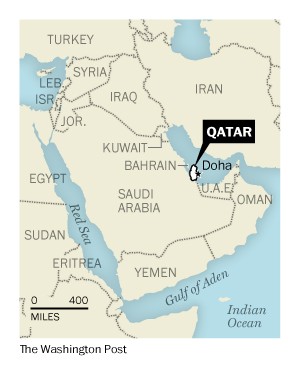

The gas-rich Persian Gulf state, which is slightly smaller than Connecticut, wanted to host world-class sporting events; to build a network of top-tier universities and museums; and to push, tweak and manipulate regional politics to reshape the Arab world to its liking.

The gas-rich Persian Gulf state, which is slightly smaller than Connecticut, wanted to host world-class sporting events; to build a network of top-tier universities and museums; and to push, tweak and manipulate regional politics to reshape the Arab world to its liking.

At the moment, that last priority isn’t going so well.

If 2011 was the tiny state’s year for victory laps — its flag flying high alongside the Libyan rebels, as the revolution there raged with Qatari support; its satellite channel Al Jazeera praised among Egyptian protesters in Tahrir Square; and everybody wanting a bag full of Qatari cash — 2013 has been a year for losses.

Qatar is taking a beating as the Arab Spring revolts, which ushered in Islamist governments in Egypt and Tunisia and empowered upstarts across the region, yield to a reassertion of power by the region’s old heavyweights.

A military coup toppled Qatar’s allies in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the new military rulers have found funding and allies in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates — Qatar’s regional competitors.

Saudi Arabia also has publicly taken the lead on gulf support to Syrian rebels — a cause that Qatar was the first to champion — after the tiny state irked Western and Arab allies by sending aid to hard-line Islamists, analysts say.

In Tunisia, the liberal opposition has sought to vilify the elected Islamist government as Qatari lackeys. In Libya, Qatar is accused of backing Islamist militias at the expense of national unity.

Even the 2022 Soccer World Cup — for Qatar, the ultimate in international validation — has come under scrutiny in recent weeks after Britain’s Guardian newspaper exposed scandalous working conditions for Qatar’s migrant labor force.

The entire region feels “a sense of anger” toward Qatar, said Badr Abdellaty, a spokesman for Egypt’s Foreign Ministry. “And if the Qataris care about their image, it’s important [for them] to revisit this issue and to address it seriously.”

But if the rise in anti-Qatar sentiment has prompted any soul-searching in the upper echelons of the Qatari royal family — or even amongst its citizenry — it is well-hidden here amid the high-rises of Doha.

Qatar’s government is deeply opaque. At the Qatar News Agency, where visiting journalists are required to submit details of their coverage plans and any official interview requests, the media relations staff members said securing an interview with a top official — or any official — would be nearly impossible.

Rumors abound on the periphery of this secretive government that Sheik Hamad Bin Khalifa al-Thani’s abdication as emir in June, and the removal of longtime prime minister Hamad Bin Jasim al-Thani, signified a quiet acknowledgment of defeat.

Rumors abound on the periphery of this secretive government that Sheik Hamad Bin Khalifa al-Thani’s abdication as emir in June, and the removal of longtime prime minister Hamad Bin Jasim al-Thani, signified a quiet acknowledgment of defeat.

Some analysts say the new emir, Tamim Bin Hamad al-Thani, represents a Qatar that is more inwardly focused and less likely to assert itself internationally.

Others — particularly Qataris — say: Don’t be fooled. Qatar may have toned down aspects of its foreign policy, but it’s still evolving and learning how to handle its money and its diplomacy in a region full of heavy hitters.

“A year ago, you were almost looking at a complete regional sweep for Qatar. And that went very wrong,” said one Doha-based analyst, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he has close contacts in Qatar’s security community. “But at the time, it seemed very right.”

Gaining prominence

Hamad, Qatar’s former emir, wanted to put Qatar on the map when he came to the throne in 1995, analysts and Qataris said. And by that metric, he did well.

Hamad took on other Arab world autocracies in 1996 with the launch of the Al Jazeera television network, which introduced to the region a new and unfamiliar form of critical reporting.

