By Mike Hixenbaugh

Dr. Arturo Casadevall was working from home in Baltimore on Thursday when his phone started to buzz with messages from colleagues. The commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration had just announced during a White House press briefing that the agency was investigating the possibility of using blood plasma donated by recovered coronavirus patients as a promising short-term treatment for the virus.

“There’s a cross-agency effort about something called convalescent plasma,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn said during the nationally televised briefing. “This is a pretty exciting area. And again, this is something that we have given assistance to other countries with as this crisis has developed, so FDA has been working for some time on this.”

Casadevall, an infectious disease expert at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, was surprised but pleased to hear of the agency’s interest. For weeks, he has led an ad hoc team of researchers from across the country who are working to establish a network of hospitals and blood banks that can begin collecting blood serum or plasma from coronavirus survivors, with the hopes of using it to treat critically ill patients and boost the immune systems of hospital workers.

The method — essentially harvesting virus-fighting antibodies from the blood of previously infected patients — dates back more than a century, but has not been used widely in the United States in decades. The treatment was associated with milder symptoms and shorter hospital stays for some patients during the 2002 SARS outbreak, and initial reports from China suggest convalescent plasma might also be effective in dulling the effects of COVID-19, the disease caused by the new coronavirus, though Hahn cautioned that more testing was needed.

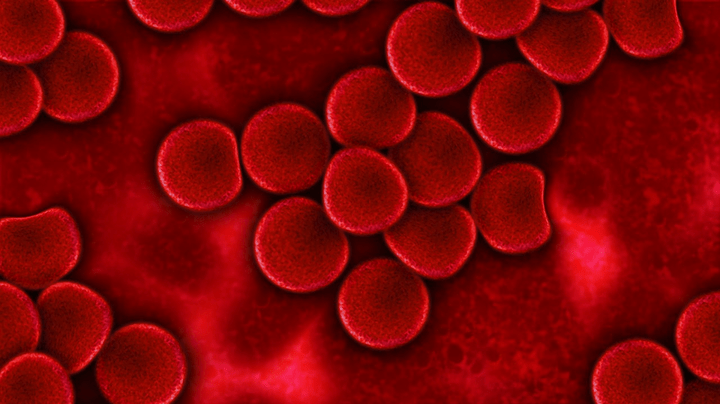

Patients tend to make large numbers of antibodies against an infecting pathogen, and these antibodies often circulate in the blood of survivors for months or years afterward. By collecting and transfusing a survivor’s serum or plasma — the liquid portion of blood left once cells and platelets have been removed — doctors could potentially boost an ailing patient’s immune response, Casadevall said.

The treatment is not without risks. There is danger in giving a patient the wrong type of blood or inadvertently transmitting other pathogens in a transfusion, but safety advancements over the past two decades have made adverse outcomes rare. Blood banks would also need to devise tests to detect whether donors have antibodies in their blood that kill the coronavirus, Casadevall said.

Doctors from nearly two dozen hospitals have joined the Johns Hopkins-led effort, he said, including researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, the Stanford University Medical Center in California and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

Casadevall has been among the treatment’s most vocal proponents. He argued in a Wall Street Journal op-ed and in an interview with NBC News last week that, while it might be months before there are antiviral drugs to treat the coronavirus, local blood banks could begin producing convalescent plasma in a matter of weeks. He said he hopes Hahn’s comments signal that the federal government will help coordinate and streamline their work.

In response to an interview request and written questions, an FDA spokesman directed a reporter to a press release issued Thursday. It said the FDA was committed to working with researchers and drugmakers “to expedite the development and availability of critical medical products to prevent and treat this novel virus,” including convalescent plasma.

Casadevall’s team submitted its initial application to begin testing the treatment to the FDA on Thursday. He hopes to clear regulatory hurdles in time to begin treating patients within the next four to six weeks.

“Until more effective drug treatments are ready, this might be our best option,” he said. “We’re working around the clock on this, dozens of us across the country, many of us working from our homes and through the weekends, because we don’t have time to spare.”

NBC

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.