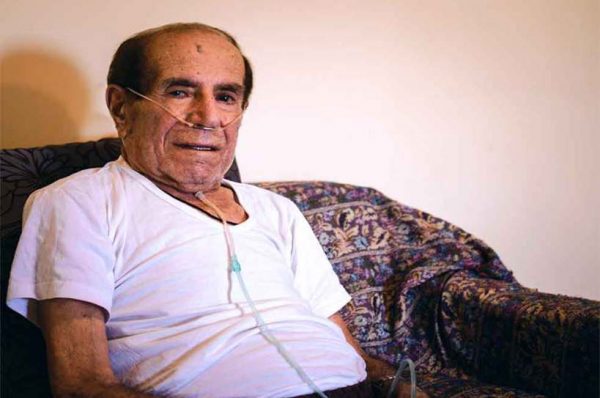

For 86-year-old Adib Nouwar, Lebanon’s garbage crisis is a matter of life and death. Any irritation induced by the slightest of elements, even the smell of fried food and dust, can be enough to trigger a respiratory fit as his lungs struggle from years of pollution and stress. Under the weight of thick smoke that too often invades his home in Dekwaneh, a suburb north of Beirut, Adib suffers as he is moved from room to room while his family rushes to shut all windows and doors. He manages a frail smile for a photo from behind an oxygen mask, which has become his constant companion.

Wassim, Adib’s son, is both livid and hopeless. He feels let down by the local municipality, the government, and the Lebanese people who he says are complacent and indifferent. Lebanon’s garbage crisis has entered its second chapter with trash making headlines once again after a brief hiatus. And for families like the Nouwar family, it’s an unwelcome sequel.

Dekwaneh, like other lower- and middle-income suburbs around Beirut and Mount Lebanon that include Dora, Bourj Hammoud, and Jdeideh, has bore the brunt of the garbage crisis. It began in 2015 when the country’s main landfill was closed and authorities failed to provide an alternative. Streets filled with trash, and protests erupted.

Finally, authorities offered up a “fix” earlier this year which stipulates the opening of two landfills in Bourj Hammoud and Costa Brava in Choueifat, southeast of Beirut. Minister of Agriculture Akram Chehayeb has repeatedly said this approved plan is the only way forward.

Following negotiations, the protests were lifted, but the garbage remained. The Bourj Hammoud municipality and the Tashnag party, Lebanon’s largest Armenian political party which has its headquarters in Bourj Hammoud, announced that no rotting trash would be allowed into said landfill, leaving it up to municipalities to discard of the waste.

According to Minister of Agriculture Chehayeb, no municipality is exempted from environmental laws that ban trash burning and those who breach regulation could face charges. But trash accumulated, and having no other means to resolve the issue, many resorted to open incineration and temporary stacking on bridges and highways.

A widely shared image of a ‘trash bridge’ in Jdaideh, approximately three kilometers form Bourj Hammoud, shows the material consequences of the trash crisis.

The result of the growing mistrust between local representatives and the government is simply more trash on the streets. While filming mounds of trash being burned around the Dora area on September 25, 2016, a friend and I almost had an accident as a waste container was left in the middle of the highway.

Trash piled up on a discontinued bridge next to a mall in Beirut. 3KM from where I lived. Glad not anymore. #Lebanon pic.twitter.com/AP1XLWopmB

— Rafael (@Arm_nuke) September 19, 2016

“On some mornings it’s a challenge to make it from my home into my car,” Wassim says. “The toxic fumes makes it difficult and sometimes we even see hordes of invasive insects –flies and ticks—in our neighborhood as the trash remains.”

On the onset of Lebanon’s trash crisis, which began in July 2015, and after rounds of governmental deals on the issue, many thought the situation was under control. But that was simply not the case as garbage reemerged during the hottest months of summer 2016, August and September, adding strain to struggle.

Wassim expressed his lack of trust towards his municipality:

I haven’t filed any complaints simply because I do not trust my municipality; they run the place like gangsters and eliminate dissent mafia style. They shoot stray dogs and at one point even launched a crusade against homosexuals, beating them openly. This is why many suffer in silence.

Doctors in Lebanon say they are seeing a spike in severe respiratory diseases tied to the ongoing trash disaster. The crisis has already taken its toll on many, especially children, the elderly and those with respiratory illnesses and a weak immunity. In July 56-year-old Bourj Hammoud mother of four Rozine Moughalian and her family were forced to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars through crowdfunding for a liver transplant, which doctors linked to exposure to toxins in the area. Countless other cases have also been reported.

Many continue to suffer, and for people like Adib, retirement and rest in his own home have become a luxury he cannot afford. Wassim emphasized the toll this is taking on his father:

My father should be able to at least breathe normal city air and not to be surrounded by smoke from open waste incineration … This morning I woke up before my alarm set off because of the smell. I rushed into his room and it was filled, like the entire house, with fumes. It’s unbearable! If the smell of fried food can kill him, what chance does he have against this? We moved him around and closed all doors and windows to prevent as much smoke as we can from entering.

How much can we really expect from a government whose sole concern throughout the entire crisis has appeared to be one over profit division and money making, especially since no one seems to be able to identify the culprits? A question that seems to have no answer.

As Wassim told Newsroom Nomad:

I returned home late one night around 3 am only to find a huge fire in a nearby makeshift factory dumpsite. In an attempt to identify the culprits I drove to the location of the blaze only to find municipality police vehicles all over the place. I don’t know why but they were just there; some parked, while others were roaming. So, I thought it wasn’t a good idea for me to be noticed while taking pictures.

GLOBAL VOICES

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.