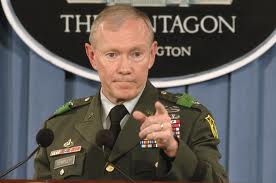

The chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff opened a weeklong visit to the Middle East on Monday for discussions on potential additions of American support to Israel and Jordan, which are both facing border-security challenges from the conflict in neighboring Syria.

The chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff opened a weeklong visit to the Middle East on Monday for discussions on potential additions of American support to Israel and Jordan, which are both facing border-security challenges from the conflict in neighboring Syria.

The chairman, Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, said his talks in Jordan would include an assessment of whether American surveillance aircraft or collaboration on other border-control techniques could help the Jordanians, whose country is the emergency home to tens of thousands of Syrian refugees — and, increasingly, a route for black-market weapons transported both ways across the Syrian frontier.

Syria has accused Jordan of acting as a transit point for weapons supplied to Syrian rebels, an accusation Jordan has denied. In recent days, the Jordanian authorities have detained suspected smugglers, including Syrians, accused of attempting to bring antitank missiles, surface-to-air missiles, assault rifles and other arms from Syria into Jordan — possibly part of an attempt by jihadists in Syria to foment unrest in Jordan as well.

The Pentagon already has deployed air-defense missile batteries in Jordan, along with crewed F-16s to train alongside the Jordanian Air Force in patrolling Jordan’s border and airspace. A few hundred American military planners, including communications experts and logisticians, also are in Jordan.

In some of his most extensive comments on the Syrian crisis to date, General Dempsey noted that cooperation flows both ways, in particular as the United States has benefited from local intelligence efforts tracking Syrian chemical weapons.

“Probably the single point of greatest collaboration with Israel, Jordan and the United States is in identifying the potential chemical threat, its location, trying to determine the intentions of the Syrian regime,” General Dempsey said.

The Syrian government’s chemical munitions, he said, still are moved “from time to time” around the country, likely a reflection of the government’s concerns that if the weapons remained in one place they could be located and seized by rebels. “It appears the regime is moving it to secure it,” General Dempsey said. “But that could change.”

Early in the Syrian crisis, President Obama declared the use of chemical weapons to be a “red line” leading to American action. That talk has faded as both the Syrian government and the militias have been accused of limited use of chemical arms.

The most feared outcome would be for the government’s large stockpile of chemical arms to be seized by radical groups amid the chaos, and there appears to be a tacit assent for the Assad government to do all it can to secure those weapons, even if that requires shifting them around the country.

In statements to Congress, General Dempsey has warned of the costs and risks of direct American military intervention in the Syrian civil war, and in a discussion with correspondents here on Monday he made the administration’s case for seeking “to influence through the support of a moderate opposition and, importantly, through increasing the capabilities of our partners.”

He cited cooperation with Israel, Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon and even Iraq, and described expanding American efforts to identify and assist moderate elements of the rebel movement.

“I am very concerned about the radical element of the opposition, and I am concerned about the potential that extremist ideologies will hijack what started out to be a popular movement to overthrow an oppressive regime,” he said.

He acknowledged that radical militias, which assumed an ascendant role in the civil war about six months ago, remained a powerful force with some of the best fighters on the rebel side. But in the last six months, he said, the United States has increased its ability to identify moderate opposition leaders, and to begin communicating with them in substantive ways.

Even so, he acknowledged that battlefield necessity may require radical and moderate militias to cooperate for tactical gains against the Assad government — a convergence that would complicate American and allied policy making.

“It doesn’t surprise me that from time to time they collaborate with each other,” he said. “What we have to be alert for are opportunities to convince the more moderate aspects of the opposition that Syria will be a far better place if the moderate opposition dominates in the end game.”

But the general’s immediate prognosis for Syria was grim, and he said any planning for supporting the opposition, assisting refugees and strengthening allied security forces required a much longer view than has informed much of the policy debate in Washington.

“The issues that are fueling the conflict in Syria will not be resolved in the short term, even if the Assad regime were to fail tomorrow,” he said.

“This is a regional conflict that stretches from Beirut to Damascus to Baghdad,” he said. “It is the unleashing of historic ethnic, religious and tribal animosities that will take a great deal of work and a great deal of time to resolve.”

NY Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.