He reached out to an unlikely array of global actors, too, playing host to the Palestinian militant group Hamas; Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir; Darfuri, Libyan and Syrian rebels; Iranian diplomats; Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood; and the Taliban. It has been a far-reaching sort of diplomacy that has, at turns, irked Qatar’s more predictable gulf neighbors, as well as Washington.

Qatar hosts one of the largest U.S. military bases in the Persian Gulf and continues to work closely with the U.S. government in support of Syrian rebels and in regional mediation efforts, Qataris close to the royal family said.

But Qatar’s seemingly ad hoc policy on Syria has rubbed Washington the wrong way, analysts said. The United States has “had major issues with the Qataris supporting certain groups and doing their own thing and not being as responsive to U.S. concerns,” said Shadi Hamid, the director of the Brookings Doha Center. “At the end of the day, Qatar does what it wants to do.”

Plenty of ambition

The skyline beyond the 19th-floor window of Hamad al-Ibrahim’s office is a testament to Qatar’s ambition. All of Doha is a construction zone — a landscape of shimmering glass skyscrapers and newly stacked concrete and steel, peppered by armies of yellow cranes and thousands of South Asian laborers.

“I think Qatar mastered the art of catching opportunities in a region full of opportunities,” said Ibrahim, the head of planning and strategic initiatives at the Qatar Foundation, which manages billions of dollars of Qatari charity, development and investment projects at home and abroad.

Brookings’s Hamid said that, put simply, Qatar’s leaders want it to matter. “They want Qatar to be taken seriously,” he said. “They want to have their hands in things.”

But Qatar’s mistake, analysts say, was that it was never careful enough about where it put those hands.

In its rush to oust Syrian President Bashar al-Assad — and earlier, Libya’s Moammar Gaddafi — Qatar has funneled money and weapons to hard-core Islamist groups.

Qatar’s critics say that the tiny state’s chaotic rush to provide aid has upended unity efforts in post-Gaddafi Libya and that its almost indiscriminate support of radical Islamists in Syria is effectively undermining the more moderate Free Syrian Army.

Al Jazeera has come under fire, too, criticized as becoming a mouthpiece for the Muslim Brotherhood. It’s an allegation that few here — including employees of Al Jazeera who spoke on the condition of anonymity — deny.

“Qatar’s name is in the mud,” said David Roberts, a lecturer for King’s College in London who is conducting classes for the Qatari military.

Qatar has presided over “just a complete failure of policy” in Egypt, Roberts said. “That must lead to some kind of re-jig or rethink.”

But foreign analysts say that Doha’s intentions were never as nefarious as their critics claim. More often, they say, Doha’s policies reflected the bold and sometimes haphazard desire of a few powerful men to win friends and influence events, rather than any deep preference for Islamists or even a well-thought-out plan.

“We supported the Islamic states in Egypt and Tunisia because we thought they had a better chance of running the country. And guess what? They won,” Ibrahim said. “Qatar — when they bet, they bet on the right people.”

Qatar’s 250,000 citizens — a minority in a country otherwise packed with foreigners — pride themselves on their unique Qatar brand, which includes their conservatism, which stands in contrast to their rapidly globalizing capital.

Women here wear black cloaks, or abayas, and cover their hair; men wear long white robes, or thobes. Social events, business meetings and political arrangements still often play out in the traditional all-male sitting room of the family home, known as the majlis.

And yet the capital is alive and churning with development 24 hours a day, with new high-rises and shopping malls shooting skyward and Qataris vying for space on the roads in their luxury cars.

The country’s ruling family has managed its gas wealth well, and polls conducted by Qatar University show there is little demand for democratic reform. With a gross domestic product of $103,000 per capita, Qatar is by at least one measure the richest country in the world.

On foreign policy, the attitude has been: “If you have a ton of money, why not try to use it to impact regional events and leave your mark?” Hamid said.

The problem, of course, is that Qatar took that idea a little too far. “I think every day they wanted a new challenge,” said Ibrahim, of the Qatar Foundation. “But you can only do so many things at once.”

Washington Post

File photo: Sheikh Hamad Bin Khalifa al-Thani is shown with his son Tamim the new ruler of Qatar

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.