Answering the most common questions about the COVID-19 pandemic, including the best protective measures and what’s next in battling the spread.

By Jackson Ryan

For the most up-to-date news and information about the coronavirus pandemic, visit the WHO website.

The COVID-19 outbreak, which began last December, has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. The respiratory illness, which is caused by a never-before-seen coronavirus, has spread across the world and claimed more than 6,500 lives in three months. The epicenter — Wuhan, China — experienced the worst of the initial outbreak but now large, secondary outbreaks have occurred across Europe and in Iran and South Korea.

The WHO was first alerted to the disease on New Year’s Eve, and in the following weeks researchers linked it to a family of viruses known as coronaviruses, the same family responsible for the diseases SARS and MERS, as well as some cases of the common cold. On March 11, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO director-general, announced the outbreak would be declared a pandemic, the first time a coronavirus has caused such a spread.

The situation continues to evolve as more information becomes available. We’ve collated everything we know about the novel virus, what’s next for researchers and some of the steps you can take to reduce your risk.

- What is a coronavirus?

- What is COVID-19?

- What is a pandemic?

- Where did the virus come from?

- How many confirmed cases and deaths have been reported?

- What is the fatality rate of COVID-19?

- How do we know it’s a new coronavirus?

- How is coronavirus spread?

- Can I get coronavirus from a package?

- What are the symptoms of the coronavirus?

- How infectious is the coronavirus?

- Should you make your own hand sanitizer?

- Is there a treatment for the coronavirus?

- Is there a vaccine for coronavirus?

- How to reduce your risk of the coronavirus

What is a coronavirus?

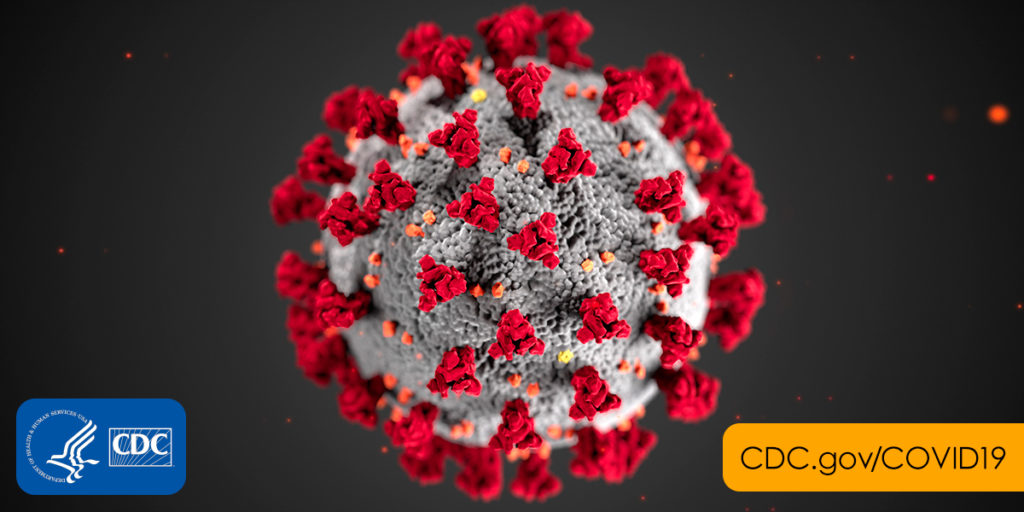

Coronaviruses belong to a family known as Coronaviridae, and under an electron microscope they look like spiked rings. They’re named for these spikes, which form a halo or “crown” (corona is Latin for crown) around their viral envelope.

Coronaviruses contain a single strand of RNA (as opposed to DNA, which is double-stranded) within the envelope and, as a virus, can’t reproduce without getting inside living cells and hijacking their machinery. The spikes on the viral envelope help coronaviruses bind to cells, which gives them a way in, like blasting a door open with C4. Once inside, they turn the cell into a virus factory — the RNA and some enzymes use the cell’s molecular machinery to produce more viruses, which are then shipped out of the cell to infect other cells. Thus, the cycle starts anew.

Typically, these types of viruses are found in animals ranging from livestock and household pets to wildlife such as bats. Some are responsible for disease, like the common cold. When they make the jump to humans, they can cause fever, respiratory illness and inflammation in the lungs. In immunocompromised individuals, such as the elderly or those with HIV-AIDS, such viruses can cause severe respiratory illness, resulting in pneumonia and even death.

