The town of Halba in Lebanon is not far from the border with Syria, and it feels like it.

Driving into town you can sense a tension, and see a heavy Lebanese military presence, in some ways not unlike Northern Ireland 20 or 30 years ago.

The problem for the Lebanese is that the nearby border is porous, and the authorities are interested in finding out who might have crossed it, and with what intentions.

But the security implications pale in comparison to the humanitarian ones.

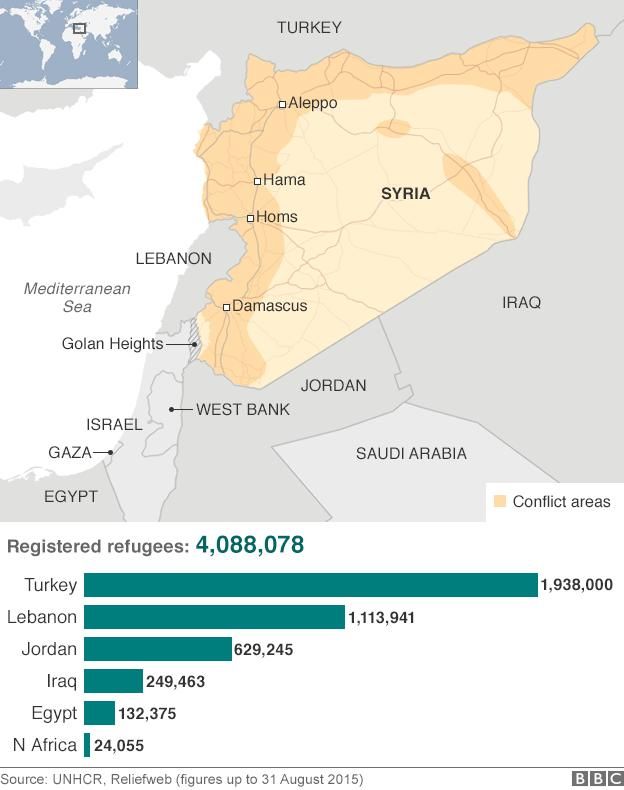

That’s because in just four years, 1.5 million Syrians, fleeing the civil war, have crossed into Lebanon.

It’s a figure made all the more astonishing by the fact that Lebanon has about 4 million people to begin with.

I’ve travelled here with Peter Anderson, the head of Concern Worldwide in Northern Ireland, who has come here on a fact-finding mission.

He is used to dealing with humanitarian crises, but even he is taken aback at the scale of what has happened in Lebanon.

“That’s the equivalent of Northern Ireland taking in 400,000 or the UK taking in 20 million, and yet the Lebanese people, despite the poor infrastructure and the level of poverty, have accommodated these people,” he says.

Elke Leidel, from Germany, is Concern’s country director in Lebanon.

Her worry is that the refugee crisis in Europe is becoming the only story, and that much-needed global attention is being turned away from the problem in the Middle East.

“When we discuss the refugee crisis in Europe, we need to see what is happening here in the Middle East,” she says.

“It cannot be that because there is now a crisis in Europe, that part of the funding would go to Europe. We need the funding here.”

The task facing their organisation is a formidable one. In this one district of Lebanon, Concern is supporting 150,000 Syrian refugees across 135 different camps.

The Lebanese government does not allow the refugees to settle in large scale camps, perhaps because when it built similar camps for hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, they became permanent settlements.

That means that Syrians must build temporary shelter where they can – on pieces of waste ground in the town centre, or in fields in the countryside.

In one such camp, I meet a man who back in Syria was a lawyer. Now his children go barefoot.

He is deeply frustrated because he can no longer provide for them, but at least his family have one thing; their father is alive.

Elsewhere I meet Khaldye, who lives in a ramshackle rented room with her six children.

Her husband was a dentist in Syria. One day he went out, and simply never came home.

Not long afterwards Khaldye and her children walked to the Lebanese border, where they were stopped by the army.

She and the children simply stood there for two days and nights until the soldiers relented and let them cross.

Now, the family only survive because two of her sons aged 11 and 13 work picking vegetables, and the pittance they earn helps to feed their siblings.

Back home, the boys might have expected to enter Syria’s professional classes. Now they’re unlikely to see the inside of a classroom again.

Here in Halba, and other towns like it along Lebanon’s border with Syria, the scale of the human suffering is immense. And with another winter of snow and freezing temperatures about to set in, it is about to get worse.

As I leave, it is clear to me that whilst the European migrant and refugee crisis is a big story back home, it isn’t the only story.

And Lebanon, whilst its people and its government have done what they can, is a country now teetering under an almost impossible weight.

Declan Lawn’s report from Lebanon is part of a Spotlight programme on how people from Northern Ireland are responding to the refugee crisis. It is on BBC One Northern Ireland at 22:35 BST on Tuesday and will be available to watch afterwards on the iPlayer.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.