This is the second in a series of reports adapted from the Legatum Institute’s “Beyond Propaganda”

program.

On May 9, 2015, the Syrian Arab News Agency website carried the following headlines on its home page:

“Homs Clock ticks again, declaring the return of life to the Old City”;

“Army foils terrorist attack in Daraa”;

“Mikdad: Legendary struggle of Syria is an outcome of its people’s achievements”;

“Syria wins gold medal in the high jump in Moscow Open Cup.”

But reality was far less rosy than the headlines suggested. In the preceding weeks, rebels had captured a

provincial capital, the Syrian pound had plummeted in value, and cracks had appeared within the highest

echelons of the security establishment.

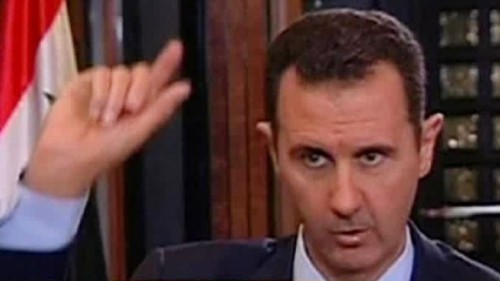

At first glance, the SANA headlines seem like the stereotypical behavior of an authoritarian government

(and indeed of a few liberal-democratic ones), trying to hoodwink people into believing the regime is

stronger and more competent than it actually is. On closer inspection, however, this does not seem

adequate motivation. Syrian citizens have access to a range of websites and satellite channels offering a

portrait of the country different than SANA’s. Moreover, they know things are going badly in the fighting

when soldiers from their town or village do not come home. Indeed, President Bashar al-Assad himself

acknowledged military “setbacks” in a public address on May 6, 2015.

If simple persuasion or indoctrination is not the aim, what is the function of these slickly produced state

news items, whose production values suggest a surprising degree of financial commitment when the

government is running out of money? After more than four years of a devastating war of attrition, there

cannot be many people even inside the fortress of Damascus who look around them and see the Syria

depicted on state news — a land where the army is always “thwarting” terrorists and the citizens are at

leisure to enjoy bicycling championships. So what sort of complex game of signals is the Syrian regime

and its population involved in?

To begin to understand Assad’s use of propaganda, we need to go back to the rule of his father, Hafez alAssad,

who seized power in 1970 after a series of destabilizing internal coups and filled the top levels of

the security establishment with trusted allies. On the face of it, Hafez’s position was precarious: He was a

rural upstart from the minority Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shiism in a majority Sunni Muslim country.

Yet through the secular ideology of Baathism (a hodgepodge of Arab nationalism and socialism) and

ruthless suppression of dissent, he managed to fashion the Syrian state in his image.

Legitimacy was derived from Soviet-backed macro-projects, dam building, and irrigation. But ministries

and parliament were ultimately irrelevant: The state was inseparable from the ubiquitously represented

person of Hafez. Outside the presidential household, the official discourse of Baathism and hyperbolic

praise for the leader was all-permeating, and the penalties for violating it high.

Hafez is notorious for brutally crushing an uprising of the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood in 1982, in which

thousands of people were killed and the city of Hama flattened. But the fear he engendered spread far

beyond that event, through a Stasi-style system which encouraged citizens to inform on each other’s

behavior to the intelligence services. “From the moment you leave your house, you ask, what does the

regime want?” a Syrian told Lisa Wedeen, professor of political science at the University of Chicago and a

Middle East specialist. “People repeat what the regime says. The struggle becomes who can praise the

government more…. after 10 years, it becomes its own language. Everyone knows who knows the language

better and who is willing to use it. Those who are self-respecting say less, but for everyone the language is

like a seat belt.”

As Wedeen notes, the claims that this “language” required people to uphold were palpably absurd — that

Hafez was the country’s premier pharmacist, for example. And unlike O’Brien, the torturer in George

Orwell’s 1984 who breaks Winston Smith until he truly believes that two plus two equals five, the regime

did not seem interested in creating genuine conviction, merely the external appearance of it — what

Wedeen calls “a politics of ‘as if.’” Disbelief in the official pieties was registered in jokes and even some

slyly encoded commentaries that made it into the public sphere.

After deliberating on why the regime would insist on the external trappings of loyalty, Wedeen concludes

that the falseness is itself the point. “The regime’s power resides in its ability to impose national fictions

and to make people say and do what they otherwise would not,” she writes. “This obedience makes people

complicit; it entangles them in self-enforcing relations of domination, thereby making it hard for

participants to see themselves simply as victims of the state’s caprices.”

When Bashar came to power after his father’s death in 2000, he was seen as a breath of fresh air. He

helped introduce the Internet to Syria and presided over some limited but nonetheless tangible reforms.

There was a little more tolerance of grumbling, so long as it did not touch on the president himself, and a

little less heavy-handedness. “We used to get sent to prison for writing things that caused offense,” said

one journalist in 2005. “Now we only have to pay a fine!”

