By: RUSSELL CRANIAL

By: RUSSELL CRANIAL

In a country where schoolchildren draw pictures of food instead of eating it, getting rid of the foul, corrupt President would be a step in the right direction. But only a step.

Venezuela has popped on and off the pages of the U.S. mainstream media in recent months, but in the past few weeks it’s been mostly off. That might give the impression that somehow things have improved. That impression would be wrong. Things have gotten arguably worse, but how many times can reporters write essentially the same story?

On the other hand, space limits in the MSM prevent reporters from telling the story in sufficient detail to allow North Americans to understand what is actually going on. So what most have written over and over again has still left too much out. I can sum up the basic situation with a riddle, whose answer will not be hard to guess: What struggling democracy features political language taken from Animal Farm, repressors that resembles the bad guys in Woody Allen’s Bananas, and shopping queues straight out of Soviet times? Right.

The nearly 200,000 Venezuelans who surged over the Simón Bolívar International Bridge into Colombia on the weekends this past July all had different things on their shopping lists, but shared one thing common: What they were looking for could not easily be found, or turned out to be far beyond their means. One Venezuelan woman even told a Reuters journalist that she was crossing the bridge into Colombia hoping to buy a Cesarean section kit for her pregnant daughter. Early this year I happened to be standing on this very bridge with my Davidson students investigating the Colombia-Venezuela diplomatic and border crisis. With contraband being readily smuggled across the fast-moving current a stone’s throw away, the border scene was surreal.

Thanks to high inflation and shortages stemming from the inability to import, Venezuelans can’t afford to eat or purchase basic household goods and medicines, and even when they can, there is little supply to choose from.

On any given day in Caracas, Venezuela’s capital, lines snake around city blocks in the balmy heat of the tropical clime, waiting for the stores to unlock their doors. This queuing is not a product of absurd sales, a la Black Friday, but rather demand for basic items: flour, meat, diapers, and medicine. In the western city of Maracaibo, desperation even leads groups of hungry Venezuelans to ambush food delivery trucks.

In recent months, the simple act of shopping at the grocery store has become a miserable all-day/all-night affair, with shoppers queueing for hours. Though the Venezuelan government assigns shoppers a particular day of the week to do their grocery shopping based on their national identification number, people will line up a day in advance to guarantee a spot in line, only to find an extremely limited selection of goods once they make it through the doors. The government asserts that this system prevents the bachaqueo, or reselling of goods at higher prices, but neglects to address the bigger problem: There are simply not enough goods to go around.

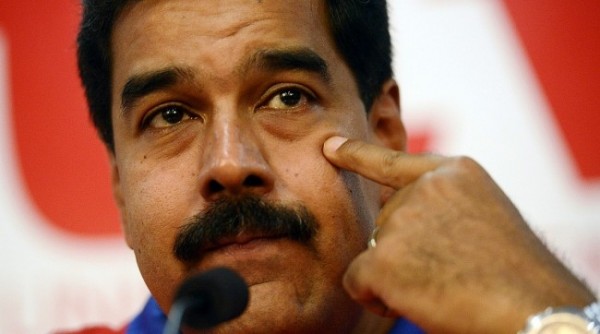

During such a crisis of epic economic and humanitarian proportions, what are the best tools of effective governance? If you answered mass arrests, empty proclamations, vigorous suppression, and paltry subsidies, you might find your political equal in Nicolás Maduro, the polarizing President of Venezuela. In Maduro’s Venezuela, the rules of the game are constantly changing, leaving the livelihood and basic well-being of millions of Venezuelans in flux.

Venezuela’s late President Hugo Chávez crafted his distinctive version of the high-spending, leftist state and the ideology of “Bolivarian socialism.” During the Chávez era, literacy rates soared, subsidized food and gas supported many poor Venezuelans, and an anti-yanqui and anti-imperialist fervor dominated foreign-policy discourse. The larger-than-life Chávez, whose eccentricity and egomaniacal tendencies are perhaps best exemplified by his weekly television program, Aló Presidente, died of cancer in 2013, leaving his less-charismatic Vice President, Maduro, in charge of the country.

After serving out the remainder of Chávez’s term and winning an election haunted by allegations of questionable electoral processes, the failures during Maduro’s Administration continue to disenchant and disappoint fervent chavistas and even members of his own party, the PSUV, who were accustomed to the generosity of the Chávez years.

How did Venezuela, whose oil revenues formerly made it the wealthiest country in Latin America, end up in a situation where food is so scarce and expensive? Dissecting the root causes of the crisis is easy enough, but solutions are more difficult to come by.

