By Diana Spechler

At Akramawi, a 65-year-old hummus joint by Damascus Gate in Jerusalem, a cook named Nader Tarawe was showing me how to prepare hummus. The recipe for hummus b’tahini (as the dish is named; ‘hummus’ simply means ‘chickpeas’), consists of chickpeas, tahini, garlic and lemon. Since it’s relatively simple to make, the variations lie more in how it’s served. Should it be it smooth or lumpy, heavier on the tahini or on the chickpeas, crowned with fava beans or more chickpeas or pine nuts or ground beef? And what’s on the side? Chips? Pickles? Hot sauce? Falafel?

Tarawe topped each plate of hummus with a dollop of tahini and a sprinkling of olive oil. “Oil is good,” he said, an accidental Middle East metaphor. Hummus is a regional metaphor, too: beloved all over the world, it’s yet another source of tension, yet another question of proprietorship. Who invented the dish? Who can claim it as their own?

Everyone from the Greeks to the Turks to the Syrians have tried, but there’s little evidence for any theory. Most of the ingredients have been around for centuries: the chickpea dates back more than 10,000 years in Turkey and is, according to a , Syrian-Lebanese author of several Middle Eastern cookbooks, “one of the earliest legumes ever cultivated.” And tahini, the sesame paste that is vital to hummus b’tahini, is mentioned in a 13th-Century Arabic cookbooks . But the combination of ingredients that make up the popular dish is harder to pin down.

“It’s a Jewish food,” said chef Tom Kabalo of Raq Hummus in Israel’s Golan Heights a few days later. “It was mentioned in our bible 3,500 years ago.” I was in his restaurant eating his Tuesday special. Because it was October, the special was ‘Halloween hummus’, garnished with shredded pumpkin and black tahini.

He’s not the only one who told me that hummus is biblical. Kabalo and others are referring to a passage from the Book of Ruth, part of the third and final section of the Hebrew Bible: “Come hither, and eat of the bread, and dip thy morsel in the hometz.”

While it’s true that hometz does sound like hummus, there’s also a good reason to believe otherwise: in modern Hebrew, hometz means vinegar. Of course, ‘dip your bread in vinegar’ would be an odd expression of hospitality, so therein lies the uncertainty.

“I’ve heard claims that it was first cultivated in northern India or Nepal,” said Oren Rosenfeld, writer and director of ” Hummus! The Movie . Said Liora Gvion, author of Beyond Hummus and Falafel: Social and Political Aspects of Palestinian Food in Israel, “I think it is an old and stupid debate that is not worth one’s attention.”

But for many, the question of where hummus comes from is absolutely a matter of patriotism and identity. The now legendary ‘Hummus Wars’ began in 2008 when Lebanon accused Israel of cashing in on what they believed should have been Lebanon’s legacy, publicity and money. The president of the Association of Lebanese Industrialists, angry that hummus had come to be known and marketed throughout the west as an Israeli dish, sued Israel for infringement of food-copyright laws. The Lebanese government petitioned the EU to recognise hummus as Lebanese. Both efforts proved ineffectual.

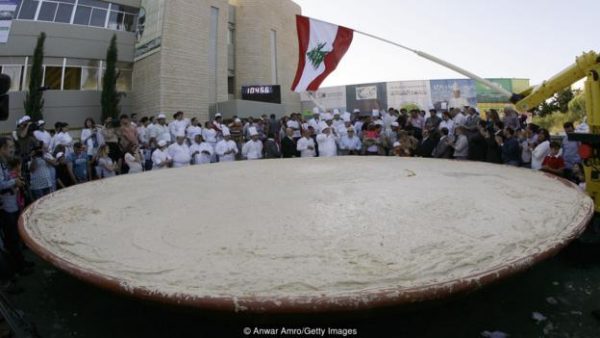

Cultural appropriation is a hot topic in the food world (just ask the Peruvians and Chileans who owns pisco, for example), so the hummus debate could have generated an interesting conversation. Instead, the whole thing devolved into the culinary version of a dance-off: in 2009, Fadi Abboud, Lebanese minister of tourism, decided that the way to settle the matter once and for all was for Lebanon to make a plate of hummus so large it would be recognised by the Guinness Book of World Records. The goal was achieved, the record set with a plate of hummus that weighed around 2,000kg. In response, Jawdat Ibrahim, a famous Arab-Israeli hummus joint in Abu Ghosh, Israel, retaliated with hummus served in a satellite dish that had a diameter of 6.5m – about 4,000kg of hummus. Then the Lebanese counter-attacked with 10,452kg of the dip – the number of square kilometers of Lebanon. They have held the record since 2010.

Most people who talk about the Hummus Wars hold Rosenfeld’s diplomatic view. But American food historian Charles Perry, president of the Culinary Historians of Southern California and an expert on medieval Arab food, gives Lebanon some credit.

“I tend to take the Lebanese claim somewhat seriously,” he said. “Beirut would be my second choice in response to the question of who invented hummus. It stood out as a sophisticated city throughout the Middle Ages, one with a vigorous culinary tradition, and lemons were abundant there.”

But Damascus, Syria, strikes him as the more likely candidate. He explained that the traditional way of serving hummus throughout much of the Middle East is in a particular red clay bowl with a raised edge. The hummus is whisked around briskly with a pestle so that it mounds up along that edge. Not only does this present the hummus conveniently for picking up with bread, it proves that the hummus has the proper texture, neither too slack nor too stiff.

“The practice of whipping hummus up against the wall of the bowl indicates a sophisticated urban product, not an ancient folk dish. I’m inclined to think hummus was developed for the Turkish rulers in Damascus,” Perry said.

Explaining his choice, he continued: “Nobody can say who invented hummus, or when. Or where, particularly given the eagerness with which people in the Middle East borrow one another’s dishes. But I associate it with Damascus in the 18th Century because it was the largest city with a sophisticated ruling class,” he said.

However, another popular theory says that hummus is neither biblical nor Lebanese nor Syrian, but Egyptian. “The earliest recipe I’ve seen for hummus that includes tahini is from an Egyptian cookbook,” said Middle East historian Ari Ariel, who teaches history and international studies at the University of Iowa. Cookbooks from 13th-Century Cairo describe a dish made of cold pureed chickpeas, vinegar, pickled lemon and herbs and spices. Many claim that it’s the hummus we enjoy today. But is it fair to consider those recipes hummus b’tahini if there’s no tahini? No garlic?

Back at Akramawi, I sat at a communal table where I met Noam Yatsiv, a tour guide from the Israeli port city Haifa, who takes his hummus very seriously. He told me that he eats hummus five times a week and has a dog named Hummus, and that hummus comes from Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Palestine.

“All of them?” I asked.

Yatsiv shrugged. He told me that it doesn’t matter where it’s from. What matters is the way it’s been co-opted and sold commercially in grocery stores in plastic containers. “That’s not hummus!” he said, tearing a piece of pita. “There should be a sign on that hummus the way there is on ‘kosher shrimp’. It should be labelled ‘fake hummus’. There should be an international law.”

But the hummus solidarity I found on my travels was the result of a different question. There was common ground among just about everyone I met who slings hummus for a living – from Tarawe at Akramawi to the Christian Maronite family who run Abu George Hummus in the Old City of Acre, Israel, to the hipsters at Ha Hummus Shel T’china in Jerusalem’s Nachlaot neighbourhood who give their leftover hummus to the homeless each night – every time I asked, “What’s your secret ingredient?”

Almost everyone answered, “Love.”

BBC

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.