Bashar himself seemed to be popular, greeted with fervent applause wherever he went, though the politics

of “as if” make it hard to tell how deeply rooted this popularity was. The urban middle classes, at least, felt

that he represented their aspirations for Syria. One woman, shopping in a Damascus mall in 2011, shook

her head in wonder as she recalled the privations of the pre-reform economy: “There were no diapers, no

milk, no bananas. We only had oranges and apples!”

Despite the slight relaxation, the logic underpinning the regime was the same, and when the rules of its

game were violated, it responded with disproportionate ferocity. When, in March 2011, a group of

teenagers graffitied a wall in the southern town of Deraa with slogans from the Egyptian revolution, the

security services arrested and later tortured them. Protests erupted at the teenagers’ treatment, quickly

spreading to other parts of the country. Increasingly, the protesters focused on the symbols of the regime.

In video after video uploaded to YouTube, posters of Bashar were torched and statues of Hafez hacked

down in a campaign of visual “cleansing” (“hamlat al-tathir”). The pact of the “as if,” on which the power

of the Syrian regime rested, was being repudiated.

It was nearly two weeks into the escalating cycle of protests and crackdowns before Assad made a public

statement on the unrest. Optimists hoped that this young, Western-educated president would offer

historic concessions, an inclusive vision to save the country. In the event, however, Assad’s address to

parliament on March 30, 2011, merely repeated the familiar rhetoric about reform and Syria being the

subject of an international “conspiracy,” claiming the protests and crackdowns had been manipulated in

order to undermine Syria’s role as a “resistance” state. The parliamentarians applauded him, but even

non-opposition Syrians were shocked at how little the speech offered. One Christian businessman told the

Guardian that the speech had left the Baath Party “empty-handed” as it faced the Syrian people.

Apart from some initial conciliatory gestures, Assad did not invest much political capital in trying to win

back the rural Sunni majority: His speeches seem to have been primarily aimed at bolstering his

supporters — Alawites, Shiites, Christians, and the urban middle classes. Joshua Landis, a historian of

Syria, argues that given the decades of repression that had preceded it, Assad was bound to act this way:

“If Assad had done what he should have done,” i.e. offer meaningful concessions, “there would have been

revenge, his cronies would have been hung from the wall,” he said. “So many people know who killed their

brothers and who tortured them, and they would all want justice.”

Right from the start, both sides were involved in a war of perception. The opposition wanted to create the

impression that the momentum was with them and that the regime was reverting to barbarism in

response, while the regime needed to make people feel that the unrest was contained and its response was

proportionate and responsible.

To impose his narrative, Assad could not simply prevent people from seeing videos of protests and

crackdowns recorded by activists: Satellite dishes carrying foreign news channels were everywhere. In any

case, the videos were all over the Internet. But while he could not censor, Assad could cause people to

question the veracity of the opposition’s material. To achieve this, pro-Assad media described foreign

news channels as part of a “conspiracy” against the regime. A cartoon, pinned to the wall of the Syrian

border-control office at the crossing point from Lebanon, depicted Syria as a dove of peace surrounded by

guns marked “Al Jazeera,” “Al Arabiya,” and “France 24.” In September 2011, the pro-government.

Addounia TV station even claimed that Qatar had built life-sized replicas of the main squares of Syria’s

cities in order to stage protests there, which were then filmed by French, American, and Israeli directors.

As a Syrian journalist quoted in the Financial Times explained, the aim of such outlandish claims was not

so much to convince people that they were true as to pollute the epistemological landscape. “The aim is to

confuse people,” the journalist said. “It is not even necessary for people to believe it, just as long as it

makes them confused and unsure about what is really going on.”

Assad’s confusion strategy was helped by the fact that pan-Arab channels were indeed owned by the elites

of gulf countries who eventually became openly committed to the overthrow of his regime. It has also

helped that elements of the opposition have undoubtedly circulated false claims at various points to

bolster their narrative. Post-uprising Syria seems a good illustration of the theory that the availability of

large quantities of information can actually help a regime stay in power, provided that the information is

unreliable.

This logic has also helped the regime internationally. In interviews with the international media, Assad

has unequivocally denied using either chemical weapons or barrel bombs against his own people. So firm

are his denials, and so polarized the international media landscape in which they occur, that credible

evidence implicating the regime put forward by human rights organizations ends up becoming so much

more noise in the din.

Few have done more to amplify that din than Assad’s allies in Moscow. When, for example, the world was

first digesting news of what appeared to be a chemical weapons attack in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta

in August 2013, RT (a Russian state-funded TV network) ran a feature suggesting that the YouTube videos

of the victims were fabricated in advance because their date stamp was one day before the attack was

supposed to have occurred. As was quickly pointed out, YouTube videos are stamped with California time,

ten hours behind Damascus.

