A currency surging in value at a breathtaking rate this week belongs to no nation and is issued by no central bank. It can be used to buy gold in California, a hamburger in Berlin or a house in Alberta. When desired, it can offer largely untraceable transactions.

A currency surging in value at a breathtaking rate this week belongs to no nation and is issued by no central bank. It can be used to buy gold in California, a hamburger in Berlin or a house in Alberta. When desired, it can offer largely untraceable transactions.

The coin in question now has a global circulation worth more than $1.4 billion on paper. Yet almost no one, it seems, knows the true identity of its creator. In the United States, this mysterious money has become the darling of antigovernment libertarians and computer wizards prospecting in the virtual mines of cyberspace. In Europe, meanwhile, it has found its niche as the coinage of anarchic youth.

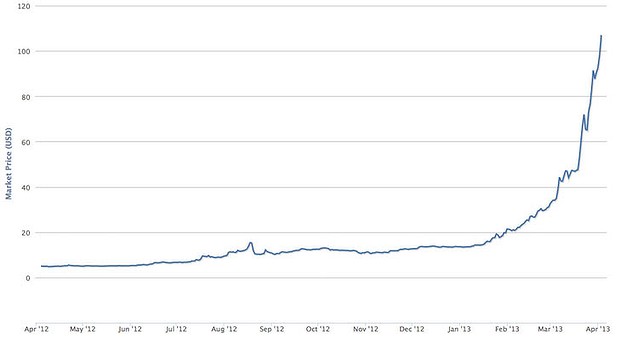

The currency is bitcoin, a kind of cyber-money initially traded among hackers and cryptologists, and increasingly traded on Web sites and exchanged for goods and services. Two years ago, one bitcoin was worth less than $1. Two months ago, the price for one unit surged above $20 on a proliferation of cyber-exchanges from Tokyo to Moscow. A sudden burst of new interest sent its value soaring to a record $147 on Wednesday.

It has since fallen back after a series of hacker attacks. Yet, as of Thursday, bitcoin was still trading above $130.

Will all that crash and burn in a cyber-version of a financial bubble? Critics say it quite possibly will. Will authorities — already concerned about the use of bitcoins to buy drugs and launder money online — step in to regulate it? There are signs that may already be happening. But for now, its diverse group of users ranging from the Free State Project and WikiLeaks to environmentalists and professional gamblers, call its surge a revolution in “financial free speech.”

For Jonathan Harrison — a former gold trader who ditched his London flat to join a group of virtual currency obsessives living in a dilapidated commune on the wrong side of Waterloo Station — what matters most is a sense that bitcoin is making him a fortune.

Some call it the purest form of capitalism: a version totally unfettered by monetary policy and politically driven economics. On a recent afternoon, Harrison constantly checked the value of his holdings in bitcoins and other cyber-currencies such as litecoin on his glowing smartphone. In less than 20 minutes, his portfolio’s value had surged by about 7 percent.

“Some people say it’s anticapitalist, but it’s more nonconformist,” Harrison said. “It can’t be manipulated by governments, changed by monetary policy. I call it digital gold.”

Mysterious origins

In January 2009, Satoshi Nakamoto unveiled bitcoin to a mailing list of computer super-geniuses. He (or she, or them — Nakamoto is a pseudonym for a programming whiz or whizzes whose identity remains one of the great mysteries of hackerdom) effectively put a free software program on the Internet and invited the group to form a network of bitcoin “miners.” They could excavate bitcoins by using computers to solve complex mathematical puzzles, with units of the cyber-currency seen as a reward for the electricity spent on the algorithms.

In January 2009, Satoshi Nakamoto unveiled bitcoin to a mailing list of computer super-geniuses. He (or she, or them — Nakamoto is a pseudonym for a programming whiz or whizzes whose identity remains one of the great mysteries of hackerdom) effectively put a free software program on the Internet and invited the group to form a network of bitcoin “miners.” They could excavate bitcoins by using computers to solve complex mathematical puzzles, with units of the cyber-currency seen as a reward for the electricity spent on the algorithms.

Nakamoto seemingly emerged from nowhere a year earlier, uploading a white paper on bitcoin to an obscure e-mail discussion group. The writings suggested political motivations — a response to a global financial crisis in which Western governments reached into the banking sector as never before. But Nakamoto also showed little interest in promoting bitcoin beyond an inner circle of global geekdom.

In the 1990s and 2000s, various visionaries attempted to launch cyber-currencies with little success. Yet Nakamoto succeeded where others failed through the elegance of bitcoin’s design. More bitcoins are created all the time. But over time, fewer and fewer will be generated. The finite number — bitcoins will max out at 21 million by 2140, compared to the roughly 11 million in circulation today — makes them a commodity that increases in value as more and more users fuel demand.

