserve to live where people are sad all the time,” she says.

“I always used to think that no matter how hard things got in this country, it was just a phase and would pass — and I say that having lived through the civil war. But what I really fear now is that things are actually going to get worse. Where is the government’s plan to get out of this hell? Where are they? We can’t see them.”

Lebanon has been without a government since the administration led by Hassan Diab resigned just days after the August 2020 blast. President Michel Aoun invited Saad Hariri, the son of assassinated former prime minister Rafik Hariri, to form a new government but the talks collapsed. Diab became the caretaker prime minister, with caretaker ministers presiding over a failed state.

The latest prime minister-designate, billionaire businessman Najib Mikati, finally formed a cabinet on Friday ahead of national elections scheduled for May next year. Mikati has spent weeks negotiating the sectarian power-sharing agreement that ended the 15-year civil war in 1990 by guaranteeing influential positions to the country’s 18 religious sects. The scheme has allowed corruption to flourish and concentrates huge power within a small group of families and individuals.

“We need another system,” says Halime El Kaakour, an activist and university law professor. “We have been saying this for 10, 20 or 30 years, but this system is falling apart and it’s time to build another one. We are governed by the few, the old, the wealthy and the men.”

Kaakour, who will run in next year’s elections, cited a study of 42 villages which found there were no youths on their boards and just six women.

“Yes, I am tired physically, yes, I have mental and financial pressures, but I am a strong independent woman and more than ever I am willing to believe in change. I’m so confident things will change because the system cannot be sustained. It cannot hold when it is falling apart,” she says.

Kaakour believes the idea that last year’s explosion was a catalyst for change was misguided: “It wasn’t a trigger, it was a source of fear. Many lost not just their homes but also any hope of change after the explosion. They felt isolated because the state wasn’t there to manage the crisis and guarantee their safety. One friend told me she did not think her daughter could walk freely and safely in the streets any more.“

The share of the population living in poverty (Lebanon hosts the highest number of refugees per capita of residents in the world, including more than 1 million Syrian refugees and 270,000 Palestinian refugees) has ballooned from 25 per cent in 2019 to 74 per cent this year.

The International Monetary Fund stands ready to hand over a $US11 billion bailout package on the condition Lebanon’s ruling elite enacts reforms. But the reforms would erode their power, making immediate change unlikely.

Some also question whether more money is the answer. Researchers from the London School of Economics have estimated $US170 billion in capital poured into Lebanon in the post-war period between 1993 and 2012, but much of the investment was leached away by corruption and mismanagement. Adjusted for inflation, that sum is greater than what was delivered through the Marshall Plan’s post-World War II reconstruction of Europe.

The only positive news for Lebanon’s immediate future is that few think the crisis will spiral into a new civil war. “The Lebanese consciousness has overcome a civil war notion,” says Wassef Habib al-Harakeh, a prominent lawyer and activist. “But these [leaders] are criminals, all of them. Their hands are soaked with blood.”

Harakeh was covered in his own blood last year after being attacked by four men in what he believes was an attempt to silence or even kill him.

“The present collapse — and it is not a crisis, it is a collapse — is not the result of technical issues,” he says. “It is a consequence of the system. And the permanence of the system means permanence of the collapse. To end this collapse, change in the system must take place.”

The scales of justice on a shelf behind his office desk are deliberately weighted towards one side as a reminder of what’s at stake in Lebanon over the coming weeks. “The balance should be leaning towards justice for the people, but the balance here is leaning towards oppression,” he says.

“Changing this is our battle.”

THE SYDNEY MORNING HERALD

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.