Back home, as the civil war has continued, the regime’s domestic priority has been to convince its forces

to fight. The army is thought to have been reduced by half following mass desertions and casualties, and

the regime has relied heavily on irregular forces, largely from the Alawite community, supplemented by

Shiite fighters from Lebanon and Iraq. The regime has traditionally abjured sectarian discourse in its

official channels, yet at the same time, its foot soldiers depend on the sense of community and the

perception of a shared threat that sectarian identity creates. By late 2013, evidence of this sectarian

mobilization was all over Damascus: The flag of the Lebanese Shiite militia was hoisted over a vanquished

suburb, and pendants depicting the sword of Shiite martyr Ali with Assad’s face superimposed on the hilt

were on sale in the souqs.

Yet even as the regime was outsourcing vital state security functions to sectarian militias, “Sunni” and

“Alawite” remained taboo words in the official media, the well-known reality (in this case of sectarianism)

once again being ignored. The usefulness of this kind of coverage to the regime is that it signals the

ongoing presence of the state. It may be fear of getting massacred by Islamist gunmen that prompts

Alawites to fight, but they need to feel that what they are fighting for is a state, not a sectarian warlord: A

long-running sectarian war can only end badly for the minority sect.

And so, even as the coercive power that allowed the regime to impose its version of reality frays and the

state itself withers, official media goes on in the traditional style, not out of denial but as an evocation of

the fictions that bound the country together for so long.

In Egypt, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the former army chief voted president after ousting the country’s

democratically elected Muslim Brotherhood leader Mohammed Morsi, is in a very different position than

Assad. The state has deeper roots in Egypt than in Syria, institutions have some actual power, the country

is much more religiously homogenous, and Sisi himself enjoys significant public support. But the power

of crowds over presidents has been tasted, and anyone ruling over 80 million people with an aiddependent

budget and an unstable relationship with other centers of power within the state needs to keep

a close eye on the people’s mood. As in Syria, stagecraft has played an important role.

The coup itself was spectacularly well-scripted, with Sisi making his televised announcement flanked by

liberal leader Mohamed ElBaradei, the sheikh of Al-Azhar University, the Coptic pope, and youth

activists. Having the air force trail heart shapes in the sky was a detail some Hollywood directors might

have considered too much, but it seemed to go down well.

For all the professionalism of the pageant, there is something strangely studied and derivative about Sisi’s

public image. He has implicitly compared himself to Gamal Abdel Nasser, the iconic army officer whose

leadership saw Egypt’s influence peak. It is an identification his supporters have taken up enthusiastically

in a million memes and posters of the two men side by side. Yet, as various commentators have pointed

out, there is nothing particularly Nasserist about Sisi’s policies, which so far seem to echo the economic

neo-liberalism of Hosni Mubarak rather than the defiant socialism of the earlier leader.

The classic strongman signals do not only come from Sisi’s association with Nasser. Shortly after the July

2013 coup, security forces violently dispersed pro-Muslim Brotherhood protesters in Cairo, killing

hundreds. Since the ousting of Morsi and particularly since Sisi was voted president in June 2014, a

number of laws have been passed shutting down space for dissent in the name of fighting terror; the

Muslim Brotherhood has been outlawed, protests banned, and media freedoms restricted.

Nonetheless, no ruler’s head lies easy in today’s Middle East. Mekameleen TV, a pro-Brotherhood satellite

channel based in Turkey, has been broadcasting what it claims are leaked recordings of Sisi’s private

conversations, causing him huge political embarrassment. His pitch to the Egyptian people was stability,

but the war on terror is not going well — hundreds of policemen have been killed by a Sinai-based

insurgency since the ousting of Morsi. The economy is improving but still critically dependent on Gulf

handouts. In this context, some see Sisi’s strongman behavior as a simulacrum of strength rather than

evidence of it. “National unity to the point of xenophobia, cult of personality — they are the classical

leitmotifs for regimes that are not strong but feel themselves to be brittle,” says Professor Andrea Teti of

Aberdeen University.

As Egypt commentator Sarah Carr points out, four years of instability have created an audience eager to

believe in the performance. The army’s narrative of recent events has stuck, she writes, and it is not

simply because of its undoubted influence over the media: “People themselves want — seemingly need —

to believe it.”

The violent tumult of the post-Arab Spring environment and the associated rise of border-spanning

sectarian identities have shown quite how much state authority is a matter of performance, symbol, and

spectacle in parts of the Middle East. There has always been a touch of staginess to the Middle Eastern

state. As Nazih Ayubi points out, a preponderance of flags and uniforms can be read as an indicator of

weakness rather than strength. In the case of Assad’s Syria, the state is more present in the eagle motifs

which are supposed to represent it than in most people’s lived reality. SANA’s plodding stories cloak the

charred ruins of cities with the familiar discourse of the Baathist state, and with the options as they are in

today’s Middle East, it is perhaps not surprising that some people continue to act “as if” they believe in it.

Sometimes even a fictional state is preferable to the alternative.

Foreign Policy

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.