By Nana Asfour

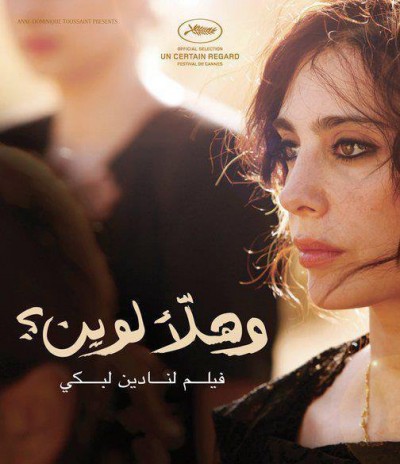

The New Directors/New Films series at MOMA opened last week with the story of a group of Muslim and Christian women in a remote village who band together to stop their hotheaded men from engulfing their community in yet another war. The film, titled “Where Do We Go Now?” and directed by Nadine Labaki, set box-office records in Lebanon since opening there in September and received a standing ovation at the festival’s première.

The New Directors/New Films series at MOMA opened last week with the story of a group of Muslim and Christian women in a remote village who band together to stop their hotheaded men from engulfing their community in yet another war. The film, titled “Where Do We Go Now?” and directed by Nadine Labaki, set box-office records in Lebanon since opening there in September and received a standing ovation at the festival’s première.

I had seen the film a few days earlier, but I still found myself looking forward to watching it again. I was also curious to see how others would react to it. The film seemed so specifically Lebanese—in its theme of religious strife, in its locale, in the interactions between the characters—that I wasn’t sure if I was relating to it because I myself am Lebanese and had grown up, like Labaki, in the Lebanese civil war (it went on from 1975 until 1990), or if I was responding to it as a general moviegoer. The applause for the film at MOMA was reassuring confirmation that, like Labaki’s début film “Caramel,” her latest effort entirely transcended its local subject matter and setting.

Labaki is one of a relatively long list of Lebanese female directors whose films have been show in film festivals in New York and elsewhere. But none have had the wide appeal—at home and abroad—of Labaki, who, with merely two films, has already established herself as an important female Arab filmmaker. As in “Caramel” (2007), which centers on a hair salon in Beirut and its women workers and clientele, Labaki stars in the new film and has a budding romance with a fellow Lebanese. And like “Caramel,” “Where Do We Go Now?” follows female friends who belong to different religions and are of different ages, young and middle-aged. But whereas “Caramel” was set in post-civil-war Beirut and purposefully made no allusions to the country’s turbulent political atmosphere, the threat of war is the driving force of the new film’s narrative.

“Where Do We Go Now?” was inspired by disturbing events in Lebanon. “On May 7th, 2008, fighting broke out between two opposing parties,” thirty-eight-year-old Labaki, told me when I reached her by phone recently. “Beirut turned into a war zone in a matter of hours. We were stuck at home, the roads were blocked. I was watching TV and saw people with masks, weapons, and grenades. I thought, Is that really possible? Could we be here yet again? And go into civil war one more time?”

That same day, Labaki had learned she was pregnant. “I thought if my son was now eighteen years old and he was tempted to join the fight and take the burden of protecting his family—because it’s always tempting especially for young men—what would I do as a mother to stop him?”

Her cinematic manifestation of how to handle such a situation is as humorous as it is tragic. In the beginning of the film, the young boys set up a TV in the village’s main square. It’s the only TV in town and the entire community gathers to watch it. A Lebanese female presenter, in a skimpy top and tight jeans, appears on the screen. Her outfit, which is very common in Lebanese shows, is a stark contrast to the village’s demurely dressed women. The men respond approvingly, hissing at the TV.

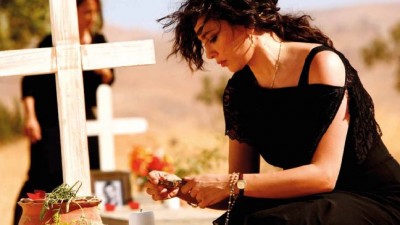

Soon thereafter, the village’s women climb high up in the mountains in the dead of night to unplug the TV connection. It’s not the men’s exposure to sexy women or racy films that they are trying to prevent. They don’t want them to watch the news. Fighting between religious factions has broken out in other parts of the country and the women worry that, upon hearing this, their men will feel inspired to start killing each other once more. Having already lost many loved ones in previous, religion-motivated wars, they are not about to let it happen again. So they fake miracles (the Virgin Mary is weeping and demands peace in the village), they hire Eastern European showgirls from Beirut (the city is full of them) to spy on the men and divert their attention, they drug their husbands and sons, and, after a fatal incident, they resort to an unthinkable (and, as Labaki noted during the première, given that this is Lebanon) unlikely solution. And yet, her “fable,” as Labaki calls her film, remains a powerful indictment of religious conflict and a charming celebration of female resistance.

Soon thereafter, the village’s women climb high up in the mountains in the dead of night to unplug the TV connection. It’s not the men’s exposure to sexy women or racy films that they are trying to prevent. They don’t want them to watch the news. Fighting between religious factions has broken out in other parts of the country and the women worry that, upon hearing this, their men will feel inspired to start killing each other once more. Having already lost many loved ones in previous, religion-motivated wars, they are not about to let it happen again. So they fake miracles (the Virgin Mary is weeping and demands peace in the village), they hire Eastern European showgirls from Beirut (the city is full of them) to spy on the men and divert their attention, they drug their husbands and sons, and, after a fatal incident, they resort to an unthinkable (and, as Labaki noted during the première, given that this is Lebanon) unlikely solution. And yet, her “fable,” as Labaki calls her film, remains a powerful indictment of religious conflict and a charming celebration of female resistance.

Labaki has proven herself to be a natural storyteller (although, it should be noted, that she gets considerable help from her male writing partners), and a filmmaker with a propensity for creating strong female characters who are both funny and provocative. The women in “Where Do We Go Now?” are sharp-tongued; they tease each other about their weight and exchange mocking comments about their husbands’ virility. But the bond between them is strong and unshakeable. Asked whether she chooses to focus on women because of some kind of feminist agenda, Labaki says, “I’m not on a mission to empower women.” She insists that her subject matter is merely a reflection of what comes naturally to her.

For me, watching the women interact onscreen was like being transported back to a kitchen scene from my own childhood in Beirut—the female gatherings, usually of relatives and neighbors, seemed to always take place in the kitchen. The acting is so natural that I was surprised to discover, upon speaking to the director, that the women (and men) were non-professional actors. “I like to have the impression that whatever is happening is true,” she told me. “Even as the filmmaker and as an author, I need to believe that this person is not acting. I want to believe that that person would have reacted in that way in that situation.”

As a director, Labaki has shown considerable audaciousness. One of the characters in “Caramel” was a lesbian; another underwent surgery to conform to traditional values that require a woman to be a virgin for her wedding. The subject matter of her latest film is no less incendiary. “Religion is a very delicate subject in Lebanon,” she told me. “You have to know how to say things in a very delicate way in order to be accepted.” She earns that acceptance by practicing a form of self-censorship. “Somehow it has become a part of my nature. Self-censorship has become a part of me,” she says. “I think because we live in a place where community is very important, family is very important, you feel the weight of how people look at you. Even though I might seem very modern and very liberated, I still have a lot of issues to deal with. I’m scared of how people look at me.”

Despite these fears, Labaki is impressively strong-willed. “I have learned to do what I want without hurting anyone,” she told me. “I’ve learned how to get away with it, with everything. I’m getting away with what I’m trying to do on film but also in my own way.”

The New Yorker

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.