Extremely pathogenic coronaviruses were behind the diseases SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) and MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) in the last two decades. These viruses were easily transmitted from human to human but were suspected to have passed through different animal intermediaries: SARS was traced to civet cats and MERS to dromedary camels. SARS, which showed up in the early 2000s, infected more than 8,000 people and resulted in nearly 800 deaths. MERS, which appeared in the early 2010s, infected almost 2,500 people and led to more than 850 deaths.

What is COVID-19?

In the early days of the outbreak, the media, medical experts and health professionals were referring to “the coronavirus” as a catch-all term to discuss the outbreak of illness. But a coronavirus is a type of virus as we explain in the section above, rather than a disease itself.

To alleviate the confusion and streamline reporting, WHO has named the new disease COVID-19 (for coronavirus disease 2019). “Having a name matters to prevent the use of other names that can be inaccurate or stigmatizing,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO. “It also gives us a standard format to use for any future coronavirus outbreaks.”

The Coronavirus Study Group, part of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, was responsible for naming the novel coronavirus itself. The novel coronavirus — the one that causes the disease — is known as SARS-CoV-2. The group “formally recognizes this virus as a sister to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses (SARS-CoVs),” the species responsible for the SARS outbreak in 2002-2003.

Therefore:

- The novel coronavirus is officially named SARS-CoV-2.

- The disease caused by SARS-CoV-2 is officially named COVID-19.

What is a pandemic?

On March 11, the WHO officially classified the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.

“Pandemic is not a word to use lightly or carelessly. It is a word that, if misused, can cause unreasonable fear, or unjustified acceptance that the fight is over, leading to unnecessary suffering and death,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO director-general, at a press briefing.

So what is a pandemic?

Both the CDC and the WHO have different definitions, and if you look in a dictionary, you may find something different again. In the simplest terms, a pandemic can be defined as “a worldwide outbreak of a new disease.”

The “new” is key here, because many diseases persist in the population and spread each year. For example, influenza (the flu) infects a lot of people every year and can be found across the world. Unlike COVID-19, it’s been circulating in the community for many years, there’s some natural immunity to it, and we know so much about it we can protect against it.

What does this all mean? Well, nothing in your day-to-day life should change. The COVID-19 virus itself hasn’t changed. It hasn’t become more dangerous and hasn’t mutated to infect people more quickly. And the risk of being infected doesn’t exponentially increase now that the word pandemic is being used.

Where did the virus come from?

The virus appears to have originated in Wuhan, a Chinese city about 650 miles south of Beijing that has a population of more than 11 million people. The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, which sells fish, as well as a panoply of meat from other animals, including bats, snakes and pangolins, was implicated in the spread in early January.

Prestigious medical journal The Lancet published an extensive summary of the clinical features of patients infected with the disease stretching back to Dec. 1, 2019. The very first patient identified had not been exposed to the market, suggesting the virus may have originated elsewhere and been transported to the market, where it was able to thrive or jump from human to animal and back again. Chinese authorities shut down the market on Jan. 1.

On Feb. 22, a report by the Global Times, a Chinese state media publication, suggested the Huanan seafood market was not the birthplace of the disease citing a Chinese study published on an open-access server in China.

Markets have been implicated in the origin and spread of viral diseases in past epidemics, including SARS and MERS. A large majority of the people so far confirmed to have come down with the new coronavirus had been to the Huanan Seafood marketplace in recent weeks. The market appears to be an integral piece of the puzzle, but research into the likely origin and connecting a “patient zero” to the initial spread is ongoing.

An early report, published in the Journal of Medical Virology on Jan. 22, suggested snakes were the most probable wildlife animal reservoir for SARS-CoV-2, but the work was soundly refuted by two further studies just a day later, on Jan. 23. “We haven’t seen evidence ample enough to suggest a snake reservoir for Wuhan coronavirus,” said Peter Daszak, president of nonprofit EcoHealth Alliance, which researches the links between human and animal health.

“This work is really interesting, but when we compare the genetic sequence of this new virus with all other known coronaviruses, all of its closest relatives have origins in mammals, specifically bats. Therefore, without further details on testing of animals in the markets, it looks like we are no closer to knowing this virus’ natural reservoir.”

Another group of Chinese scientists uploaded a paper to preprint website biorXiv, having studied the viral genetic code and compared it to the previous SARS coronavirus and other bat coronaviruses. They discovered the genetic similarities run deep: The virus shares 80% of its genes with the previous SARS virus and 96% of its genes with bat coronaviruses. Importantly, the study also demonstrated the virus can get into and hijack cells the same way SARS did.

