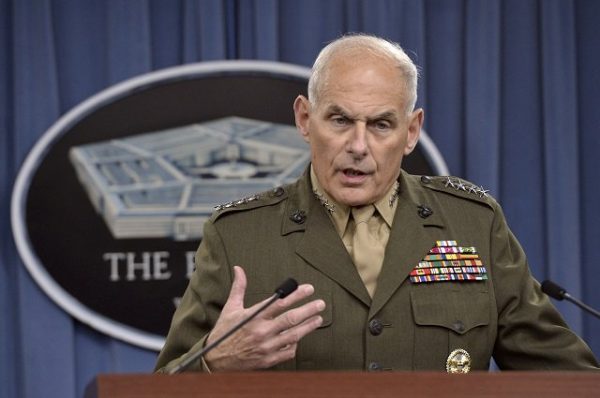

President-elect Donald Trump has chosen retired Marine Gen. John F. Kelly to run the Department of Homeland Security, turning to a blunt-spoken border security hawk who clashed with the Obama administration over women in combat and plans to close the prison at Guantanamo Bay, according to people familiar with the decision.

Kelly, who retired in February as chief of U.S. Southern Command, would inherit a massive and often troubled department responsible for overseeing perhaps the most controversial part of Trump’s agenda: his proposed crackdown on illegal immigration. DHS is the third-largest Cabinet department, with more than 240,000 employees who do everything from fight terrorism to protect the president and enforce immigration laws.

Kelly, 66, is a widely respected military officer who served for more than 40 years, and he is not expected to face difficulty winning Senate confirmation. Trump’s team was drawn to him because of his southwest border expertise, people familiar with the transition said. Like the president-elect Kelly has sounded the alarm about drugs, terrorism and other cross-border threats he seems as emanating from Mexico and Central and South America.

Yet Kelly’s nomination could raise questions about what critics see as Trump’s tendency to surround himself with too many military figures. Trump has also selected retired Marine Gen. James N. Mattis for defense secretary and retired Lt. Gen. Michael T. Flynn as national security adviser, while retired Army Gen. David Petraeus is under consideration for secretary of state.

Kelly, a Boston native, was chosen over an array of other candidates who also met with Trump after his surprise election victory last month. Those in contention included Frances Townsend, a top homeland security and counterterrorism official in the George W. Bush administration; Milwaukee County sheriff David Clarke and Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach. Clarke and Kobach are vocal Trump backers, with Kobach being nationally known for his strong views on restricting illegal immigration.

In the end, people familiar with the transition said, the choice came down to Kelly and Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Tex.), chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee. McCaul was considered an early favorite, but his chances were hurt by opposition from some conservatives who found him insufficiently tough on border security, the people said.

Known inside the Pentagon as a thoughtful man who continued serving his country even after his son was killed in combat, Kelly has talked in stark terms — much like Trump — about the threats America faces in the Middle East and beyond. In speeches, he has expressed frustration with what he calls the “bureaucrats” in Washington, and he described the military’s counterterrorism operations abroad as a war against a “savage” enemy who would gladly launch more deadly attacks.

“Given the opportunity to do another 9/11, our vicious enemy would do it today, tomorrow and everyday thereafter,” Kelly said in a 2013 Memorial Day address in Texas. “I don’t know why they hate us, and I frankly don’t care, but they do hate us and are driven irrationally to our destruction.”

His blunt manner led to conflicts within the Obama administration, where he served more than three years as Southern Command chief — overseeing military operations across Central and South America — and as senior military adviser to defense secretaries Robert M. Gates and Leon E. Panetta.

Kelly opposed Obama’s failed plans to close Guantanamo, people familiar with his views say, and he has strongly defended how the military handles detainees. In a 2014 interview, he told The Washington Post that criticism of their treatment by human rights groups and others was “foolishness.’’

He also publicly expressed concerns over the Pentagon’s order in December that for the first time opened all jobs in combat units to women, including the most elite forces such as the Navy SEALs. “They’re saying we are not going to change any standards,” Kelly told reporters at the Pentagon. “There will be great pressure, whether it’s 12 months from now, four years from now, because the question will be asked whether we’ve let women into these other roles, why aren’t they staying in those other roles?’’

On the personal side, Kelly learned firsthand the pain and loss suffered by many military families. His son, 2nd Lt. Robert M. Kelly, died in Afghanistan fighting the Taliban in 2010. Four days later, the general delivered a passionate and at times angry speech about the military’s sacrifices and its troops’ growing sense of isolation from society.

“Their struggle is your struggle,” he told a crowd of former Marines and business people in St. Louis. “If anyone thinks you can somehow thank them for their service, and not support the cause for which they fight – our country – these people are lying to themselves. . . . More important, they are slighting our warriors and mocking their commitment to this nation.”

He never mentioned his son by name. The speech has been passed around the Internet ever since.

As DHS secretary, Kelly would take on what is considered to be one of Washington’s most challenging jobs, in part because of the agency’s persistent management problems and employee morale that is among the federal government’s lowest.

Although DHS was created after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks primarily to coordinate the battle against terrorism, it is now perhaps equally known for its immigration role. Trump has pledged a crackdown on illegal immigration that would require an expensive and logistically difficult operation to remove millions from the country.

That work would be overseen by DHS components such as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which Trump has proposed to beef up by tripling the number of agents. U.S. Customs and Border Protection, also part of DHS, is also likely to come under increased pressure in the Trump administration to better secure the Southwest border.

Perhaps Kelly’s most visible role would be to help oversee Trump’s signature campaign promise: a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to keep out illegal immigrants. Trump has said the construction will be easy, but experts say the structure would face numerous obstacles, such as environmental and engineering problems and fights with ranchers and others who would resist giving up their land.

The president-elect and his homeland security secretary appear to be in synch on cross-border threats.

In congressional testimony last year, Kelly said the Southern Command was “just barely” able to keep on the “pilot light of U.S. military engagement” in the border region, and he warned that existing smuggling routes into the United States could be used by terrorist groups.

“Despite the heroic efforts of our law enforcement colleagues, criminal organizations are constantly adapting their methods for trafficking across our borders,” Kelly told the Senate Armed Services Committee. “While there is not yet any indication that the criminal networks involved in human and drug trafficking are interested in supporting the efforts of terrorist groups, these networks could unwittingly, or even wittingly, facilitate the movement of terrorist operatives or weapons of mass destruction toward our borders.’’

Kelly’s thoughts on other controversial issues, however, have been markedly more measured than Trump’s. While the president-elect once called for a ban on all Muslims entering the United States, Kelly has said U.S. troops “respect and even fight for the right of your neighbor to venerate any God he or she damn well pleases.”

He has also has stressed the importance of enforcing human rights, and told military commanders in Latin America that they revert to the past and overthrow civilian leaders with whom they disagree.

“Since 1945, no one in the U.S. military has liked the end result of the military conflicts we’ve been in: Vietnam, Korea, certainly Iraq, and probably Afghanistan,” Kelly said in a 2015 discussion at the Pacific Council on International Policy. “But in a democracy, you salute. You suck it up. . .You cannot act.’’

Earlier in his career, Kelly served as the assistant commander of the 1st Marine Division under Mattis during the initial invasion of Iraq in 2003. He returned there again in 2004, and a third time in 2008, when he was named the top U.S. commander in western Iraq. Before becoming a general, Kelly served as a special assistant to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s supreme allied commander for Europe, working from Belgium.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.