On a visit to Syria early this month, Major General Qassem Soleimani, commander of the Quds force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, Iran’s external strike force, promised a surprise. “The world will be surprised by what we and the Syrian military leadership are preparing for in coming days,” he said enigmatically.

While the meaning of this runic bravado has still to be revealed, it is well known what Gen Soleimani does for a living. He is the man who, along with the Iran-backed Lebanese paramilitaries of Hizbollah, two years ago constructed a nationwide militia network that all but saved the embattled minority regime of Bashar al-Assad, when it looked vulnerable to mainly Sunni rebels. This is a formula he is repeating with Shia militia in Iraq to insulate Baghdad from the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis).

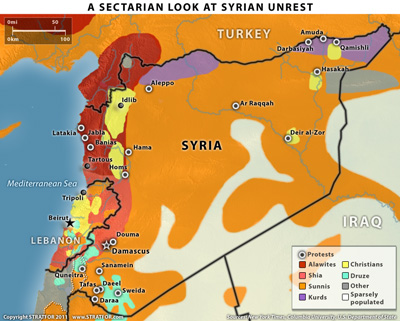

But in recent months, Assad forces have started losing ground again — to Isis jihadis in central and eastern Syria, and to a rival Islamist alliance in the north and mainstream Sunni rebels in the south.

Syrian Kurdish fighters, meanwhile, have inflicted a string of defeats on Isis to strengthen their grip on the northeast of the country. What is left of the Syrian army, severely depleted after four years of civil war, looks to be pulling back to defensive lines — reinforced by the IRGC and Hizbollah.

The regime still holds Damascus, but the capital could soon be threatened from the south, where rebels are poised to capture Deraa on the border with Jordan. They have already taken a neighbouring military base while the government has reportedly evacuated its administration from the city — which is what it did before the northern city of Idlib fell in March. Another rebel group, furthermore, maintains a strong position in the eastern reaches of Damascus.

North of the capital, Hizbollah has been fighting for six weeks to clear jihadis out of the Qalamoun mountains that bestride the Lebanese border with Syria, not just to protect Lebanon but to secure the road from Damascus through Homs to the northwest coast and the mountainous heartland of the Alawite sect, an esoteric offshoot of Shiism that has been the backbone of Assad family rule for more than four decades.

There, the main change in recent weeks is the arrival in the coastal city of Latakia of IRGC and Hizbollah forces, according to knowledgeable Arab sources. These combined reinforcements already number 3,000, they say, with another, more mixed militia force of about 1,500 north of Latakia. Tehran, they add, is organising an ongoing air bridge into the enclave.

If this is Gen Soleimani’s surprise then — given the Assad regime’s chronic manpower shortage — it was sort of anticipated. Already, by early May, well-placed Arab and European sources were reporting significant inflows of IRGC and Hizbollah fighters.

As Mr Assad’s rump state shrinks further, his near total dependence on Iran and its auxiliaries has never been clearer. What seems to be hardening, though, is the pattern of de facto partition emerging in Syria — just as it is in Iraq.

The Iraqi state was shattered after the US-led occupation gave way to increasingly sectarian leaders from the Shia majority who alienated already largely self-governing Kurds and the Sunni minority pushed aside with the toppling of Saddam Hussein. Always irreconcilable elements of Saddam’s regime are now the backbone of Isis and its self-declared, cross-border caliphate.

But the Assad regime played a part in this too. It funneled Sunni extremists into Iraq after the Anglo-American invasion of 2003 — using the same routes they now use back into Syria.

From the beginning of what began as a civic uprising against tyranny in 2011, Damascus has been peddling the plaintive story that it was up against al-Qaeda.

From the outset, too, the regime has used sectarian scare tactics to hold its thinning ranks together. That Syria then became a magnet for jihadi extremists was a self-fulfilling prophecy brought about by the Assad regime’s recourse to sectarianism and savagery.

An estimated 250,000 have been killed on both sides, and tens of thousands more have died subject to starvation or denied access to medical care.

Half the population has been displaced and vast swaths of cities such as Homs and Aleppo have been razed. As Syria fragments, could this suffering be nearing its end?

Bashar al-Assad, though commonly thought to lack the cunning of his late father Hafez al-Assad, has often been lucky. The results of this month’s general election in Turkey may turn out to be another stroke of luck for him.

The ruling party of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has sworn to oust Mr Assad, lost its majority.

The three opposition parties disagree on many things but all want to turn off the Turkish pipeline of arms and volunteers into Syria. That may not be the Soleimani surprise, but it could change the battlefield dynamics in northern Syria.

FINANCIAL TIMES

UPDATE: Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has relieved Major General Qassem Soleimani,the Al Qods Brigades chief and supreme commander of Iranian Middle East forces, of his Syria command after a series of war debacles. He was left in charge of Iran’s military and intelligence operations in Iraq, Yemen and Lebanon according to an exclusive report by Israeli website DEBKAfile based on Iranian and intelligence sources.

It appears that Soleimani’s Syria surprise was his sacking if the Debka file report is correct.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.