By: *Michael Wahid Hanna

By: *Michael Wahid Hanna

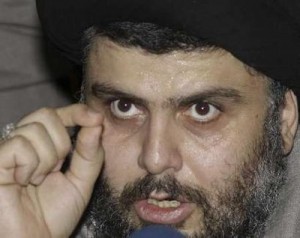

Iraq’s seven-month political deadlock looks to be entering a new phase, thanks in part to anti-American cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki received the support of the Sadrist political wing earlier this month, likely ensuring another term for Maliki but also giving Sadr, who has been living in exile in Iran since 2007, an important voice in the country’s political future.

For many in the U.S., what should be cause for relief and hope that the current impasse may be coming to an end has instead produced fear and suspicion over Iran’s influence in Iraq. Americans on the political right and left are warning that Iran has engineered this political about-face and that Sadr’s rise will cement Iran’s role as the chief architect of Iraqi politics. Not only does this misunderstand the fundamental nature of Iran-Iraq relations, it repeats a mistake we have made repeatedly since the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. U.S. exaggeration of Iran’s influence in Iraqi politics isn’t just hyperbolic and misguided, it actually makes an independent and Iran-resistant Iraq less likely.

Clearly, for the U.S., the rise of Sadr’s followers is less than ideal. Their unbending hostility to the U.S. has included armed conflict with the U.S. military: the Mahdi Army fought major battles against American forces, opened up a two-front insurgency, and fuelled the country’s descent into sectarian civil war.

So it’s understandable why so many in the U.S. are worried about Sadr’s political inclusion. U.S. Ambassador to Baghdad James F. Jeffrey even responded with a public warning that Sadr’s involvement might jeopardize U.S.-Iraq ties. However, the Sadrists, who primarily represent the Shiite poor, are an enduring feature of Iraq’s political landscape and secured their current position legitimately through the democratic process.

For many here in the U.S., concern over the Sadrist role is, at root, based on a simplistic understanding of Iran’s role in Iraq. But Sadrist political participation cannot be ascribed merely to the machinations of Iran. While linked to Iraq by ties of history, commerce, and religion, observers in the U.S. have often ascribed the Islamic Republic with near-magical powers to orchestrate events within its war-torn neighbor’s borders. However, Iran’s role in post-invasion Iraq has often been destructive. At various junctures Iran has emphasized inflicting damage to the U.S. by giving money, advice, and training to various Shiite militia groups in Iraq, including the Sadrist Mahdi Army. These actions have eroded their influence in Baghdad political circles and increased suspicions of Iranian motivations.

Recent Iraqi history should make clear that Iran cannot force its desired policy outcomes on Iraq, where lack of cohesiveness among the dominant Shiite factions threatened Iran’s goal of a friendly, Shiite-led government in Baghdad. The pre-election decision by Maliki to run independently thwarted Iran’s hopes of seeing a unified Shiite list contesting the elections and ensuring Shiite preeminence. It should also speak volumes that Iran’s closest ally among the Shiite political parties, the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, is now the most recalcitrant party to Maliki’s retention of power. The Iranian desire for Shiite cohesion was also set back by Maliki’s March 2008 Basra offensive against the Mahdi Army and other irregular Shiite militias supported by Iran. This intra-Shiite military confrontation clearly demonstrated Iran’s lack of actual control over its purported allies in Iraq. The offensive was a turning point for Maliki, bolstering his reputation as an independent nationalist who is focused on law and order. Iran can help shape events but cannot force Iraqi political figures to act contrary to their own perceived interests.