The ant-eating pangolin, a small, scaly mammal, has also been implicated in the spread of SARS-CoV-2. According to the New York Times, it may be one of the most trafficked animals in the world and it was sold at the Huanan Seafood Market. The virus likely originated in bats but may have been able to hide out in the pangolin, before spreading from that animal to humans. Researchers caution the full data have not yet been published but coronaviruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 have been found in pangolins before.

All good science builds off previous discoveries — and there is still more to learn about the basic biology of SARS-CoV-2 before we have a good grasp of exactly which animal vector is responsible for transmission — but early indications are the virus is similar to those seen in bats and likely originated from them.

How many confirmed cases and deaths have been reported?

The virus has spread to over 50 countries since its discovery in late 2019 and the number of cases and deaths have been steadily rising since early January. The best way to keep track of the spread of the virus across the globe is this handy online tool, which is collating data from a number of sources including the CDC, the WHO and Chinese health professionals and is maintained by Johns Hopkins University.

The bulk of the confirmed cases and deaths have been recorded in China’s Hubei province where the outbreak originated. However, secondary outbreaks have been seen in South Korea, Italy and Iran and a cruise ship, the Diamond Princess, was quarantined in the Japanese port of Yokohama for 14 days in February due to an outbreak onboard. In total, 705 people on the ship were found to be infected with the coronavirus.

What is the fatality rate?

One of the most pressing questions for many is “how many people who get COVID-19 actually die from it?” — and that’s also a tough question to answer. Getting an accurate fatality rate is important for policy makers and health experts to control and counter outbreaks but determining the rate is quite complex.

Early estimates, from the WHO, put the rate above 3% based on the number of deaths in comparison to the number of cases.

“Globally, about 3.4% of reported COVID-19 cases have died,” said WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus during a press conference on March 3. “By comparison, seasonal flu generally kills far fewer than 1% of those infected.” However, experts are unconvinced, because limited testing across the world, along with the mild symptoms that many infected experience suggests there may be many people currently undiagnosed with COVID-19 and this would push the fatality rate lower. On the other hand, if deaths are under-reported, perhaps 3% is conservative.

COVID-19 also seems to affect older generations much more severely. A great piece at STAT news breaks down the demographics of the disease and which groups seem particularly at risk.

The bottom line: When looking for how deadly COVID-19 might be, a single number like 3.4% doesn’t tell the whole story — it’s much more complex than that. The fatality rate will change over time but the elderly (older than 60) and those with underlying health conditions, like cardiovascular disease and diabetes, are at higher risk.

How do we know it’s a new coronavirus?

The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention dispatched a team of scientists to Wuhan to gather information about the new disease and perform testing in patients, hoping to isolate the virus. Their work, published in the New England Journal of Medicine on Jan. 24, examined samples from three patients. Using an electron microscope, which can resolve images of cells and their internal mechanics, and studying the genetic code, the team were able to visualize and genetically identify the novel coronavirus.

Understanding the genetic code helps researchers in two ways: It allows them to create tests that can identify the virus from patient samples, and it gives them potential insight into creating treatments or vaccines.

The Peter Doherty Institute in Melbourne, Australia, was able to identify and grow the virus in a lab from a patient sample. They announced their discovery on Jan. 28. This is seen as one of the major breakthroughs in developing a vaccine and provides laboratories with the capability to both assess and provide expert information to health authorities and detect the virus in patients suspected of harboring the disease.

How does the coronavirus spread?

This is one of the major questions researchers are still working hard to answer. The first infections were potentially the result of animal-to-human transmission, but confirmation that human-to-human transmission was obtained in late January. As the virus has spread, local transmission has been seen across the world. Some of the most at-risk people are those that work in healthcare.

“The major concern is hospital outbreaks, which were seen with SARS and MERS coronaviruses,” said Raina MacIntyre, a professor of global biosecurity at the University of New South Wales, Australia. “Meticulous triage and infection control is needed to prevent these outbreaks and protect health workers.”

WHO says the virus can move from person to person via:

- Respiratory droplets — when a person sneezes or coughs.

- Direct contact with infected individuals.

- Contact with contaminated surfaces and objects.

