A top White House aide delivered a personal letter from President Obama to Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah on Tuesday, as the administration moved to calm tensions between the two countries over how to respond to upheaval in the Arab world and deal with their mutual adversary in Iran.

A top White House aide delivered a personal letter from President Obama to Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah on Tuesday, as the administration moved to calm tensions between the two countries over how to respond to upheaval in the Arab world and deal with their mutual adversary in Iran.

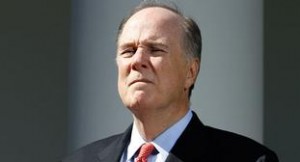

The hastily arranged visit to the kingdom by national security adviser Thomas E. Donilon came less than a week after Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates made the same trip. While administration officials confirmed the delivery of Obama’s missive, they declined to specify its contents.

Neither government denies that there has been a divergence of views between the entrenched, conservative monarchy and the administration, which is struggling to balance its substantial interests and alliances in the region with its desire to see democratic reforms.

The stakes are high for both sides, perhaps higher for Obama.

Saudi Arabia, in addition to being the world’s largest oil exporter and the site of the Muslim world’s holiest sites, is the leading U.S. regional partner on counterterrorism matters. An extensive bilateral intelligence and law enforcement infrastructure has been established over the past decade. A pending $60 billion arms deal with the Saudis is the largest in U.S. history.

A senior Saudi official said the back-to-back U.S. trips were less “fence-mending” than consultations on “how do we move forward . . . given all the things that are happening, in ways that best protect our interests.”

While the administration sees democratic potential in the Arab spring, the Saudis are feeling an ominous chill from all points of the compass — Bahrain to the east, Yemen to the south, Egypt to the west and Iraq to the north. They have also seen signs of internal unrest, with minor Shiite demonstrations in the eastern part of the kingdom in recent weeks.

Saudi leaders were furious last month when the administration criticized their deployment of troops to Bahrain, the small island nation in the Persian Gulf whose Shiite majority has taken to the streets to demand more political representation from Sunni rulers. U.S. calls for political dialogue were interpreted as a naive response to what the Saudis see as a clear case of interference by Iran’s Shiite theocracy.

Bahrain is the “reddest of red lines” for the Saudis, said a member of the Majlis al-Shura, the consultative council that advises Abdullah on a range of foreign and domestic issues.

Beyond Bahrain, the Saudis were stunned at Obama’s rapid abandonment of Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, a decades-long ally. They have been dismayed by what they see as Obama’s failure to seize the initiative in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. They also consider Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki little more than a stooge for Iranian interests, and were disappointed in the administration’s support for his second term in office against Saudi advice.

“I don’t want to pretend we haven’t had some differences,” said a senior U.S. official who was not authorized to discuss the situation on the record. “There are some things we need to work on.”

While the administration shares the Saudi concern about Iranian expansionism, it also believes that the Saudis have developed a dangerous fixation on Iran’s role.

“It can become a self-fulfilling prophecy,” the administration official said. “If you see every Shiite as an Iranian agent, that could very well turn out eventually to be the case.”

Underlying the current tensions is Saudi Arabia’s long-standing concern that it “has been taken for granted by the United States,” said another member of the Shura, part of a group that visited Washington last week.

The Saudis consider themselves “the voice for moderation and stabilization in the Middle East,” he said, and resent the U.S. implication that the administration is more attuned to threats such as Iran, or that the Saudi monarchy needs to move toward its own reforms at a faster pace than it believes is wise or necessary.

Some foreign policy experts in this country agree that Obama needs to pay more attention to the relationship. The Saudi king needs to know “that the president will provide a secure safety net of support, rather than undermine him” in the event of trouble in the kingdom, Martin Indyk, the director of the Brookings Institution’s foreign policy program, wrote in The Washington Post early this week.

Saudi uncertainty was reflected in a visit to Pakistan last month by Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the head of the Saudi National Security Council.

Until the mid-1990s, Pakistan maintained a division of troops in Saudi Arabia, and it has long been a recruiting ground for Persian Gulf security forces. Although Bandar made no official request, he was assured of help if needed, a senior Pakistani official said. “We hold the Saudis so close,” the official said, “we have to really help them if there is a need.”

But others are more dismissive of Saudi concerns. “Our friends are mad at us because we said Mubarak had to go,” Sen. John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) said Tuesday at the U.S.-Islamic Forum, a conference in Washington jointly sponsored by Brookings and the government of Qatar. “We didn’t say that . . . the Egyptian people did,” Kerry said. “We acknowledged a reality.”

“For leaders worried about their regimes, royal families and governments,” Kerry said, “this is an opportunity to adjust to how they stay in power.” WP

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.