By Phillip Carter and Loren DeJonge Schulman

More than any other president-elect in recent memory, Donald Trump has sought out military brass to populate his inner circle. Trump announced Thursday that he wants retired Marine Gen. James Mattis as his defense secretary — a post traditionally designated for a civilian. Trump is also considering retired Army Gen. David Petraeus for secretary of state, retired Marine Gen. John Kelly for secretary of state or homeland security, and Adm. Michael S. Rogers as the director of national intelligence. His national security adviser-designate, Michael Flynn, retired from the Army as a lieutenant general after decades as a military intelligence officer. And CIA Director-designate Mike Pompeo graduated from West Point and served during the Cold War as an Army officer.

There is a great American tradition of veterans holding high political office, from Presidents George Washington and Dwight Eisenhower to senior officials such as Secretary of State Colin Powell in the George W. Bush administration and national security adviser James Jones in the Obama administration. A typical administration, though, starts out with few recent generals in key positions. Filling as many slots with retired brass as Trump is poised to do is highly unusual.

No doubt these men bring tremendous experience. But we should be wary about an overreliance on military figures. Great generals don’t always make great Cabinet officials. And if appointed in significant numbers, they could undermine another strong American tradition: civilian control of an apolitical military.

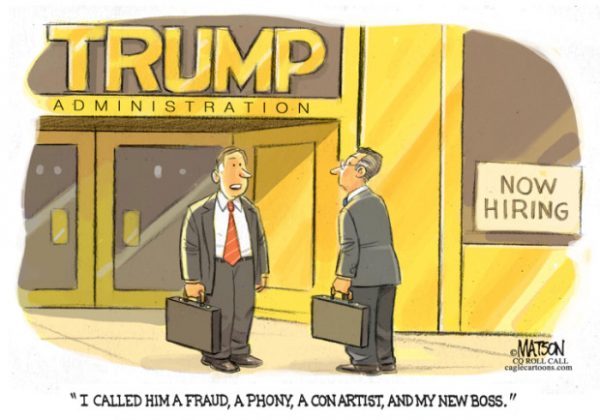

Trump was often dismissive of military leaders during his campaign. He boasted that he knew more than the generals did about fighting the Islamic State. He repeatedly criticized them for broadcasting their attack strategies before the fact. He said they had been “reduced to rubble” under President Obama and even threatened to remove some of them once he took office.

Still, it’s understandable why he would embrace them now. The military enjoys the highest approval rating of any institution in American society. And hiring former generals is a sure way to gain legitimacy — whether the president is a first-term senator from Illinois seeking cover on his Iraq withdrawal, or a reality television star and casino mogul who lost the popular vote and has a reputation as a foreign policy neophyte.

Of course, Trump’s picks have implications beyond political theater. And perceived legitimacy shouldn’t be confused with the likelihood of success in high civilian offices.

Like any prospective employees, veterans should be judged on their merits beyond rank or military service. The historical record shows that veterans with similar pedigrees can perform very differently when appointed to high offices. Consider the cases of retired Air Force Lt. Gen. Brent Scowcroft, who was national security adviser to Presidents Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush, and Army Gen. Alexander Haig, who served under President Ronald Reagan as secretary of state. Each came to his role with impeccable military credentials and considerable experience in Washington. Scowcroft performed brilliantly, running an effective National Security Council that stewarded U.S. foreign policy as the Cold War ended, the Soviet Union broke apart and the United States fought the Persian Gulf War. Haig performed poorly, causing (or nearly causing) several civil-military crises with his military-esque assertion that he was in charge following the assassination attempt on Reagan and with his blustery diplomacy toward the Soviet Union. Haig resigned a year and a half into the administration.

It’s impossible to know whether Trump’s veterans would be more like Scowcroft or more like Haig.

Mattis, the warrior-monk, displayed his strategic and operational genius as a Marine general, but wrangling the Defense Department bureaucracy is a different matter. As our colleague Erin Simpson wrote, he viscerally disdains the minutiae and machinery of the Pentagon. “Budgets, white papers, and service rivalries, not to mention the interagency meetings and White House meddling — these tasks are not what you go to Jim Mattis for,” she argued. “Not only does the role of secretary of defense not play to Mattis’ strengths, but success in that role would compromise much that we admire most in him: his bluntness, clarity, and single-minded focus on warfighting. The secretary’s job is by necessity much more political than all that. You can’t run the Pentagon like the First Marine Division.”

Flynn is an iconoclast whose record of scorched-earth leadership at the Joint Special Operations Command and the Defense Intelligence Agency does not augur well for how he might manage the National Security Council process or get rival agencies to work together. Even Flynn’s greatest success — the building of the Joint Special Operations intelligence machine under Gen. Stanley McChrystal — probably won’t translate well in his new role. Flynn succeeded at the JSOC because of the unique battlefield conditions of his job, his narrow mandate and the incredible leadership capabilities of his boss, whose force of personality helped knit together the “team of teams,” as McChrystal called it, that JSOC became.

Petraeus epitomizes the modern U.S. military leader, but his leadership style did not graft well onto the CIA and would probably be an even worse fit at the State Department or another agency.

Relying on the brass, however individually talented, to run so much of the government could also jeopardize civil-military relations.

Our founders embedded civilian control of the military in our Constitution for good reasons: They wanted to avoid a military dictatorship and limit the potential for military coups. “War is in fact the true nurse of executive aggrandizement,” James Madison wrote in 1793. And so they formalized checks and balances by making the president the commander in chief, while vesting Congress with the power to declare, regulate and fund war.

