By Roya Hakakian

Ever since the crowds flooded into Tahrir Square, I’ve begun talking to the living-room television. “Drop that hand!” I shouted at the raised fist of a pro-Mubarak thug a few days ago. On Friday, watching the fireworks over the skies of Cairo, I enviously mumbled: “How come we didn’t do that?”

We, as in the young Iranians who flooded Tehran’s own equivalent of Liberation Square, Azadi, on the same exact day 32 years ago. I was 12 at the time, but the events of that year remain my existential paradox, my life’s most cherished trauma.

The pundits now breezily call Iran’s 1979 revolution “Islamic.” But at the time, religious and secular, villagers and urbanites, educated and illiterate, all equally angrily, were marching in the streets and demanding the removal of the Shah. Iran’s future was as unknowable then as Egypt’s future is now.

Comparisons between Iran and Egypt abound and the guessing goes on as to what number Egypt’s needle truly points on the Iranian time scale: 1979, or 2009 — the year the Green movement took the streets of Tehran. One of the dozen exuberant wallposts on my facebook page on Friday reads: “Egypt did it in 18 days. Iran will do it in a week!”

Egypt is not Iran. No two histories or nations, no matter how much they have in common, are interchangeable. But movements striving for common democratic goals have consistently exchanged the lessons of their struggles to inform and warn their comrades elsewhere against the pitfalls and to also facilitate a change of their own. The fear that fleeing dictators exude is very potent.

Today’s Egyptian democratic forces ought to heed the errors of their Iranian counterparts from 1979. Above all because those errors were, by and large, not rooted in malice or ignorance but in good intentions. And also because their sinister effects did not reveal themselves until long after the euphoria had ebbed and the crowds had left the squares to resume their lives once again.

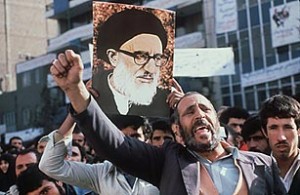

The first misstep of the Iranian secular movement came as early as 1978, when they blindly embraced a union with the religious opposition, having been perfectly disarmed by them. When the exiled Ayatollah Khomeini said that he had no political ambitions, and that, once the Shah was gone, his only wish was to hunker down with a Koran at a seminary in Qom, everyone believed him. When he spoke against the violations of human rights in the Shah’s prisons, the intellectuals called him their homegrown Gandhi. When he talked of gender equality and women’s rights, he was hailed unequivocally as if he’d been the heir to Betty Friedan. Before rising to power, the religious opposition to the Shah, headed by the Ayatollah, told Iranians what they wished to hear and they believed everything they heard.

The few who were smart enough not to believe the Ayatollah made the common mistake smart people often make: they underestimated the intelligence of others. They were confident that they could outmaneuver the Ayatollah. The Western-educated, stylishly-suited secular leaders assumed themselves far too sophisticated to be outwitted by the plainly-dressed provincial clerics.

They also did not realize that keeping the movement peaceful and nonviolent was detrimental to keeping themselves relevant and credible. Once the army had opened fire and the first victims had fallen, the religious co-opted the movement. The seculars had no substantive plans for retaliation or political comeback in light of a military attack. But the shedding of blood was the cue for the religious to enter the stage and move into the spotlight. When it came to death, the religious had a full lexicon and complete repertoire of rituals to balance the strategic shortcomings of their secular counterparts. After all, death and all of its conceptual by-products, especially martyrdom, had always been the proverbial bread-and-butter of the clergy, the spring of their livelihood.

As time passed, it quickly became clear that the easiest part of the revolution was the very thing that had seemed the hardest all along: the overthrow. Navigating the future was a most daunting task for which individuals who had spent decades dreaming of the Shah’s fall had never planned for. With the revolution’s victory, the movement, overcome by joy, lost its direction. They became overambitious and gave into globalistic hubris. Freedom for Iranians, employment and education for the youth, or the implementation of civil liberties were no longer enough. Those bête noires, evil Uncle Sam and his bastard child, Israel, had to also be uprooted. Once they shifted their focus from domestic issues, they had empowered the religious once again. Within months after the fall of the Shah, Iraq attacked Iran and the Ayatollah dragged the nation into a decade of destruction because, he argued, the quickest way to annihilating the world’s two greatest evils was through conquering Baghdad en route to Jerusalem. Tehran, and its residents, did not satisfy the grand agenda.

Iranians allowed themselves to be manipulated. The regime cowed them into making concessions by preying on their fears — of the return of the Shah, or the staging of a coup by his loyalists within the army. Instead of remaining uncompromising on the issues that defined them, they made compromises and bought into piecemeal, gradual, interim promises. Lest monarchy return, women were told to defer their demands for equal rights. Then in 1979 the U.S. embassy in Tehran was seized which the Ayatollah celebrated as a day second only to Feb. 11, the date of his revolution. Of course, he did. The seizure of the American embassy gave the Islamic radicals the ammunition they needed to conduct their assault on the hard-won and fledgling civil liberties in Iran because, the manipulative reasoning went, there was no telling how the angry Americans were going to infiltrate and avenge themselves on the nation.

In the end, the religious proved too smart to be outwitted by the secular. It made no claim to power until it had fully seized it — a quest fueled by bloodshed and extraterritorial ambitions. Let us hope that the new, wired generation of Egypt will remain as vigilant in seeing their victory through as they had been in bringing it about.

Roya Hakakian is the author of Journey from the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran (Crown 2004) and the forthcoming Assassins of the Turquoise Palace (Grove/Atlantic Press 2011).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.