By Max Boot

By Max Boot

BEIRUT- Imagine 125 million refugees flooding into the United States (population: 328 million). That is what Lebanon has experienced on a per capita basis. Since 2011, this nation of 4 million people has seen an influx of some 1.5 million refugees fleeing the Syrian civil war next door. “I find it a miracle this country hasn’t exploded,” a Western diplomat told me last week. “Most countries would never have allowed this to happen.”

This is the dog that didn’t bark — perhaps the most surprising good-news story in the Middle East. Lebanon has always been on the verge of collapse because of divisions among Sunnis, Shiites, Druze and Christians. In 1975, the growing power of Palestinian refugees upset the delicate sectarian balance and triggered a civil war that ended only in 1990, when the Syrian regime of Hafez al-Assad occupied the country.

In 2011, when a rebellion broke out against Assad’s son, Bashar al-Assad, Lebanon could not remain aloof. Hezbollah, the Shiite militia, sent fighters to save the Alawite-dominated Syrian regime. (Alawism is a Shiite sect .) Sunni extremists retaliated with terrorist attacks in Lebanon. It was easy to imagine the Syrian civil war engulfing this small Mediterranean nation. But it didn’t happen. Why not?

Part of the answer has to do with searing memories of the Lebanese civil war. None of the sectarian groups want to revisit that nightmare. Though Lebanon’s government is often paralyzed by political gridlock, it has continued to function — and, at least when it comes to the security services, to function effectively. The Lebanese Armed Forces, buttressed by U.S. aid, have coordinated with Hezbollah, buttressed by Iranian aid, in a campaign to clear Islamic State and al-Qaeda militants out of their strongholds along the Syrian border. But Lebanon could never have coped with the refugee influx were it not for the support of the United Nations — and in particular of the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the world body’s refugee agency.

“If UNHCR weren’t taking the lead, it would have catastrophic repercussions,” Bassil Hujeiri, the mayor of Arsal, told me. Hujeiri should know: His town of 40,000 in the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon’s north has been inundated by 40,000 Syrian refugees. It also became a base for Syrian jihadists who terrorized the locals before finally being routed in a military offensive. The newcomers put a severe strain on already inadequate infrastructure, especially electricity, garbage collection, housing and water treatment. The Lebanese state lacked the resources to cope; even in Beirut, the electricity regularly flickers off. Enter UNHCR, which invited a small group of U.S. policy analysts last week on a tour of its Lebanese operations from Tyre in the south to Tripoli in the north.

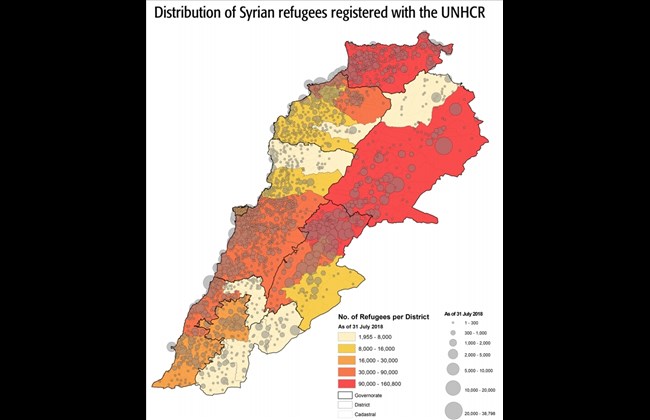

UNHCR and its partners help provide housing, medical care, education, food and, in some cases, modest cash stipends to the desperately poor refugees, two-thirds of whom live on less than $4 a day. There are no sprawling tent cities here. Refugees live in threadbare, cinder-block apartment buildings and small clusters of tented structures scattered across the country. This means they will not become a state within a state as the Palestinians did, but it also spreads the burden of coping with their needs to every municipality.

It’s easy to bash the United Nations, as President Trump did before the General Assembly last week. There is much to criticize, from wasteful spending to anti-Israel rhetoric. But in Lebanon — which has one of the highest number, per capita, of U.N. aid workers in the world — the global organization is performing an invaluable role in keeping a tinderbox from going up in flames.

The U.N. agencies present here range from the U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees , which runs 12 Palestinian refugee camps, to the U.N. Interim Force in Lebanon, an 11,000-strong peacekeeping force that serves as a buffer between Israel and Hezbollah in southern Lebanon. No agency has been more important in recent years than UNHCR, which has taken the lead in coping with the 5.6 million refugees who have fled Syria, primarily to Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon, as well as more than 6 million internally displaced people in Syria.

UNHCR will be needed here for years to come. The Syrian refugees I met expressed a desire to return to their homeland — eventually. But even with the war waning, as Assad consolidates his authority with Russian and Iranian help, few are willing to risk an immediate return. They fear detention in Assad’s torture chambers or conscription in his brutal army.

The United States could ameliorate the refugee problem by taking in more of the Syrians, but the Trump administration cruelly refuses to do so. (Total number of Syrian refugees from Lebanon admitted to the United States this year: one, according to UNHCR.) Failing that, the United States has a moral and strategic imperative to support UNHCR and other humanitarian agencies. And, despite the president’s isolationist sentiments, Washington is continuing to do just that: The United States was UNHCR’s biggest donor in 2017. Thanks to bipartisan support in Congress, that support is likely to remain constant this year. It is money well spent to alleviate suffering, prevent the radicalization of the refugees and avert the disintegration of the fragile Lebanese state.

WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.