By Mat Nashed

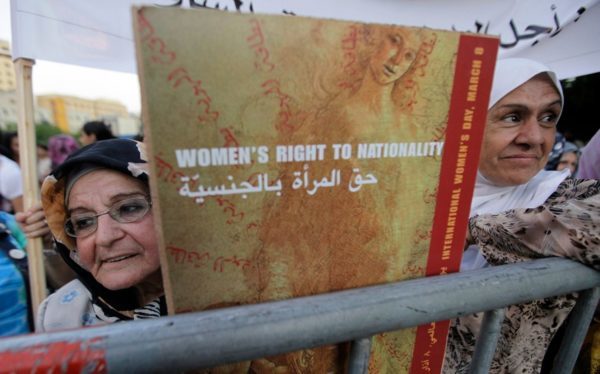

There are roughly 80,000 stateless people in Lebanon. They shouldn’t be confused with Syrian refugees born without papers or Palestinians who still don’t have a country. These are the children and husbands of Lebanese women barred by law from passing citizenship to their families. Invisible to the state, they cannot get government benefits or participate in public life, and many live in informal settlements.

Across the Middle East, nationality is foremost an expression of the status and privileges of men, but the consensus is gradually changing thanks to women like Lina Abou Habib. She recalls visiting the Moroccan capital of Rabat in 2000, where she met several Arab feminists from six other countries that all prohibited women from conferring citizenship to their spouse or children. During the conference, those women vowed to lobby for inclusive citizenship laws. Starting with Egypt in 2004, nations from North Africa to the Gulf adopted partial reforms. But in Habib’s home of Lebanon, nothing changed.

“Maybe I was too naive,” says Habib, 57. “I thought Lebanon would be one of the easiest cases, but the process turned out to be way more vicious.”

With the tide finally starting to turn nearly two decades later, Habib is leading the fight.

Born into a Christian family, Habib rebelled against conservative religious teachings in her Catholic school. Her upbringing, she says, naturally guided her toward feminism. But nothing shaped Habib or her country like the Lebanese civil war (1975–1990). After witnessing horrific crimes committed in the name of religion, she concluded that Lebanon’s sectarian system was rotten to the core.

Lebanon’s paternal nationality laws are rooted in that system. With the country of 6 million hosting more than a million Sunni Muslim refugees — Palestinians and Syrians— Christian and Shiite politicians fear that many could be naturalized if women can transfer citizenship to their spouse or children. It’s a scenario that critics believe would tip the country’s delicate sectarian balance in favor of Sunnis. But Habib doesn’t buy the argument. As the co-founder and chair of the Collective for Research and Training on Development — Action (CRTDA), a local feminist organization, she and her colleagues remain headstrong in campaigning for equal citizenship rights.

The issue has recently gained more traction. Just last year, President Michel Aoun sparked outrage when he granted citizenship to 375 people through a secret decree. Numerous critics smelled bribery.

Whatever the truth, Aoun’s actions were hypocritical, as he has fought against reforming the nationality law in the past. Nowadays his son-in-law, Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil, is the most vocal critic in the family. Although Bassil says he supports reform, he has stood against giving Lebanese women the right to confer nationality to Palestinians or Syrians.

“The arguments against reform are always xenophobic,” says Habib. “But it’s not a right if some women have it and others don’t. All women must have it.”

On the surface, the Aoun family isn’t united. Aoun’s daughter Claudine, the head of the National Commission for Lebanese Women, has used her political clout to push Parliament — and her father — to change the nationality law. But Claudine’s proposal falls short of enshrining gender equality.

For starters, the draft law states that women can give nationality only to children under the age of 18 and not to their spouses. Children would be able to obtain a green residency card, which they would hold for five years before applying for citizenship. “Everyone was saying that Claudine’s idea was so wonderful, but from the start, we at CRTDA said that her proposal was creating new layers of discrimination,” Habib says.

Karima Chebbo, another member of CRTDA, says Habib has grown stronger over the years due to arguing with political elites. “She never compromises,” Chebbo says. “She also never makes a cause or campaign about herself.”

That much is clear from Habib’s reluctance to talk about her personal life. All she shares is that she has a daughter who recently graduated from university and four cats. Her core belief, she stresses, is that everyone should strive to fight against injustice even if they aren’t directly affected.

But Habib and her colleagues aren’t just fighting for the rights of women. After taking a sip from her espresso, she takes my pen and draws two intersecting circles on my notepad. She labels them: nationality and statelessness. “These issues are related,” she explains.

The story begins in 1932 when Lebanon conducted its one and only demographic census, which would determine how many seats each sect was allotted in Parliament. Thousands of Muslims were left out of the census to ensure that Christians had powerful representation.

CRTDA has championed this cause as part of its campaign, including a dramatic 2013 protest of more than 1,000 people in downtown Beirut. “She didn’t just talk about empowering women,” says Joumana Merhi, a women’s rights activist who has known Habib for more than 15 years. “Lina, like many activists, confronted the entire political class.”

Habib keeps the issue alive by penning columns and reports. As the executive director of the Women’s Learning Partnership — a coalition of 20 feminist organizations from the global south — she co-organized a conference that brought several Arab feminists to Beirut in August. Like in Morocco, they discussed new strategies to push for equal nationality laws across the Middle East.

Her work has earned her enemies and drawn smear campaigns, including an accusation that CRTDA was carrying out a Qatari plot to naturalize Palestinian refugees — who were uprooted during the creation of Israel in 1948 — to stop them from returning. Laughing off rumors, Habib vows to continue fighting against Lebanon’s sectarian system. But when asked what keeps her going, she pauses. “I don’t know what else I would do,” she says, after a moment. “I wouldn’t be able to rest until the issue is resolved.”

OZY

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.