The Bolívar (Not So) Fuerte

There is no way to understate the severity of the current economic situation in Venezuela. The numbers themselves tell all: 700 percent inflation, a black market exchange rate 15,000 times greater than the central bank’s official stated rate, and an estimated 30 percent of schoolchildren who are malnourished. Venezuela’s Bolívar Fuerte, the official name of the currency whose literal translation is (now, ironically) the “strong Bolivar,” plummeted as worldwide oil prices began to tank in 2013—the very commodity on whose sales revenue almost the entirety of the Venezuelan economy depends. By that time, however, Venezuelan government spending on social welfare programs had already outpaced the revenue needed to fund them. Still, Maduro maintains that the current economic struggles are part of an ongoing “economic war” spearheaded by the the gringos, and neglects to make productive fixes to the nation’s currency and supply woes.

The country operates with two different exchange rates, a preferential rate that stands around 10 bolivars to U.S. $1, and a more expensive rate around 600 bolivar to U.S. $1. Because the foreign currency supply is so low and difficult to attain for the average Venezuelan, however, dollars cost even more on the black market: upwards of 1,500 bolivars to the dollar. With such small foreign reserves at this point, economists forecast that Venezuela will need additional loans next year, or risk a major default.

Multinational corporations and other foreign investors have already pulled out or tabled further investments in Venezuela for the time being, further worsening the country’s cash flow problems. Venezuela cannot afford to import goods from abroad, nor is its domestic production sufficiently robust to supply more food itself, leading to the dismal variety of products populating store shelves.

Venezuela’s moneyed class, which is relatively small yet does still exist, has the resources to import food and other basic goods from abroad, but poorer Venezuelans who depend on government-subsidized goods are stuck with whatever is available to them at the grocery store by the time they get through the doors. These shortages have pushed desperate citizens to loot stores and factories, which often results in violence, sometimes fatal. Add the past year’s rationing of energy and electricity, and it becomes very clear that Venezuela is struggling to provide the basic services on which its citizens depend.

In efforts to grant the Venezuelan state more control in the food production process, Maduro issued an executive decree to oblige workers to spend sixty or more days working in the fields to mitigate food shortages. He also empowered the Bolivarian Armed Forces to oversee the distribution and importation of food, promoting General Vladimir Padrino López to the position of “Superminister.” Giving the army a drastically increased amount of influence bears particular significance as the country becomes ever more restless and angry.

Erosion of Democracy

With each passing week, Maduro manipulates the Venezuelan system to his best advantage, issuing new executive decrees and cracking down in ways that will best maintain his control of the country. His statements and actions threaten to usurp what remain of democratic norms and the will of the Venezuelan people, whose frustration continues to grow.

In December 2015, when the opposition coalition Mesa de Unión Democrática (MUD) won a supermajority’s worth of seats in the National Assembly, it seemed a huge opportunity to change the course of Venezuelan politics and impose a newfound check on Maduro’s power. Celebratory feelings were short-lived, however, as the President quickly nullified the victories of a handful of legislators via a ruling by the Supreme Tribunal of Justice, an institution whose members were largely appointed by Maduro and adjudicate squarely under his thumb. In July, Maduro even threatened to do away with the National Assembly altogether, claiming that they no longer served any useful purpose and should “say goodbye to history, because their time is up.”

Time will likely be up for Maduro soon as well, as the opposition spearheads a well-organized effort to recall the President from office. The Venezuelan recall referendum, enshrined in Chávez’s 1999 constitution, consists of three steps: the collection of signatures from 1 percent of the electorate, followed by signatures from 20 percent of the electorate, then, finally, the actual recall vote itself. If the recall referendum goes through and is tallied honestly, it is all but certain that Maduro will lose; polls estimate that anywhere from 70 to 80 percent of Venezuelans will vote to remove the President from office.

Having turned in the signatures of 1 percent of the Venezuelan electorate in late June, the opposition waited for the National Electoral Council (CNE) to announce the timeframe for the next step in the recall process, the collection and certification of the signatures of 20 percent of the electorate, which would mandate that a recall referendum be held. Once the CNE finally announced the timetable, it was determined that the 20 percent benchmark signature collection drive would “probably” occur in October, even allowing for ample turnaround time for the CNE to certify the signatures. With this timeline, the recall vote would take place in 2017.

This timing, however, is problematic for the opposition. A successful recall in 2016 would require fresh elections. But while a recall vote after January 2017 would remove Maduro from his post, it would merely replace him with his acquiescent Vice President, Jorge Arreaza, for the remainder of his term—a de facto victory for the Maduro Administration and its allies. Maduro and the PSUV continue to implement additional methods to prevent a successful referendum from occurring, including firing of government employees who signed the recall petitions, as well as refusing to acknowledge the political parties organizing the recall vote.

After the CNE’s timing announcement, opposition groups began planning massive September 1 protests called the “Taking of Caracas,” hoping to pressure the government into an earlier recall election. Nearly one million protesters, including a number of pro-government demonstrators, gathered in the streets for a mostly peaceful demonstration. It was not without government attempts to thwart the event, however: members of the international press, including reporters from NPR, the Miami Herald, and Al Jazeera, were denied entrance to the country or deported, and social media reports showed that police erected roadblocks on highways leading into Caracas. Maduro’s Administration congratulated itself on thwarting an alleged coup on the heels of the protests, convening a meeting with foreign diplomats to share the intelligence, and hoping to leverage their findings into even harsher treatment of the opposition.