A handful of viruses, including MERS, can survive for periods in the air after being sneezed or coughed from an infected individual. Although recent reports suggest the novel coronavirus may be transmitted in this way, the Chinese Center for Diseases Control and Prevention have reiterated there is no evidence for this. Writing in The Conversation on Feb. 14, virologists Ian Mackay and Katherine Arden explain “no infectious virus has been recovered from captured air samples.”

How long can the coronavirus survive on surfaces?

There’s still a lot to learn about the hardiness of this particular virus, but similar members of the coronavirus family have been explored in detail, including the coronaviruses responsible for the SARS and MERS outbreaks. Particularly notable is an article published on Feb. 6 in The Journal of Hospital Infection, which looked at a host of previous studies (22 in total) and found coronaviruses may persist on surfaces for up to nine days.

A chief concern for the public has been whether global package shipments could help spread the virus. Different materials can keep the virus alive for longer outside the body, but a range of factors needs to be taken into account when evaluating virus survival. The CDC is still investigating this but has come up with numbers for certain surfaces.

“On copper and steel it’s pretty typical, it’s pretty much about two hours,” Robert Redfield, director of the CDC, told US lawmakers on Feb. 27, according to a report by Reuters. “But I will say on other surfaces — cardboard or plastic — it’s longer, and so we are looking at this.”

The CDC will continue to investigate but believes the risk of contracting coronavirus from packages is still low. The WHO notes it is “very unlikely” you would see the coronavirus persist after being moved, traveled and exposed to different conditions. Best tip? Wash your hands!

What are the symptoms?

The new coronavirus causes symptoms similar to those of previously identified disease-causing coronaviruses. In currently identified patients, there seems to be a spectrum of illness: A large number experience mild pneumonia-like symptoms, while others have a much more severe response.

On Jan. 24, prestigious medical journal The Lancet published an extensive analysis of the clinical features of the disease.

According to the report, patients present with:

- Fever, elevated body temperature

- Dry cough

- Fatigue or muscle pain

- Breathing difficulties

Less common symptoms include:

- Coughing up mucus or blood

- Headaches

- Diarrhea

- Kidney failure

As the disease progresses, patients also come down with pneumonia, which inflames the lungs and causes them to fill with fluid. This can be detected by an X-ray.

How infectious is the coronavirus?

A widely shared Twitter thread by Eric Feigl-Ding, a Harvard University epidemiologist, suggested the new coronavirus is “thermonuclear pandemic level bad” based on a metric known as the “r nought” (R0) value. This metric helps determine the basic reproduction number of an infectious disease. In the simplest terms, the value relates to how many people can be infected by one person carrying the disease. It was widely criticized before being deleted.

Infectious diseases such as measles have an R0 of 12 to 18, which is remarkably high. The SARS epidemic of 2002-2003 had an R0 of around 3. A handful of studies modeling the COVID-19 outbreak have given a similar value with a range between 1.4 and 3.8. However, there is plenty of variation between studies and models attempting to predict the R0 of novel coronavirus due to the constantly changing number of cases. It seems to have settled on a figure around 2.2.

In the early stages of understanding the disease and its spread, it should be stressed these studies are informative, but they aren’t definitive. They give an indication of the potential for the disease to move from person-to-person, but we still don’t have enough information about how the new virus spreads.

“Some experts are saying it is the most infectious virus ever seen — that is not correct,” MacIntyre said. “If it was highly infectious (more infectious than influenza as suggested by some) we should have seen hundreds, if not thousands of cases outside of China by now, given Wuhan is a major travel hub.”

China has suggested the virus can spread before symptoms present. Writing in The Conversation on Jan. 28, MacIntyre noted there was no evidence for these claims so far but does suggest children and young people could be infectious without displaying any symptoms. This also makes airport screening less impactful, because harboring the disease but showing no signs could allow it to insidiously spread further.

Should you make your own hand sanitizer?

As unnecessary panic surrounding the spread of the coronavirus has gripped consumers, the shelves have emptied. In Australia, shoppers have raced out to buy up whatever they can: toilet paper, acetaminophen (also know as paracetamol), pasta and, of course, hand sanitizer. As CNET Wellness editor Sarah Mitroff reports, most places in the US are also sold out of the latter, as are many online stores.

That’s led to widespread reports that it’s a good idea to make your own hand sanitizer — but experts warn that you risk making a sanitizer that either isn’t effective or is way too harsh.

