The mission has three scientific objectives: To study weather systems in the lower atmosphere, day and night through all martian seasons; to study how atmospheric oxygen and hydrogen escape into space; and to learn how processes in the lower atmosphere contribute to that escape.

By Bill Harwood

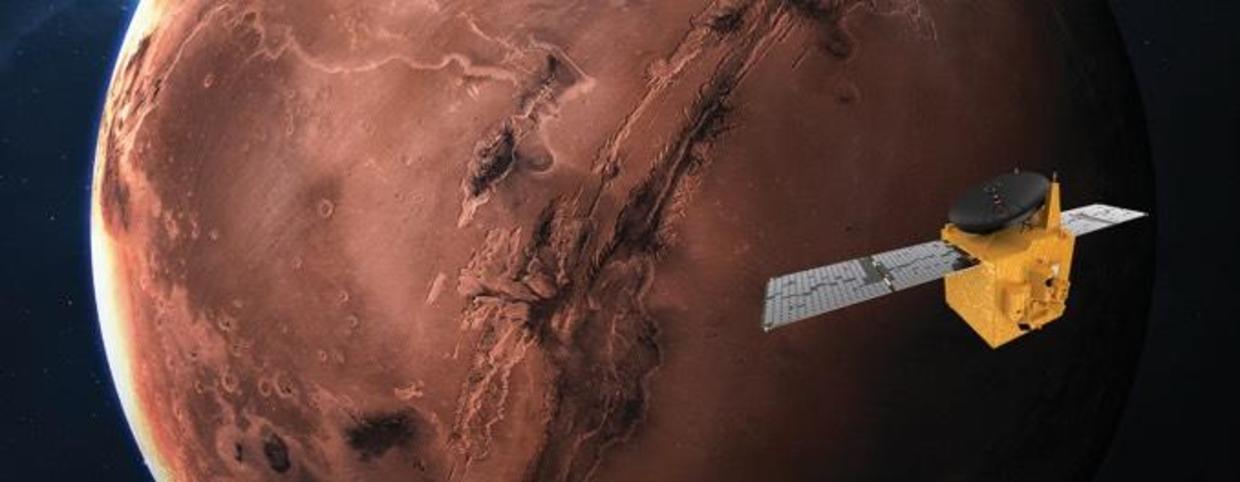

A Mars orbiter built by the United Arab Emirates in partnership with U.S. universities shot into space atop a Japanese H-2A rocket on Sunday, kicking off a seven-month voyage to the red planet. It is the first interplanetary mission attempted by an Arab nation and the first of three Mars missions scheduled for take off in the next two weeks.

The UAE’s $200 million “Hope” mission was designed with two major goals in mind: To study the martian atmosphere with three state-of-the-art instruments and to provide a “moonshot moment” for the youth of the Middle East, serving as inspiration to pursue careers in math and science.

“The objective was basically to use this mission to cause a disruptive change in the mindset of the youth, to create a research and development culture to support the creation of an innovative and creative and a competitive knowledge-based economy,” said Omran Sharaf, the Hope project manager.

“So it’s about the future of our economy. It’s about the post-oil economy. (UAE leadership) wanted to inspire the young generation to go into STEM and use this mission as a catalyst to cause disruptive change and shifts in multiple sectors. … That’s why they went with the Mars shot. (They) wanted to create an ecosystem that basically supports the creation of an advanced science and technology sector.”

Running five days late because of threatening weather, the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries H-2A rocket, equipped with two strap-on boosters for extra power, thundered to life at 5:58 p.m. EDT Sunday (6:58 a.m. Monday local time) and streaked away from a seaside firing stand at the picturesque Tanegashima Space Center.

The climb out of the dense lower atmosphere went smoothly and the rocket’s second stage reached its planned “parking orbit” 11-and-a-half minutes after launch. A second engine firing about 50 minutes later put the Mars probe on its seven-month trajectory to the red planet.

Flight controllers at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center in Dubai had a brief scare when initial telemetry indicated one of the probe’s two solar panels had not deployed, but a few minutes later they confirmed both arrays had, in fact, unfolded and subsystems were reported to be operating normally.

The mission is the first of three taking advantage of this year’s planetary launch window when Earth and Mars are in favorable positions to permit relatively quick transits.

China plans to launch its Tianwen-1 mission on July 23, sending an orbiter to Mars along with a sophisticated surface rover. One week later, NASA intends to launch its $2.4 billion Perseverance Mars rover to search for signs of past or present microbial life and to collect rock and soil samples for eventual return to Earth.

The European Space Agency had planned to launch its powerful ExoMars rover during the current launch window. But ESA was forced to stand down until the next window opens in 2022, primarily because of problems with the parachutes needed to help lower the rover to the martian surface.

Hope, Tianwen-1 and Perseverance will all reach Mars in February 2021. While Hope will slip into an elliptical orbit for at least two years of atmospheric research, Perseverance will descend directly to touchdown near an ancient river delta where water once flowed and where traces of past microbial activity might be present.

The Tianwen-1 rover will remain attached to the Chinese orbiter for several months before descending to touchdown on a broad plain known as Utopia Planitia, one of two proposed landing sites.

But the UAE was first off the pad. Assuming no problems develop, Hope will carry out a half-hour-long rocket firing next February, burning half its propellant to slow down enough to slip into an elliptical orbit with a high point of about 26,700 miles and a low point of around 12,400 miles.

The mission represents an ambitious bid to join the handful of nations that have attempted interplanetary exploration. The spacecraft was built in the United States by Emirates engineers working at the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado at Boulder, with participation by Arizona State University and the University of California at Berkeley.

Equipped with three science instruments — a high-resolution camera and two sophisticated spectrometers — Hope is designed to operate for at least one martian year, the equivalent of two years on Earth.

The mission has three scientific objectives: To study weather systems in the lower atmosphere, day and night through all martian seasons; to study how atmospheric oxygen and hydrogen escape into space; and to learn how processes in the lower atmosphere contribute to that escape.

The overall goal is to collect data that will complement other Mars missions, helping scientists figure out how Mars changed from a warm, wet world with an atmosphere thick enough to permit liquid water on the surface, to a dry, frigid world with an atmospheric pressure less than 1% of Earth’s.

NASA’s Maven orbiter has been studying the martian atmosphere for more than seven years. The Hope orbiter will collect complementary data, helping researchers fill in the blanks.

The Hope probe “was designed in order to answer questions that have been raised by previous missions,” said Bruce Jakosky, Maven’s principal investigator. “Our goal is to understand how the atmosphere works today and how the atmosphere has evolved through time.”

But the science is just part of the UAE’s message to the Middle East.

“We live in a place of turmoil, a place that is made up of 100 hundred million youth under the age of 35 that want to find opportunities to work,” deputy project manager Sarah Al Amiri, UAE minister of advanced sciences and chair of the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center, told CBS News in a pre-launch interview.

“And their talents at the time when we announced (Hope) were being used in the wrong groups, they were being used for terrorism and other forms of extremism by different groups in the region. And this mission was meant to provide a different way of working and a different way of forming opportunities for the region.”

And that, she said, is why the spacecraft was named Al Amal, or “Hope.”

Bill Harwood has been covering the U.S. space program full-time since 1984, first as Cape Canaveral bureau chief for United Press International and now as a consultant for CBS News. He covered 129 space shuttle missions, every interplanetary flight since Voyager 2’s flyby of Neptune and scores of commercial and military launches. Based at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Harwood is a devoted amateur astronomer and co-author of “Comm Check: The Final Flight of Shuttle Columbia.”

CBS

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.