Hosni Mubarak is unlikely to have been too badly discomfited by Barack Obama’s expression of mild disappointment at the renewal of Egypt’s controversial emergency law. But it will still have been a useful reminder to the ra’is (president) that Washington does have real concerns about the governance of the Arab world’s most populous country – and is ready to express them publicly.

Nor were Egyptian opposition activists surprised at the move by a supine parliament dominated by the ruling National Democratic party: the emergency law, first imposed back in 1967, has been in force ever since Anwar Sadat was assassinated in 1981 (a good reminder of the old adage that there is nothing so permanent as the temporary), so it is a key part of a landscape in which political groups and individuals are routinely targeted and silenced in the name of national security.

Beatings and arrests at pro-democracy rallies are the grimly familiar face of Egyptian repression, as are detention without trial and prosecutions in state security courts with no right of appeal. The most usual suspects are the Muslim Brotherhood, the largest and most credible of opposition forces.

Nervousness about blanket renewal of the law – and the US response – was apparent in official insistence that henceforth it would be restricted to terrorism and drug-trafficking and would no longer allow censorship or closure of newspapers or other media or monitoring private correspondence and phone calls. “The emergency law will not be used to undermine freedoms or infringe upon rights if these two threats are not involved,” pledged the prime minister, Ahmed Nazif.

Critics say these assurances failed to persuade on two counts: the promise had been made before but never implemented; and the powers retained would still be used to suppress dissent.

“People have been arrested under the emergency law for a range of issues including freedom of speech and cases of freedom of religion,” said Soha Abdelati of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. “It’s common for the interior ministry to abuse all its privileges under the emergency law, so as long as the law is applied there are not enough guarantees that abuses won’t take place.”

Egyptian dissidents, bloggers and journalists see few grounds for optimism.

Pre-emptive spin included normally somnolent Egyptian embassies abroad springing into action with briefing papers and explanations. Delay in passing new dedicated anti-terrorist legislation, as long promised, was compared to Obama’s failure to close down the Guantánamo Bay detention camp. The message from Cairo: “We, too, have liberal instincts but you have to be tough and realistic when dealing with terrorism.”

The Egyptian government is certainly used to playing the terrorism card. Sadat, after all, was gunned down by the Islamic Jihad organisation, forerunners and co-founders of al-Qaida, enraged at his peace treaty with Israel. George Bush’s post-Iraq “forward strategy of freedom” in the Arab world faded after 2005, giving way to a renewed respect for stability, the status quo and massively unfree elections. Recent plots by Lebanon’s Hizbullah and action in support of Hamas in the besieged Gaza Strip have been tirelessly highlighted as threats to national security. Egypt’s enemies, after all, are the enemies of America – and Israel.

So it was interesting to see that the US decided to play this one differently. Perhaps one reason for the expressions of disappointment and regret from the White House and state department is that it will soon be a year since Obama gave his resonant address to the Muslim world from Cairo, when he faced criticism that the choice of venue meant legitimising Mubarak’s authoritarian regime – the recipient, after all, of the largest amount of US foreign aid of any country other than Israel.

The president’s language then was careful but easy enough to decode: “I do have an unyielding belief that all people yearn for certain things: the ability to speak your mind and have a say in how you are governed; government that is transparent and doesn’t steal from the people; the freedom to live as you choose.”

Urging Egypt to respect human rights while fighting terrorism is no abstract question: the extension of its emergency law comes ahead of parliamentary elections later this year and presidential elections set for 2011 against a background of feverish speculation about Mubarak’s health and likely successors.

Mohammed ElBaradei, the former head of the UN nuclear watchdog, now back home and campaigning for reform, calls the law a recipe for stagnation. Other opposition figures warn they will boycott the elections unless it is repealed. Last year the Muslim Brotherhood contemptuously dismissed Obama’s speech as a PR exercise: he is right to have served notice that he meant what he said about freedom. Guardian

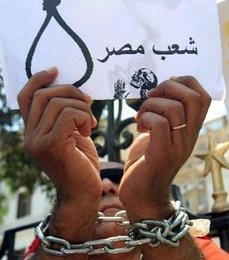

Photo: An Egyptian political activist holds up a sign which reads in Arabic “the people of Egypt” next to a drawing of a noose and a human skeleton during a demonstration organized by the banned Muslim Brotherhood and other opposition groups in downtown Cairo.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.