In CNET’s guide to DIY hand sanitizer, we also rule out using hard liquor. Recipes that call for vodka or spirits should be avoided entirely, because you need a high proof liquor to get the right concentration of alcohol by volume. That’s because most liquor is mixed with water, so if you mix an 80-proof vodka (which is the standard proof) with aloe, you’ll have hand sanitizer that contains roughly only 40% alcohol.

The alternative is to wash your hands. As the CDC and WHO continue to suggest, washing your hands with soap and water for around 20 seconds is one of the best ways to protect yourself from getting sick right now. You should also avoid touching your face if you can, as the virus can be transferred into the body if you’ve been in contact with someone who’s infected.

Is there a treatment for the coronavirus?

Coronaviruses are hardy organisms. They’re effective at hiding from the human immune system, and we haven’t developed any reliable treatments or vaccines to eradicate them. In most cases, health officials attempt to deal with the symptoms.

“There is no recognized therapeutic against coronaviruses,” said Mike Ryan, executive director of the WHO Health Emergencies Programme, during a press conference on Jan. 29. “The primary objective in an outbreak related to a coronavirus is to give adequate support of care to patients, particularly in terms of respiratory support and multiorgan support.”

Notably, because they are viruses, coronaviruses are not susceptible to antibiotics. Antibiotics are medicines designed to fight bacteria and do not do any damage to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. There are no specific treatments for COVID-19 as yet, though a number are in the works including experimental antivirals, which can attack the virus, and existing drugs targeted at other viruses like HIV which have shown some promise.

Is there a vaccine for coronavirus?

Developing new vaccines takes time and they must be rigorously tested and confirmed safe via clinical trials before they can be routinely used in humans. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in the US, has commonly stated a vaccine is at least a year to 18 months away. Experts agree there’s a ways to go yet.

However, there is great progress being made in this regard and a number of vaccine candidates have appeared in the time since COVID-19 was discovered. We’ve collated everything we know about potential vaccines and current treatment options that are being used around the world.

In developing a vaccine that targets SARS-CoV-2, scientists are looking at the spike proteins intensely. These proteins, which are present on the surface of the virus, enable it to enter human cells where it can replicate and make copies of itself. Researchers have been able to map the projections in 3D and research suggests they could be a viable antigen — a fragment that stimulates the human body’s immune system — in any potential coronavirus vaccine.

The protein is prevalent in coronaviruses we’ve battled in the past, too — including the one that caused the SARS outbreak in China in 2002-2003. This has given researchers a head start on building vaccines against part of the spike protein and, using animal models, they have already demonstrated an immune response.

Notably, SARS, which infected around 8,000 people and killed around 800, seemed to run its course and then mostly disappear. It wasn’t a vaccine that turned the tide on the disease but rather effective communication between nations and a range of tools that helped track the disease and its spread.

“We learnt that epidemics can be controlled without drugs or vaccines, using enhanced surveillance, case isolation, contact tracking, PPE and infection control measures,” MacIntyre said.

How to reduce your risk of coronavirus

With confirmed cases now seen across the globe, it’s possible that SARS-CoV-2 may spread much further afield than China. The WHO recommends a range of measures to protect yourself from contracting the disease, based on good hand hygiene and good respiratory hygiene — in much the same way you’d reduce the risk of contracting the flu. The novel coronavirus does spread and infect humans slightly differently to the flu, but because it predominantly affects the respiratory tract, the protection measures are similar.

Meanwhile, the US State Department on Jan. 30 issued a travel advisory with a blunt message: “Do not travel to China.” An earlier warning from the CDC advised people to “avoid nonessential travel.”

A Twitter thread, developed by the WHO, is below.

Q: What are the symptoms of #coronavirus infection?

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) January 17, 2020

A: It depends on the virus, but common signs incl. respiratory symptoms, fever, cough, shortness of breath & breathing difficulties. In more severe cases, it can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, etc pic.twitter.com/EGbXcZnkYy

You may also be considering buying a face mask to protect yourself from contracting the virus. You’re not alone — stocks of face masks have been selling out across the world, with Amazon and Walmart.com experiencing shortages. Reporting from Sydney in January, I found lines at the pharmacy extending down the street.

On Feb. 29, US Surgeon General Jerome Adams issued a plea on Twitter for people to stop indiscriminately snapping up masks. “Seriously people- STOP BUYING MASKS!” the tweet said. “They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!”

Seriously people- STOP BUYING MASKS!