This principle was later strengthened in the National Security Act of 1947, which mandated that the secretary of defense come from civilian life and prohibited appointment within 10 (later seven) years of relief from active duty. An exception was made for the appointment of Army general and former secretary of state George Marshall in 1950, but lawmakers emphasized then that “no additional appointments of military men to that office shall be approved.”

Mattis — who retired from active duty only three years ago — will need Congress to pass new legislation if he is to serve. Teaming him with several other retired officers in the Cabinet and on the National Security Council would not require congressional approval, but it would be similarly precedent-shattering. “Civilian control is so fundamental to the character and the way we think about the United States,” former Pentagon strategist Jim Thomas told The Washington Post’s Greg Jaffe. “It’s something that should be preserved at all costs.”

Traditional civil-military relations focus on the ways the president and Cabinet engage with the military and make decisions, a vertical dimension that has always been complex. Historically, it was viewed as a one-way command relationship, in which presidents would set objectives for generals, and the generals would figure out how to get the job done. Contemporary scholars such as Eliot Cohen (who served in the George W. Bush administration) and Janine Davidson (who is currently undersecretary of the Navy) describe the relationship now as an “unequal dialogue” of civilian guidance and military advice among actors, agencies and interests that results in decisions by the president. Cohen says it is a “conflictual collaborative relationship, in which the civilian usually (at least in democracies) has the upper hand. It is a conflict often exacerbated by the differences in experience and outlook. . . . These differences are not ideological but temperamental, even cultural.” Davidson builds on Cohen’s point, adding that “as long as these differences do not lead to the bureaucratic equivalent of lines drawn in the sand, they can enrich the process by which strategies are debated and decided. By expecting and accommodating a degree of friction, the national security system also avoids the groupthink that arises when friction is absent.”

How Trump’s generals, should they serve, would behave in this ecosystem — and how they would relate to subordinate generals, to whom they have been friends, rivals or commanders — remains an open question. It’s unlikely that hiring generals for the Cabinet would instantly lead to good civil-military relations. It may, in fact, cause deterioration. The deliberate tension of the civil-military dynamic may be magnified by Trump’s criticisms of the military leadership, or by existing (and not uniformly positive) relationships between Trump’s slate of veteran leaders and today’s general officers. On the other hand, the potential for veterans to align with their active-duty counterparts may skew some of the healthy tension built into the relationship.

Alongside the vertical dimension of civil-military relations, there is also a horizontal dimension: how the military relates to other instruments of U.S. power, such as intelligence, diplomacy and finance. Here, the great risk of Trump picking so many generals echoes the old proverb: When you have a hammer, all problems begin to look like nails. This risk is particularly acute now, after 15 years of war, when the military has achieved such policy and budget primacy, and military tools are often looked to as options of first, rather than last, resort. It is not obvious that retired military officers are the right people to better use nonmilitary tools of statecraft.

And there is a societal dimension of civil-military relations that may suffer by the appointment of retired military leaders to high office. The share of veterans in society is in decline, a result of a smaller military, the lack of conscription and a growing population. Concerns abound about the civil-military divide, and how the military should relate to society when a shrinking percentage of Americans serve in uniform or have a personal connection to those who do. Senior military leaders have spent their entire adult lives inside the bubble of the force — living in America’s most exclusive gated communities, in an insular society that has its own legal code, language and customs. Our military is both a part of America and apart from America. Generals and admirals emerging from this environment may be stellar leaders and military professionals, but they make unlikely ambassadors to bridge the civil-military divide. This is true even for generals such as Mattis and Petraeus, great students of civil-military relations who have each written on the subject.

Mattis, in his new book with Kori Schake, “Warriors and Citizens,” highlights the difference between civilian and veteran approaches to policymaking, writing that “veterans are believed to be more hesitant to use military force than civilians.” However, Mattis and Schake add that “military leaders often try to leach the politics out of political decision making in order to better analyze problems and develop strategy; this can lead to ‘perfect’ solutions impractical for consideration by elected officials whose portfolios are broader than the military mandate alone.” This is the essence of the challenge facing senior military leaders promoted to the political level: how to appropriately consider nonmilitary factors, including electoral politics and the will of the people, when making decisions for the country.

Finally, Trump’s embrace of the generals may undermine the apolitical, professional ethos at the heart of our all-volunteer force. Former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey implored his fellow generals and admirals to “not become part of the public political landscape” during the 2016 election. Although he was speaking of political endorsements, the concerns Dempsey raised offer a useful guidepost for why administrations should be thoughtful in offering political appointments to retired military officers.

The greatest risk posed by Trump’s rush to court the brass is the extent to which our military leadership may become, in reality or perception, a politicized institution. This might, as Dempsey surmised, lead “future administrations . . . to determine which senior [military] leaders would be more likely to agree with them before putting them in senior leadership positions.” In the short term, Trump may be satisfied with a politicized military that seems more responsive to him. In the long run, however, both the Trump administration and our national security will suffer if his appointments undermine the institutional integrity of the military and corrupt its leadership in service of political ends.

Phillip Carter is a former Army officer and Pentagon official who leads the military, veterans and society program at the Center for a New American Security. Loren DeJonge Schulman is a former Pentagon and National Security Council official who is deputy director of studies at the Center for a New American Security.

WASHNGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.