Beirut, Lebanon: In his almost 11 years in office, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has brought about some remarkable changes to a country formerly run by his notoriously ruthless father, fueling perceptions that he is at heart a reformer, albeit one who has been held back by hard-liners intent on preserving the status quo.

Under his rule, Syria has opened its doors to foreign investment and private ownership. Cellphones, Internet service and satellite TV have proliferated. The capital, Damascus, has been transformed from a sleepy socialist backwater into the beginnings of a thriving modern capital, with shiny glass offices, European fashion outlets and trendy cafes serving flavored lattes to a hip new elite.

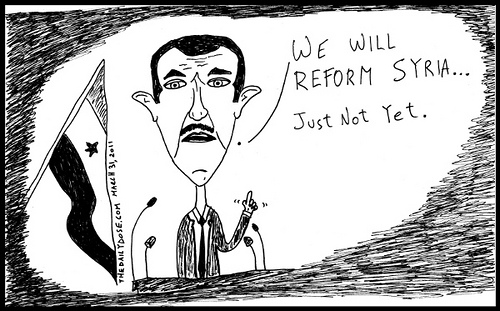

Yet in all those years, the younger Assad has implemented not one measure that would relax the ruling Baath Party’s 48-year-long hold on power, lift the draconian laws that enable the security forces to operate with impunity or ease restrictions on free speech.

Now, with the Syrian security forces escalating a brutal and bloody effort to suppress an almost nationwide uprising, it may be too late for Assad to salvage what little remains of his reputation as the thwarted reformist waiting only for a chance to liberalize his country.

Now, with the Syrian security forces escalating a brutal and bloody effort to suppress an almost nationwide uprising, it may be too late for Assad to salvage what little remains of his reputation as the thwarted reformist waiting only for a chance to liberalize his country.

On Sunday, the army sent tanks into the southern town of Tafas, according to Wissam Tarif of the human rights group Insan. In Homs, he said, 14 people were killed by sharpshooters. But with communications to many parts of the country severed, it was impossible to draw a clear picture of conditions inside the half-dozen or so towns surrounded by the military, Tarif said.

Assad’s “reaction to the demonstrations has been the reaction of a dictator,” said Radwan Ziadeh, a Syrian human rights activist who is a visiting scholar at George Washington University’s Institute for Middle East Studies. “Even if he dramatically changed his mind and announced reforms now, I don’t think anyone would believe him.”

Cultivating his image

Assad has assiduously cultivated the reformist image since he ascended to power in 2000 at age 34, promising a new and more open Syria. With his youth, his British training as an eye doctor and his elegant British-born wife, Asma, he presented a starkly different figure compared with his somewhat thuggish father, Hafez, a military officer, and the region’s other aging autocrats.

It’s an image that many in the international community have cited in justifying their hesitancy to call directly for Assad’s ouster or to include him in sanctions, despite more than seven weeks of bloodshed in which human rights groups say more than 700 people have been killed.

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton called Assad “a reformer” during the early days of the demonstrations, though she later said she was referring to the opinions of others. Even after Syrian tanks rolled into the town of Daraa in a clear signal of the regime’s intent to crush the uprising by force, British Foreign Secretary William Hague said Assad should be given a chance.

“You can imagine him as a reformer,” he told the BBC. “One of the difficulties in Syria is that President Assad’s power depends on a wider group of people, in his family and in other members of his government, and I am not sure how free he is to pursue a reform agenda.”

That perception also lingers in Damascus, where residents have not joined anti-government demonstrations in any significant number. There, rumors are swirling that Assad’s hands are tied, perhaps by his more ruthless and reputedly erratic brother Maher, who heads the army unit leading the crackdown, or perhaps by his powerful mother, Anisa, who some say is keeping her older son at home in his palace while unleashing other family members to quell the revolt.

Yet at no point in the past 11 years has a clear picture emerged of which regime members may be holding Assad back, said Andrew Tabler, a fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, who was among those initially convinced of Assad’s reformist credentials during the eight years he lived and worked in Syria, some of them for Asma Assad’s charities.

“We’ve heard all the time that the old guard was holding him back, but we’ve never heard who the old guard was or seen evidence of them,” he said. “You’d have a conversation with him, and he’d say what you wanted to hear, but after that it doesn’t happen.”

In the first months of Assad’s rule, there was a brief flourishing of freedoms known as the Damascus Spring, followed by a swift crackdown, which gave rise to the narrative that Assad was being held in check by hard-line holdovers from his father’s regime.

But Theodore Kattouf, who was the U.S. ambassador to Syria from 2001 to 2003, suspects the quickly curtailed display of tolerance had more to do with Assad’s inexperience than his inclinations. Although regime old-timers may have helped nudge him back on track, Kattouf said, “he was never a true political reformer.”

“What he intended to do was reform within the existing system. He never intended to truly change the political framework in which his father ruled.”

Since then, the president has cemented his authority by surrounding himself with members of the younger generation of Assad clan members, who have filled key positions in the security agencies and in the new economy.

Among them is Maher, the brother, who heads the powerful Republican Guard. A maternal cousin, Rami Makhlouf, secured the license for Syriatel, the biggest mobile phone company in the country, while Makhlouf’s younger brother Hafez is in charge of the Damascus branch of the intelligence services. Another cousin, Atif Najib, was in charge of Daraa, where the revolt first gained momentum.

“Ultimately, this is a family affair,” said Joshua Landis, an associate professor at the University of Oklahoma who writes the blog Syria Comment. “And all the signs are that the family is sticking together, because they know they’re going to have to live together or die together.”

There’s also no question that Assad is in full control of the family, said Ayman Abdel Nour, who served as Assad’s adviser from 1997 to 2004 before he turned against the regime and moved to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates. “It’s him, and only him, and the family is behind him,” Abdel Nour said. “He is the one in full charge, and he is the one making the decisions.”

A widespread revolt

Meanwhile, Assad has given no indication that he is prepared to address the unrest by meeting protesters’ demands. One of his only concrete promises, to lift the 48-year-old state of emergency, was implemented the day before Syrian troops fatally shot 112 protesters, Ziadeh said, adding that this undermines any notion that reform is seriously on the agenda.

Yet as the violence escalates, the revolt has spread, reaching into towns and villages in almost every corner of the country. Demonstrators who initially confined their demands to reform are now calling for the toppling of the regime.

And even in Damascus, where many still cling to the notion that Assad’s reformist inclinations are being cramped by others, people are starting to question the levels of force being used, said a Syrian academic and commentator who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the subject.

“Bashar is bowing to what’s going on, so he’s part of it,” he said. “That makes him responsible, doesn’t it?”

By Liz Sly,

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.