— U.S. Surgeon General (@Surgeon_General) February 29, 2020

They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but if healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts them and our communities at risk!

https://t.co/UxZRwxxKL9

The surgeon general’s tweet points to online guidance from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The CDC says it doesn’t advise healthy members of the public to wear face masks to guard against COVID-19 and other respiratory diseases. Who should wear them, according to the agency? “Facemasks should be used by people who show symptoms of COVID-19 to help prevent the spread of the disease to others,” says the CDC’s page on COVID-19 treatment and prevention. “The use of facemasks is also crucial for health workers and people who are taking care of someone in close settings (at home or in a health care facility).” CNET’s Wellness team has a story up with more details about face masks.

How to stay informed

As the virus continues to spread, it’s easy to get caught up in the fear and alarmism rampantly escalating through social media. There’s misinformation and disinformation swirling about the effects of the disease, where it’s spreading and how. Experts still caution that the virus appears to be mild, especially in comparison with infections by other viruses, such as influenza or measles, and has a markedly lower death rate than previous coronavirus outbreaks.

CNET

UPDATE AS OF MARCH 15 ON NUMBER OF CASES AND DEATHS

Confirmed Cases and Deaths by Country, Territory, or Conveyance

The coronavirus COVID-19 is affecting 162 countries and territories around the world and 1 international conveyance (the Diamond Princess cruise ship harbored in Yokohama, Japan). The day is reset after midnight GMT+0. The “New” columns for China display the previous day changes (as China reports after the day is over). For all other countries, the “New” columns display the changes for the current day while still in progress.

Report coronavirus casesSearch:

| Country, Other | Total Cases | New Cases | Total Deaths | New Deaths | Total Recovered | Active Cases | Serious, Critical | Tot Cases/ 1M pop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 80,880 | +36 | 3,213 | +14 | 67,819 | 9,848 | 3,226 | 56.2 |

