No model of jet has recorded twin disasters so soon after introduction, first with Lion Air and now with Ethiopian Airlines. Is there a common cause?

No model of jet has recorded twin disasters so soon after introduction, first with Lion Air and now with Ethiopian Airlines. Is there a common cause?

By : Clive Irving

There is no case in the recent history of commercial aviation where within the first year of introducing a new model jet there have been two serious fatal accidents involving that model. But that is now the record of the Boeing 737 MAX-8, the newest version of the most widely used single-aisle jet in the world.

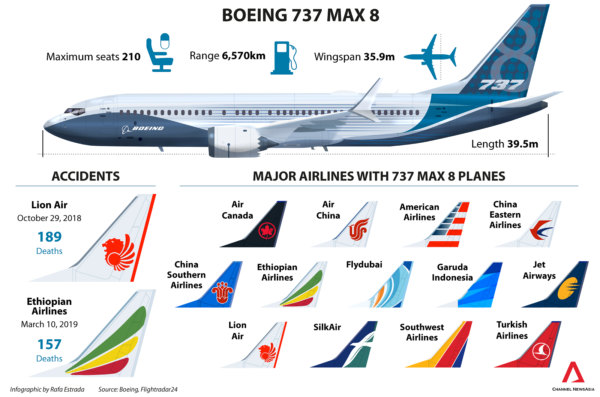

The crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 shortly after taking off from Addis Ababa occurred little more than four months after the crash of Lion Air Flight 610 in Indonesia. A total of 346 people died in the two crashes, 157 in Ethiopia and 189 in Indonesia.

Eight Americans, 18 Canadians, and passengers from at least 35 countries died in the crash of Flight 302, bound for Nairobi, Kenya.

A conclusive explanation for the Ethiopian crash cannot be reached without recovery of the data from the airplane’s black box. And, even though there are striking similarities between the two disasters, it is too soon to conclude that the cause was exactly the same.

Nonetheless it must be of great concern that at a time when the rate of fatal air crashes has been reduced to record low levels two such catastrophes can occur involving a new model jet that has only recently joined airline fleets: the Lion Air 737 was delivered in August 2018 and the Ethiopian 737 in November 2018.

The most pressing question for investigators is whether the Ethiopian pilots confronted the same sudden emergency that doomed the Lion Air flight.

Within a few minutes of takeoff the Lion Air pilots encountered a problem that made it difficult to control the climb. Due to a faulty instrument, the 737’s automatic flight controls system detected an aerodynamic stall and forced down the airplane’s nose to correct it.

In fact, the jet was nowhere near to stall speed and for the rest of what was only an 11-minute flight the pilots struggled to overcome the automated commands that continued to force down the nose. They lost that struggle and the jet nosedived into the Java Sea.

The Ethiopian 737 was in the air for far less time, around six minutes. But in that time the captain, like the Lion Air captain, reported difficulties and requested a return to the airport. Unlike the Lion Air flight there is no evidence that the Ethiopian crew was able to maintain altitude and began to make a turn back toward the runway – the jet’s end was very sudden and it appears to have impacted the ground at high speed.

Addis Ababa airport operates at what is technically called “hot and high” conditions – the runway is at a height of more than 7,600 feet above sea level and in a location where temperatures are often high. This means that the air is thinner than at usual ground levels and airplanes need a longer takeoff run.

So although Ethiopian Flight 302 reached a height of around 9,000 feet above sea level its actual height when it hit trouble was around 2,500 feet above the ground – the Lion Air jet first encountered a control problem at 1,000 feet, when it fell suddenly about 600 feet, and never rose above 5,000 feet.

There is a difference in the immediate history of the two flights. Pilots who flew the Lion Air jet on its previous flight had reported problems with the controls. While that airplane was between flights the airline’s maintenance crew checked it and reported it safe to fly – without, apparently, detecting the fault in a sensor that triggered the computers to force down the nose.

According to a press conference held by Ethiopian Airlines’ CEO, Tewolde Gebre Mariam, the airplane had undergone normal safety checks after a flight from Johannesburg, South Africa, in preparation for the flight to Nairobi, and no problems had been reported.

At the heart of the concerns about the MAX-8 is a change in the automatic flight controls. Boeing is facing a lawsuit on behalf of the family of a victim of the Lion Air crash that focuses on changes made to the flight controls in a few lines of new software.

The change, called Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, MCAS, initiates the nose-down command without input from the pilots. The introduction of this system was not included in the flight manuals issued to pilots nor was it included in the training given to pilots who transferred to the MAX-8 series from earlier model 737s.

THE DAILY BEAST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.