Our perception of Iran as the puppet master of Baghdad is rooted in decades of enmity between the U.S. and Iran, which continue today. Also, Iran’s broad support for Hezbollah in Lebanon and its monetary support for Hamas in Gaza makes it easy to imagine Iran replicating this strategy in Iraq. But the biggest factor in our willingness to see exaggerated Iranian influence in Iraq is something much simpler: partisan U.S. politics. For years, both parties have exaggerated Iran’s role to score political points. Iran hawks on the right have done so to bolster their case for greater U.S. hostility to the perceived Iranian menace. During the 2008 presidential primaries and general election, Republicans also used the threat of Iranian encroachment to argue against any drawdown in Iraq. Today, they maintain this line in attacking President Barack Obama’s Iraq policies as strengthening Iran. Meanwhile, voices on the left have, since the 2003 invasion of Iraq, latched onto to the notion of an unstoppable Iran expanding its influence throughout the region. This extension of the recriminations against the Iraq war, much like the conservative criticism of Obama, is an effort to further discredit President George W. Bush’s invasion by accusing him of ceding Iraq to Iran. This distortion on both sides is unfortunate because it paints Iraq as a mere prop for the purpose of polemics and because it is unmoored from the more prosaic reality of contemporary Iraq.

It is true that the toppling of Saddam Hussein was a strategic windfall for the Islamic Republic, but it has not allowed Iran to dictate Iraq’s agenda. Iraqi nationalism and suspicion of Iranian intentions, nearly universal in Iraq, simply do not allow for the kind of Iranian power one hears about in the U.S. While Maliki and Sadr’s ascent in Baghdad are in line with the Iranian desire for Shiite Islamist supremacy, their rise is a reflection of Iraq’s demography and politics. Of course a Shiite-majority, Islamist-leaning country will elect a Shiite-majority, Islamist-leaning government. Unfortunately, this is how democracy works in a war-scarred country where ethno-sectarian identity remains stubbornly vital to political affiliation. Sadr’s political participation, though it may make Iraq less likely to follow every American interest, is simply a reflection of the realities of Iraq’s nascent, flawed democracy.

Vilifying and exaggerating Iran’s role in Iraq will cloud U.S. perception of both countries and runs the danger of contributing to the formulation of bad policy. Simplistic notions of Iranian hegemony will poison U.S.-Iraqi bilateral relations, with each development judged in blunt zero-sum terms of whether it benefits the U.S. or Iran. In assuming such inherent conflict, the U.S. will be tempted to try to use Iraq as an American proxy in a broader struggle against Iran. This would serve no useful purpose; why wage a proxy war where none exists? Worse, it would weaken Iraq and enable the very Iranian influence we are so afraid of. In fact, American and Iranian long-term interests converge in Baghdad to a great extent. At root, both countries need a stable Iraq.

While still dependent to a large degree on outside assistance, thus prone to interference and meddling, Iraqis are not interested in being a puppet of either the U.S. or Iran. Pushing a proxy conflict and asking Iraq to be a front-line pillar in the wider regional struggle against Tehran would subordinate Iraqi interests to those of United States, alienate Iraqis, and potentially undermine Iraq’s relative stability.

The U.S. understands well the importance of not excluding segments of Iraq from political participation, and is concerned rightly over the potential deleterious effects of locking out major Sunni parties from the incoming government. As such, the U.S. would also be ill-served by seeking to isolate the Sadrists. While the legacy of the Mahdi Army is distasteful for the U.S., the experience of the Sunni Awakening is instructive as it involved close U.S. cooperation with and support for former insurgents with American blood on their hands. Following the success of the Sunni Awakening, it should not seem far-fetched for the U.S. to contemplate engaging with an Iraqi government with Sadrist representation.

The Iraqis want and need good relations with both the U.S. and Iran. Geography is immutable, and a relatively weak Iraq cannot afford a hostile relationship with its larger neighbor. Iran’s role in Iraq going forward will evolve as the U.S. military presence recedes. The imperative of stability should, in fact, dictate that the U.S. encourage good but proper relations between Iraq and Iran. In this vein, the U.S. should shield Iraq, to the extent possible, from the U.S.’s struggles with the Iranian regime. The U.S. should once again open direct channels of communication with Tehran to discuss issues of mutual concern regarding Iraq and, at the very least, should seek avenues for indirect cooperation where preferences are aligned. If the U.S. exacerbates conflict with Iran in Iraq, it risks making that tension all the more difficult to manage and ultimately handing Iran greater influence in Baghdad than any number of Muqtada al-Sadrs could ever provide.

*Michael Wahid Hanna is a fellow and program officer at The Century Foundation where he focuses on issues of international security, human rights, post-conflict justice, and U.S. foreign policy in the broader Middle East.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.