| Italy | 24,747 | 1,809 | 2,335 | 20,603 | 1,672 | 409.3 | ||

| Iran | 14,991 | +1,053 | 853 | +129 | 4,590 | 9,548 | 178.5 | |

| Spain | 9,428 | +1,440 | 335 | +41 | 530 | 8,563 | 272 | 201.6 |

| S. Korea | 8,236 | +74 | 75 | 1,137 | 7,024 | 59 | 160.6 | |

| Germany | 6,924 | +1,111 | 14 | +1 | 59 | 6,851 | 2 | 82.6 |

| France | 5,423 | 127 | 12 | 5,284 | 400 | 83.1 | ||

| USA | 4,046 | +366 | 71 | +3 | 73 | 3,902 | 12 | 12.2 |

| Switzerland | 2,221 | +4 | 18 | +4 | 4 | 2,199 | 256.6 | |

| UK | 1,543 | +152 | 36 | +1 | 20 | 1,487 | 20 | 22.7 |

| Netherlands | 1,413 | +278 | 24 | +4 | 2 | 1,387 | 45 | 82.5 |

| Norway | 1,312 | +56 | 3 | 1 | 1,308 | 27 | 242.0 | |

| Sweden | 1,103 | +63 | 7 | +4 | 1 | 1,095 | 2 | 109.2 |

| Belgium | 1,058 | +172 | 5 | +1 | 1 | 1,052 | 33 | 91.3 |

| Austria | 1,018 | +158 | 3 | +2 | 8 | 1,007 | 12 | 113.0 |

| Denmark | 914 | +50 | 4 | +2 | 1 | 909 | 10 | 157.8 |

| Japan | 845 | +6 | 27 | +3 | 144 | 674 | 36 | 6.7 |

| Diamond Princess | 696 | 7 | 456 | 233 | 15 | |||

| Malaysia | 566 | +138 | 42 | 524 | 9 | 17.5 | ||

| Qatar | 439 | +38 | 4 | 435 | 152.4 | |||

| Australia | 375 | +75 | 5 | 27 | 343 | 1 | 14.7 | |

| Canada | 375 | +34 | 1 | 11 | 363 | 1 | 9.9 | |

| Greece | 352 | +21 | 4 | 8 | 340 | 5 | 33.8 | |

| Portugal | 331 | +86 | 3 | 328 | 9 | 32.5 | ||

| Czechia | 298 | +5 | 298 | 2 | 27.8 | |||

| Finland | 278 | +34 | 10 | 268 | 1 | 50.2 | ||

| Israel | 255 | +42 | 4 | 251 | 4 | 29.5 | ||

| Slovenia | 253 | +34 | 1 | 252 | 3 | 121.7 | ||

| Singapore | 243 | +17 | 109 | 134 | 11 | 41.5 | ||

| Bahrain | 221 | +7 | 1 | +1 | 77 | 143 | 1 | 129.9 |

| Estonia | 205 | +34 | 1 | 204 | 154.5 | |||

| Brazil | 203 | +3 | 2 | 201 | 2 | 1.0 | ||

| Iceland | 180 | 180 | 1 | |||||

| Ireland | 170 | 2 | 5 | 163 | 6 | 34.4 | ||

| Romania | 158 | +19 | 9 | 149 | 1 | 8.2 | ||

| Poland | 156 | +31 | 3 | 153 | 3 | 4.1 | ||

| Hong Kong | 155 | +6 | 4 | 81 | 70 | 4 | 20.7 | |

| Chile | 155 | +80 | 155 | 8.1 | ||||

| Egypt | 150 | +24 | 2 | 32 | 116 | 1.5 | ||

| Thailand | 147 | +33 | 1 | 35 | 111 | 1 | 2.1 | |

| Philippines | 142 | +2 | 12 | 5 | 125 | 1 | 1.3 | |

| Pakistan | 136 | +83 | 2 | 134 | 0.6 | |||

| Indonesia | 134 | +17 | 5 | 8 | 121 | 0.5 | ||

| India | 129 | +15 | 2 | 13 | 114 | 0.1 | ||

| Iraq | 124 | 10 | 26 | 88 | 3.1 | |||

| Kuwait | 123 | +11 | 9 | 114 | 4 | 28.8 | ||

| Saudi Arabia | 118 | 6 | 112 | 3.4 | ||||

| San Marino | 109 | 7 | 4 | 98 | 11 | |||

| Lebanon | 109 | 3 | 1 | 105 | 3 | 16.0 | ||

| UAE | 98 | 23 | 75 | 2 | 9.9 | |||

| Russia | 93 | +30 | 8 | 85 | 0.6 | |||

| Peru | 86 | +15 | 1 | 85 | 8 | 2.6 | ||

| Luxembourg | 81 | +4 | 1 | 80 | 10 | |||

| Slovakia | 72 | +11 | 72 | 13.2 | ||||

| Taiwan | 67 | +8 | 1 | 20 | 46 | 2.8 | ||

| South Africa | 64 | +3 | 64 | 1.1 | ||||

| Bulgaria | 62 | +11 | 2 | 60 | 8.9 | |||

| Vietnam | 61 | +4 | 16 | 45 | 0.6 | |||

| Croatia | 57 | +8 | 3 | 54 | 13.9 | |||

| Argentina | 56 | 2 | 3 | 51 | 1 | 1.2 | ||

| Panama | 55 | 1 | 54 | 12.7 | ||||

| Serbia | 55 | +7 | 1 | 54 | 2 | 6.3 | ||

| Algeria | 54 | 4 | 10 | 40 | 1.2 | |||

| Brunei | 54 | +4 | 54 | 1 | ||||

| Colombia | 54 | +20 | 1 | 53 | 1.1 | |||

| Mexico | 53 | +10 | 4 | 49 | 1 | 0.4 | ||

| Albania | 51 | +9 | 1 | 50 | 2 | 17.7 | ||

| Hungary | 39 | +7 | 1 | 1 | 37 | 4.0 | ||

| Palestine | 39 | +1 | 39 | 7.6 | ||||

| Ecuador | 37 | 2 | 35 | 1 | 2.1 | |||

| Belarus | 36 | +9 | 3 | 33 | 3.8 | |||

| Costa Rica | 35 | 35 | 3 | 6.9 | ||||

| Latvia | 34 | +4 | 1 | 33 | 18.0 | |||

| Georgia | 33 | 1 | 32 | 1 | 8.3 | |||

| Cyprus | 33 | 33 | 1 | 27.3 | ||||

| Armenia | 30 | +2 | 1 | 29 | 2 | 10.1 | ||

| Malta | 30 | +9 | 2 | 28 | ||||

| Morocco | 29 | +1 | 1 | 1 | 27 | 1 | 0.8 | |

| Sri Lanka | 28 | +10 | 1 | 27 | 1.3 | |||

| Azerbaijan | 25 | +2 | 1 | 6 | 18 | 2.5 | ||

| Senegal | 24 | 2 | 22 | 1.4 | ||||

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 24 | 24 | 7.3 | |||||

| Moldova | 23 | 23 | 1 | 5.7 | ||||

| Oman | 22 | 9 | 13 | 4.3 | ||||

| Afghanistan | 21 | +5 | 1 | 20 | 0.5 | |||

| Tunisia | 20 | 20 | 2 | 1.7 | ||||

