The tiny Mediterranean country could have almost 100tn cubic feet (tcf) of offshore gas reserves, according to some officials. But rather than exploit a potentially transformative opportunity, politicians have engaged in politics as usual — bickering and stalling as neighbouring Syria’s war worsens an already toxic sectarian environment.

“Politicians are definitely not in the mood for a grand bargain,” says Ayham Kamel, director for the Middle East and north Africa at Eurasia Group, the risk consultancy. Still, he expects some progress, even if halting, within two to five years.

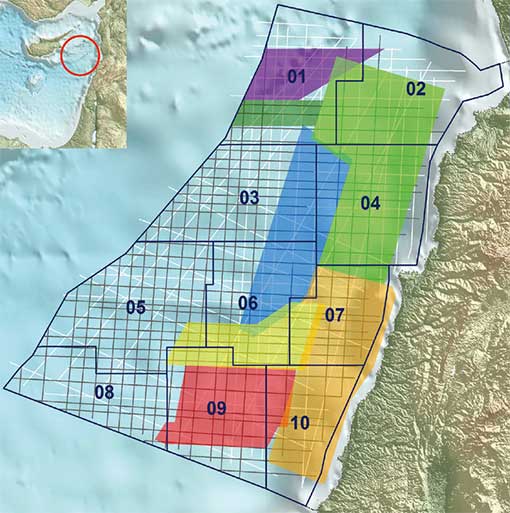

Lebanon lags behind Israel, Cyprus and even its war-torn neighbour Syria — all have already awarded companies exploration rights. But unlike them, its petroleum administration has already completed extensive research using 3D seismic data it says covers about 80 per cent of offshore sites. Substantial finds would be game-changing for the country of about 4m people, grappling with one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the world. Wissam Chbat of the Lebanese Petroleum Administration says just one of the country’s estimated 10 offshore blocks could potentially supply it for 60 years.

“Lebanese local demand can easily be satisfied, leaving a lot of spare capacity for export if these numbers turned out to be true,” he says.

Such development could end the daily power outages and infrastructure problems that have plagued Lebanon since its 1975-1990 civil war.

With no oil and gas service infrastructure, Mr Chbat also points to investment opportunities such as building pipelines or liquefied natural gas (LNG) processing plants as the sector develops. Because the government will also require oil companies to field a work force that is 80 per cent Lebanese, there would be demand for education and training services.

Yet for the 46 companies pre-qualified to bid in Lebanon, initial excitement has dimmed after two years of waiting for constitutional decrees to be agreed by the Lebanese cabinet. The cabinet, which ceased meeting earlier this year due to political disputes, has yet to approve two decrees delineating the number of blocks for exploration and outlining a revenue mechanism and taxation policy. Without them, Lebanon cannot issue a tender for exploration rights.

“Even if he was to launch the tender today, with oil prices where they are and oil companies looking to focus on key assets, I’m not certain the bid round would be very successful,” says Samer Khalaf, a regional expert for Neftegaz, a Russian-owned oil and gas company, which has already been invited to bid once a tender is issued.

Officials blame the country’s political vacuum — Lebanon has not had a president for more than a year, a symptom of dysfunction exacerbated by Syria’s war. Syria has long dominated its smaller neighbour’s politics and the war reverberates along its own sectarian lines.

Observers privately say politicians are jockeying for the potential sector’s local contracts to grease their sectarian-based patronage networks.

They may even have an interest in delaying due to the country’s political stalemate, says Mr Kamel. “Whoever passes the law gets a lot of credit. No one wants to give the other side a big win.”

As newcomers to the energy industry, Lebanese politicians say they first need to sort out issues such as revenue distribution and how much gas to use domestically. They are wary of setting the process in motion without a united vision.

If the cabinet approved the two decree drafts, a tender could be issued within six months. But there is no sign of a breakthrough.

Another pressing problem is that Lebanon’s proposed fiscal structure, which calls for taxing revenues as well as splitting profits, is less appealing with oil prices so low.

As politicians struggle over gas that has not even been found, their options may diminish as companies’ disillusionment grows.

“You have companies that think, ‘Today these guys . . . are not able to have two decrees issued’,” Mr Khalaf says. “What will happen later when we have to invest and to drill a well?”

FINANCIAL TIMES

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.