In building his political career, Turkey’s powerful and charismatic prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, relied heavily on the support of a Sufi mystic preacher whose base of operations is now in Pennsylvania.

In building his political career, Turkey’s powerful and charismatic prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, relied heavily on the support of a Sufi mystic preacher whose base of operations is now in Pennsylvania.

The two combined forces in a battle with the country’s secular military elite, sending them back to the barracks in recent years and establishing Turkey as a successful example of a moderate, democratic Islamic government.

Now a corruption scandal not only threatens Mr. Erdogan’s rule but has exposed a deepening rift between the prime minister and the followers of his erstwhile ally that is tearing the government apart.

On Thursday, after several days of sensational disclosures of corruption in Mr. Erdogan’s inner circle, Istanbul’s police chief was dismissed as the government carried out what officials indicated was a purge of police officers and officials conducting the corruption investigation — nearly three dozen so far, according to the semiofficial Anadolu news agency.

Following much the same strategy he employed as he battled thousands of mostly liberal and secular-minded antigovernment protesters this summer over a development project in a beloved Istanbul park, Mr. Erdogan is portraying himself as fighting a “criminal gang” with links abroad.

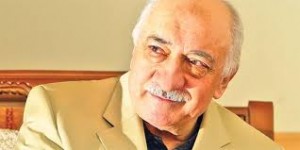

That is an apparent reference to Fethullah Gulen, the Pennsylvania imam who adheres to a mystical brand of Sufi Islam and whose followers are said to occupy important positions in Turkey’s national government, including the police and judiciary but also in education, the news media and business.

That is an apparent reference to Fethullah Gulen, the Pennsylvania imam who adheres to a mystical brand of Sufi Islam and whose followers are said to occupy important positions in Turkey’s national government, including the police and judiciary but also in education, the news media and business.

Mr. Erdogan weathered the summer of protest, emerging with the support of his base even as his image abroad was tarnished. But the corruption investigation, started by the Istanbul chief prosecutor, poses a challenge that analysts and some Western diplomats believe could be even greater. The inquiry has ensnared several businessmen close to him, including one major construction tycoon, the sons of ministers and other government workers involved in zoning and public construction projects.

Mr. Erdogan and Mr. Gulen have disagreed on a number of important issues in recent years, although the tensions were kept largely silent.

Mr. Gulen was said to have opposed the government’s activist foreign policy in the Middle East, especially its support of the rebels in Syria. He is also said to be more sympathetic to Israel, and tensions flared after the Mavi Marmara episode in 2010. That was when Israeli troops boarded a Turkish ship carrying aid for Gaza and killed eight Turks and one American of Turkish descent, leading eventually to a rupture in relations — since patched up — between Turkey and its onetime ally.

Mr. Gulen’s followers “never approved the role the government tried to attain in the Middle East, or approved of its policy in Syria, which made everything worse, or its attitude in the Mavi Marmara crisis with Israel,” said Ali Bulac, a conservative intellectual and writer who supports Mr. Gulen.

The escalating political crisis, experts say, underscores the power Mr. Gulen has accumulated within the Turkish state. That power threatens to divide Mr. Erdogan’s core constituency of religious conservatives ahead of a series of elections over the next 18 months.

Mr. Gulen left Turkey in 1999 after being accused by the then-secular government of plotting to establish an Islamic state. He has since been exonerated of that charge and is free to return to Turkey, but never has. He lives quietly in Pennsylvania, though his followers are involved in an array of businesses and organizations in the United States and abroad, and some of them helped start a collection of charter schools in Texas and other states. He rarely gives interviews, and a spokesman recently said he was too ill to meet with a reporter.

But a lawyer for Mr. Gulen, Orhan Erdemli, said in a statement released to the Turkish news media and shared by Mr. Gulen on Twitter that “the honorable Gulen has nothing to do with and has no information about the investigations or the public officials running them.”

Huseyin Gulerce, who is personally close to Mr. Gulen and is a writer for a Gulen-affiliated newspaper, said Mr. Gulen’s followers have many of the same complaints about Mr. Erdogan that the protesters had this summer. They believe that Mr. Erdogan has become too powerful, too authoritarian in his ways, and has abandoned his earlier platform of democratic overhauls and pursuit of membership in the European Union. “This is not a group that Mr. Erdogan is not familiar with,” Mr. Gulerce said. “He knows all of us personally, from the time he was mayor of Istanbul. He has known Mr. Gulen personally for 20 years.”

“It was the Mavi Marmara crisis that created the first cracks,” in their relationship, Mr. Gulerce said. “Mr. Gulen’s attitude was very clear, as he always suggested that Turkey should not be adventurous in its foreign policy and stay oriented to the West, and that it should resolve its foreign policy issues through dialogue.”

Now, he suggested, their estrangement may be beyond repair.

As Mr. Erdogan has tried to contain the fallout, he is blaming domestic conspirators and foreign meddlers, just as he did during last summer’s protests, which began over plans to raze Gezi Park in central Istanbul and convert it into a shopping mall.

“Such accusations are only absurd speculations,” said Ersin Kalaycioglu, a political science professor at Sabanci University in Istanbul. “In Gezi, he accused the Alevis, interest rate lobbies, opposition powers and international power groups for organizing the protests. And now, he’s trying to build the same links with this corruption investigation. What kind of twisted logic is that?”

Hours after a series of dawn raids unfolded at the offices of several businessmen on Tuesday, Mr. Erdogan appeared before a crowd in Konya, a conservative town in the country’s heartland where he draws many supporters. “Some people have guns and weapons, tricks and traps,” he said, “but we have our God and that is enough for us.”

The Gezi protests showed a prime minister deeply involved in local urban planning issues — not surprising to a Turkish public accustomed to hearing Mr. Erdogan tell them how many children to have or what to eat. Similarly, the corruption investigation has laid bare the concentrated nature of power in Turkey.

The inquiry, like the Gezi protests, touches on an issue with deep emotional resonance to the Turkish public, and one at the core of the financial constituency that has built Mr. Erdogan’s power: the dizzying construction in Istanbul and the well-known but rarely acknowledged ties between Mr. Erdogan’s Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party and a new, pious economic elite, anchored in the construction industry, that rose to power alongside him over the last decade.

For residents of this city there are daily reminders, and nuisances, of the power of Mr. Erdogan and his allies in the construction industry: the traffic snarls, the rising cranes and the early-morning jackhammering.

In one section of the city’s historic peninsula, just near the old city walls that once protected the seat of an empire, townhouses sprouted in recent years, providing luxury residences for members of the governing elite and pushing out the Roma community. Nearby, old wooden houses that once housed Ottoman military officers are being refurbished, squatter homes are being demolished and migrants from the southeast are left wondering where they will go.

The mayor of the historic district, called Fatih, and several municipal workers were among those brought in for questioning this week in the corruption investigation, which reportedly involves allegations of taking bribes in exchange for ignoring zoning rules.

“It took Erdogan 10 years, but piece by piece he has taken this city into his hands,” said Mehmet Ali Guler, a garment seller in the district, “pushing us poor fellows out and opening up big luxury spaces to house his own class of rich men.”

NY Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.