| Jordan | 19 | +7 | 1 | 18 | 1.9 | |||

| North Macedonia | 19 | 1 | 18 | 9.1 | ||||

| Faeroe Islands | 18 | +7 | 18 | |||||

| Turkey | 18 | 18 | 0.2 | |||||

| Lithuania | 17 | +3 | 1 | 16 | 6.2 | |||

| Venezuela | 17 | 17 | 0.6 | |||||

| Burkina Faso | 15 | +12 | 15 | 0.7 | ||||

| Jamaica | 15 | +5 | 2 | 13 | 5.1 | |||

| Martinique | 15 | +5 | 15 | |||||

| Andorra | 14 | +9 | 14 | |||||

| Maldives | 13 | 13 | ||||||

| Cambodia | 12 | 1 | 11 | 0.7 | ||||

| Macao | 11 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| Dominican Republic | 11 | 11 | 1.0 | |||||

| Bolivia | 11 | +1 | 11 | 0.9 | ||||

| French Guiana | 11 | +4 | 11 | |||||

| Kazakhstan | 10 | +1 | 10 | 0.5 | ||||

| Réunion | 9 | +2 | 9 | |||||

| New Zealand | 8 | 8 | 1.7 | |||||

| Bangladesh | 8 | +3 | 3 | 5 | ||||

| Paraguay | 8 | 8 | 1 | 1.1 | ||||

| Uruguay | 8 | +2 | 8 | 2.3 | ||||

| Uzbekistan | 8 | +4 | 8 | 0.2 | ||||

| Guyana | 7 | +3 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Liechtenstein | 7 | 7 | ||||||

| Monaco | 6 | +4 | 6 | |||||

| Channel Islands | 6 | +3 | 6 | |||||

| Ghana | 6 | 6 | 0.2 | |||||

| Guadeloupe | 6 | +1 | 6 | |||||

| Honduras | 6 | +3 | 6 | 0.6 | ||||

| Ukraine | 5 | +2 | 1 | 4 | 0.1 | |||

| Ethiopia | 5 | +1 | 5 | |||||

| Puerto Rico | 5 | 5 | 1.7 | |||||

| Rwanda | 5 | 5 | 0.4 | |||||

| Cameroon | 4 | 4 | 0.2 | |||||

| Ivory Coast | 4 | 4 | 0.2 | |||||

| Cuba | 4 | 4 | 0.4 | |||||

| Trinidad and Tobago | 4 | +2 | 4 | 2.9 | ||||

| French Polynesia | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Guam | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Kenya | 3 | 3 | 0.1 | |||||

| St. Barth | 3 | +2 | 3 | |||||

| Seychelles | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| Guatemala | 2 | +1 | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | |||

| Nigeria | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Aruba | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Curaçao | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| DRC | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Namibia | 2 | 2 | 0.8 | |||||

| Saint Lucia | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Saint Martin | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Cayman Islands | 1 | 1 | +1 | 0 | ||||

| Sudan | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Nepal | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Bahamas | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Benin | 1 | +1 | 1 | 0.1 | ||||

| Bhutan | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| CAR | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | |||||

| Congo | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | |||||

| Equatorial Guinea | 1 | 1 | 0.7 | |||||

| Gabon | 1 | 1 | 0.4 | |||||

| Gibraltar | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| Greenland | 1 | +1 | 1 | |||||

| Guinea | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| Vatican City | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Liberia | 1 | +1 | 1 | 0.2 | ||||

| Mauritania | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | |||||

| Mayotte | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Mongolia | 1 | 1 | 0.3 | |||||

| St. Vincent Grenadines | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Somalia | 1 | +1 | 1 | 0.1 | ||||

| Suriname | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Eswatini | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | |||||

| Tanzania | 1 | +1 | 1 | |||||

| Togo | 1 | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| U.S. Virgin Islands | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Total: | 175,754 | 6,194 | 6,716 | 211 | 77,868 | 91,170 | 5,967 | 22.5 |

Highlighted in green= all cases have recovered from the infection Highlighted in grey= all cases have had an outcome (there are no active cases) The “New” columns for China display the previous day changes (as China reports after the day is over). For all other countries, the “New” columns display the changes for the current day while still in progress.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.