Armed primarily with social media and promoting nonviolent resistance to spur progress, the opposition is united in its desire to see Maduro out the door, setting aside any political differences for the time being to achieve the greater goal. Following a delayed and politically motivated trial, opposition leader Leopoldo López was sentenced to 14 years in prison in 2015 for allegedly instigating violence in 2014’s massive anti-government protests that left 43 protesters dead. In August 2016, he lost his re-sentencing appeal. At the end of the same month, Daniel Ceballos, former Mayor of San Cristóbal and also an opposition leader, was whisked away from his home, where he was already under house arrest, in the early hours of the morning by members of Venezuela’s intelligence agency. His wife documented Ceballos’s surprise detention a video on Twitter, as intelligence forces shuttled him back to a prison cell.

Too Little, Too Late?

So, with the economic odds stacked against recovery anytime soon and a sluggish referendum process, how do you solve a problem like Maduro and his perpetuation of Venezuela’s ongoing crisis?

The so-called international community is largely staying passively engaged, swiftly condemning acts of political oppression and threatening punishment for Venezuela, but largely kicking the can of accountability down the long and winding road. In a potential sign of progress, Maduro broke from his steadfast resistance to external assistance and agreed to start a dialogue with the opposition through mediation with Pope Francis and the Vatican. Leaders from Spain, Panama, and the Dominican Republic are helping to mediate between the two sides, though dialogue appears to have stalled amid the recall referendum controversy.

With Venezuela due to accept the rotating presidency of the regional trade bloc, Mercosur, certain member countries are loathe to hand over authority to a country slipping ever further from democracy. Afraid to make a final decision, Mercosur has again delayed the naming of a new presiding nation, this time until the end of 2016. Member countries like Argentina and Brazil, formerly part of the “pink tide” of South American countries with leftist leaders, have backpedaled swiftly away from Maduro and company as new, Right-leaning governments have come into power this year. Maduro has also found an adversary in member country Paraguay, after asserting the “corrupt, drug-smuggling Paraguayan oligarchy” was out to get Venezuela.

Meanwhile, the Organization of American States, the international body that Maduro loathes most (he has accused newly inaugurated OAS president Luis Almagro of being a CIA operative), is hesitant to intervene in the issue. The general consensus is that Venezuelans themselves must take the initiative for and direct political change, not outside actors. Like Mercosur, the OAS balked at outright censure of Venezuela, debating the invocation of the Inter-American Democratic Charter without holding an official vote. Old League of Nations officials would have been proud.

So far, the Obama Administration has kept a low profile, lest it be blamed for hatching or aiding Venezuela’s calamity, but along with everyone else it is watching with alarm. The country’s all-too-painful implosion is not good for anybody, and there is nothing to suggest, as Syria so painfully reminds us, that things still cannot get worse, much worse. Venezuela’s tumult—and its effect on the Bolivarian government’s petro-dollar influence—is a significant regional development, especially concerning Cuba. It is not a coincidence that Havana’s historic diplomatic outreach to the Obama Administration occurred right as subsidized crude oil and refined oil shipments from Venezuela plunged by roughly half. Indeed, Havana must cover the difference with its own funds—never an easy task in its dysfunctional fiscal universe.

Low oil prices have been a temporary balm, as has post-reconciliation travel from the States, but higher petroleum prices could provoke a crisis. Cuban President Raúl Castro is slated to hand over power to his successor, who is likely to be the civilian yet hardline apparatchik Miguel Díaz-Canel, in 2018. Whether this sort of “reform” will be sufficient to convince the U.S. Congress to modify or repeal the embargo is an open question. But the very fact that Obama seems, if anything, to have benefited from the opening suggests we can expect growing pressure on Congress to finally put a dagger in this Cold War anachronism par excellence.

Whenever crippled Venezuela begins to see signs of economic recovery, the crisis of recent years will have already left significant damage in its wake. A nation lauded regionally and internationally for its scholars is now so strapped for food that primary schoolchildren and their teachers faint for lack of nourishment, left to draw pictures of the food they so desperately need instead of being able to consume it.

It would be foolish to assume that Maduro’s departure from office will resolve Venezuela’s problems swiftly; though his decisions have certainly complicated and compounded the Venezuelan situation, the fall of Venezuela’s oil revenues that propelled the crisis to its current critical point is unlikely to be reversed soon. Maduro himself is not the source of every problem contributing to the country’s current woes.

In any case, his grip on power is eroding as time goes on and Venezuelans get hungrier for change. If polling is any indication, Maduro’s departure will be widely celebrated, but the real challenges will remain once the recall ballots are cast and counted. For the time being, however, Maduro certainly isn’t providing much of a remedy for Venezuela’s ills, and continues to be a large part of the problem himself.

TAI

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.