Omar Suleiman, Hosni Mubarak’s intelligence chief and now his vice-president, is the keeper of Egypt’s secrets, a smooth behind-the-scenes operator who has been intimately involved in the most sensitive issues of national security and foreign policy for close to 20 years.

Omar Suleiman, Hosni Mubarak’s intelligence chief and now his vice-president, is the keeper of Egypt’s secrets, a smooth behind-the-scenes operator who has been intimately involved in the most sensitive issues of national security and foreign policy for close to 20 years.

As mass protests continued in Cairo and elsewhere, this discreet spymaster faced intense scrutiny both at home and abroad as he holds the key to the political future of the Arab world’s largest country. Famously loyal to Mubarak, Suleiman looks likely to determine his fate.

Late on Monday he went on TV to announce that he had been ordered by the president to tackle “constitutional and legislative reforms” and, crucially, to include opposition parties in the process. That looked like an attempt to defuse the crisis by starting a dialogue it is hoped will ensure the survival of the regime.

Suleiman’s appointment as vice-president on Saturday carried two significant messages: for the first time since coming to power in 1981 Mubarak had decided on a successor, squashing speculation it would be his son Gamal; and that successor has the full confidence of the military.

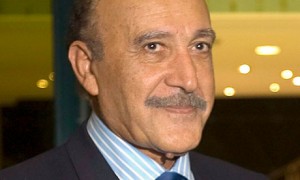

Suleiman, 74, is bald and mustachioed and despite his military bearing has a penchant for dark suits and striped ties. Acquaintances remark on his exquisite manners – as well as a taste for good cigars supplied by ever-attentive aides. “Suleiman is an imposing man,” recalls former British ambassador David Blatherwick. “He’s pretty wily, very polished and extremely intelligent. People are scared of him, for obvious reasons.”

In 1995, two years after taking over Egypt’s General Intelligence Service (the mukhabarat), he saved Mubarak’s life during an assassination attempt in the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa, having insisted his boss travel in an armoured car.

He also played a key role in defeating the insurrection mounted by armed groups such as Islamic Jihad, some of whose members went on to found al-Qaida. In the mid-1990s he is said to have worked with the CIA on handing over wanted militants, a practice that continued as “extraordinary rendition” after the 9/11 attacks. For 30 years before that Suleiman served in the army, fighting in Yemen and in the 1967 and 1973 wars against Israel, rising to be director of military intelligence. He was trained in the Soviet Union — and later on in the US.

He believes fervently in the military and its view of Egypt’s core national interests. This consummate insider is “the second most powerful man after Mubarak”, in the words of commentator Hisham Kassem.

“Suleiman is a decent man, not a thug,” one old acquaintance says. “He’s very pragmatic, a subtle and smart guy. I don’t think he has personal ambition other than to try to hand on the underpinnings of the regime to a worthy recipient.”

In recent years one of Suleiman’s biggest preoccupations has been dealing with the volatile Palestinian file, mediating between the western-backed Fatah movement and the Islamists of Hamas – a group with special resonance in Egypt because of its control of the Gaza Strip and its links to the banned Muslim Brotherhood, which he is said to loathe. The Israelis trust him, not least because of his open line to the president. “Suleiman doesn’t pull the strings in Egypt,” a well-placed source told Ha’aretz. “He pulls the ropes.”

He has also been involved in the tangled affairs of Sudan and has mediated between rebels and the government in Yemen. The US and other western governments still see him as a safe pair of hands, and are now in intensive contact with him and other top military men as Egypt’s future hangs in the balance.

The turbulent events of the last 10 days have thrust the spy chief into unaccustomed limelight – and the challenge of a lifetime of dedicated service. Suleiman is one of a rare group of Egyptian officials who hold both a military rank (lieutenant general) and a civilian office as a minister. Like other members of the military top brass, he is profoundly hostile to the Muslim Brotherhood, who he has described as “liars who only understand force”. But the political manoeuvring to manage the crisis will almost certainly involve dealing with them as the largest opposition group in the country.

“Suleiman never had a role in national politics before,” warns a former colleague, “though he would have been consulted. “The question now is how he will manage in this new situation.” Guardian

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.