To avoid counterfeiting, bitcoins are accounted for on public ledgers. Holders of bitcoins — which are stored using electronic “wallet” software downloaded from the Internet — are kept anonymous unless they choose to disclose their identities. Yet there is no centralized authority that regulators could home in on to shut the system down. Though government- and bank-free, the users pay a certain price for that freedom. U.S. bank deposits, for instance, are insured up to $250,000 by the FDIC. But this week, when hackers struck bitcoin wallet provider Instawallet, the company issued a statement saying it would refund clients holding more than 50 units only on a “case-by-case and best-effort basis.”

Nakamoto seemed to vanish more than a year ago, leaving other developers to advance the technology. A year later, initial waves of publicity and word of mouth created a surge in value that sent the price of one bitcoin soaring from less than $5 to almost $30.

There were now two ways of getting bitcoins — mining them yourself or, more commonly, buying them from current owners using real-world currency. However, after a series of high-profile hacker attacks — including a hit on the computers at Mt. Gox, the Tokyo-based exchange site that is the cyber-currency’s largest — its value collapsed, falling back below $10 and increasing only modestly until a few months ago. Another wave of attacks hit the exchange house this week but have thus far not caused equal damage.

No one knows what, exactly, is behind the currency’s staggering climb that started earlier this year and accelerated in recent weeks. Some cite a change in the network’s programming in December that cut the number of bitcoins released each day. Others say new interest from Russians and others looking for safe havens after bank account seizures in Cyprus is behind the climb.

Bitcoin promoters credit new interest by venture capitalists. Yet Wall Street analysts who follow bitcoin say there is still no indication that major investors are seriously dabbling in them. Critics say those paying hefty fees for bitcoins are investing in a ghost currency whose value is fictional.

“What’s behind that billion-dollar value? Nothing, except some people would claim a billion dollars worth of burned electricity,” said Ben Laurie, a software engineer and visiting fellow at Cambridge University.

Though critics warn current buyers will themselves be burned if the price collapses, bitcoin’s rise already has early merchants ruminating about what might have been. George’s Famous Baklava in New Hampshire, for instance, sold a pan of dark chocolate pastry online for 14 bitcoins in 2012 — a sum worth about $1,890 today. “I’m already looking back on that and smiling,” the company’s owner, George Mandrik Skouras, wrote in an e-mail.

A growing marketplace

The antiestablishment nature of bitcoin has also made it the preferred currency of antigovernment activists. Harrison, the bitcoin trader, for instance, first learned about the currency after watching a viral video made by Amir Taaki, a former online poker player turned freelance software developer who now organizes bitcoin conferences. Taaki’s conferences have drawn interest from everyone ranging from money laundering experts to the likes of Cody Wilson, the American crypto-anarchist who is pioneering 3-D printing technology to create plastic guns.

The marketplace that accepts bitcoins is small but growing. At Room 77 in Berlin, you can use your smartphone to digitally pay for a hamburger in bitcoins. More often, you can shop online for a range of items including, as bitcoin enthusiasts admitillegal drugs.

Once the province of hobbyists rigging together off-the-shelf computer parts, bitcoin “mining” is also rapidly evolving. The math puzzles that award bitcoins have become harder as more and increasingly powerful computers mine them.

It has led cyber-thieves to hijack computers via viruses that help them mine bitcoins. Legal miners such as Bennett Hoffman, a California-based bitcoin enthusiast who once hunted them on his gaming computer, are joining up with business partners to invest in new professional bitcoin-mining machines costing $30,000 each.

“Obviously there’s always going to be a ton of risk involved,” Hoffman said. “I just really like the idea of bitcoin.”

Last October, the European Central Bank issued areport on the topic. Last month, a branch of the U.S. Treasury concerned with money laundering issued guidance to online exchanges in the United States, warning that they must report large cash transactions and suspicious activity on their systems.

“In a way it is like . . . Monopoly money being used rather than your respective currency, not knowing who owns the bank and who is the dog, the car, the top hat or thimble,” said Rusty Payne, a spokesman for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency. “Bitcoins are virtually untraceable.”

Washington Post

What is a bitcoin?

The virtual currency enables direct payment over the Internet between two individuals by skipping the middle man, such as a bank or credit card company. Bitcoin transactions — with fees that are much lower than what financial institutions charge — rely on cryptography to prevent double spending, counterfeiting or theft.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.