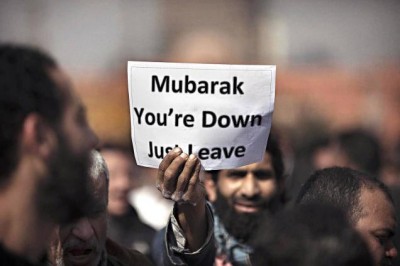

Pulling the plug off the Internet appears to the first resort of a regime that faces widespread popular protests.

Although the power of the Internet is often exaggerated by enthusiastic Net activists — referred to as E-activists in the lingo of the Internet — what happened to the Net in Tunisia earlier, and now Egypt, has proved that the Internet is the first target of a regime on its last legs.

Although the power of the Internet is often exaggerated by enthusiastic Net activists — referred to as E-activists in the lingo of the Internet — what happened to the Net in Tunisia earlier, and now Egypt, has proved that the Internet is the first target of a regime on its last legs.

In Iran, relatively less extreme measures were used. The authorities there indulged in targeted filtering, blocking access to specific sites such as Twitter, which were not only used for protests but also for mobilising activists for a specific cause.

However, what happened, or is still happening, in Egypt has been termed “unprecedented”. Egypt, in late January, virtually disappeared from the map when the Government shut all four international carriers that connect the country to the rest of the world.

Businesses, banks, Internet cafes, government offices – indeed, every single website in the country – was cut off from the rest of the world. All connections collapsed when the four main Internet Service Providers (ISP) — Link Egypt, Etisalat Misr, Vodafone/Raya, and Telecom Egypt — were cut off from access to the external world. Bloggers reported that the biggest blackout in the modern era of the Internet started shortly after midnight on January 28, by which time the popular protests had already started to peak.

What was different this time was that for the first time there was a complete nationwide blackout. In Tunisia, earlier, only “specific routes”, according to bloggers, had been targeted.

In Iran too, before Tunisia, the government had only intervened by making connections dreadfully slow.

One blogger, James Cowie, reported the “virtually simultaneous withdrawal of all routes to Egyptian networks in the Internet’s global routing table.”

Mass withdrawal

The mass withdrawal of Border Gateway Protocols (BGP), which set the common ground rules for routing information among service providers in the Internet, resulted in virtually no Internet address anywhere in the world being reachable from Egypt. The complete ban on all traffic to and from the country was, according to Cowie, “unprecedented” in Internet history.

“This sequencing looks like people getting phone calls, one at a time, telling them to take themselves off the air,” observed Cowie. He suggested that it was unlikely that the blackout was “automated.” “Instead, the incumbent (ISP) leads and other providers follow meekly one by one until Egypt was silenced,” he remarked.

The lesson from Egypt is ominous. One can imagine the consequences for a modern economy, the media and for every facet of life when the Internet is suddenly shut down. Interestingly, activists observed that the Egyptian conglomerate, the Noor Group, escaped the shutdown.

There has been speculation that the group survived the blackout because of its connections to the Egyptian ruling elite. In fact, Cowie pointed out that the Egyptian Stock Exchange survived the blackout and remained on Noor’s website. However, even Noor went down on January 31.

According to Renesys, which provides ‘Internet intelligence’ and data on Internet operations, service from Noor started disappearing on January 31 and are “completely unavailable at present.” Among Noor’s clients are entities that are central to the country’s finance industry – the stock exchange, the Commercial International Bank of Egypt and the National Bank of Egypt.

Internet activists have pointed out that Egypt’s importance as a node in traffic between Europe and Asia has compounded problems. In particular, the Gulf states depend vitally on the Egyptian fibre optic link for access to information from global commodity markets, particularly oil.

Dismay

One blogger from Egypt remarked: “I have to say I’m deeply dismayed at how quickly the government can quickly cut off my hosting service for Egypt. Prior to today Egypt was the #1 place to do hosting for Europe-based users, as it is so cheap, responsive, and seemingly business friendly.”

Another blogger from Cairo remarked: “I am guessing (the) blackout is an attempt to disrupt protesters’ and activists’ ability to coordinate, not to prevent information from leaking out (after all, journalists are still allowed to operate).”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.