You can accuse President Donald Trump of many things. But after his controversial press conference Monday with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, Finland, some critics have called his actions treason. Do lawyers agree?

You can accuse President Donald Trump of many things. But after his controversial press conference Monday with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Helsinki, Finland, some critics have called his actions treason. Do lawyers agree?

“Donald Trump’s press conference performance in Helsinki rises to & exceeds the threshold of ‘high crimes & misdemeanors,’” tweeted former CIA Director John Brennan. “It was nothing short of treasonous. Not only were Trump’s comments imbecilic, he is wholly in the pocket of Putin. Republican Patriots: Where are you???”

Brennan’s premise for the accusation is that Trump appeared to back Putin over U.S. intelligence agencies‘ assertion that Russia interfered in the 2016 election.

Putin denies what the U.S. intelligence community has told Trump—that the Kremlin used cyberwarfare to undermine American democracy. And Trump, whose 2016 campaign is under investigation by special counsel Robert Mueller for possible collusion with the Russian government, seems to believe Putin.

“I have President Putin. He just said it’s not Russia,” Trump told reporters after the pair met. “I will say this: I don’t see any reason why it would be…. I have great confidence in my intelligence people, but I will tell you that President Putin was extremely strong and powerful in his denial today.”

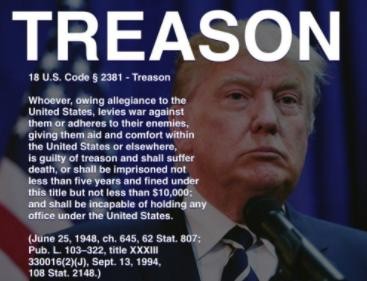

According to 18 U.S. Code § 2381: “Whoever, owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere, is guilty of treason and shall suffer death, or shall be imprisoned not less than five years and fined under this title but not less than $10,000; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.”

And in Article III of the U.S. Constitution, it says: “Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court.”

Laurence Tribe, the Carl M. Loeb University professor and a professor of constitutional law at Harvard Law School, told Newsweek: “If one defines war to include cyberwar—e.g., by deliberately hacking into a nation’s computer-based election infrastructure—then what we witnessed in Helsinki was President Trump openly aiding and abetting the Russian military’s ongoing war against America rather than protecting against that Putin-led cyber-invasion.

“That, in turn, could reasonably be defined as treason within the meaning of 18 USC § 2381 and Article III of the U.S. Constitution.

“Some scholars would resist that modern definition as one the authors of the Constitution could not have contemplated, and others would insist on limiting the definition to situations involving a state of formally declared war, but views like Brennan’s are far from wild,” said Tribe.

Jens David Ohlin, vice dean and professor of constitutional law at Cornell Law School, told Business Insider, “Trump is clearly helping Russia—whether it rises to the level of ‘aid and comfort’ would be for a jury to decide or for the House of Representatives to decide if it pursues articles of impeachment.”

John Shattuck, professor of practice in diplomacy at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, wrote in The Boston Globe, “Trump’s pre-summit comments implied that he would not use the tools of diplomacy, law, or military technology to defend the United States against continuing Russian cyberattacks. If true, this would be tantamount to giving aid and comfort to an enemy.”

Shattuck added: “The president’s hostility to the U.S. investigation of Russian cyberattacks, his failure to impose a cost on Russia for the attacks, his denigration of U.S. alliances, and his eagerness to have ‘an extraordinary relationship’ with the Russian leader all point toward giving aid and comfort to an enemy.”

But Ross Garber, a lawyer and adjunct professor at Tulane Law School, who has represented state governors in impeachment trials, does not believe the Constitution can be stretched or interpreted to regard Russia as an enemy against which the U.S. is at war.

“No matter how repugnant one might consider the president’s statements in Helsinki, they do not meet the constitutional definition of ‘treason,’ which is very narrow and addresses providing aid to an ‘enemy,’” Garber told Newsweek. “Russia is not technically an enemy because we are not at war with it. These matters are far too important to allow partisan aims to diminish serious constitutional analysis.”

In February 2017, when the Russia investigation was beginning to unfold amid accusations of treason leveled at members of the Trump campaign, Carlton Larson, professor of law at the University of California, Davis, also concluded that Russia could not be considered a formal enemy of the United States.

“Speaking against the government, undermining political opponents, supporting harmful policies or even placing the interests of another nation ahead of those of the United States are not acts of treason under the Constitution,” Larson wrote in The Washington Post at the time.

According to Larson, “Enemies are defined very precisely under American treason law.”

“An enemy is a nation or an organization with which the United States is in a declared or open war,” Larson wrote. “Nations with whom we are formally at peace, such as Russia, are not enemies. (Indeed, a treason prosecution naming Russia as an enemy would be tantamount to a declaration of war.)

“Russia is a strategic adversary whose interests are frequently at odds with those of the United States, but for purposes of treason law it is no different than Canada or France or even the American Red Cross.

“The details of the alleged connections between Russia and Trump officials are therefore irrelevant to treason law.”

The White House did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.