The recent discoveries of massive gas fields off the coast of northern Israel, tantalizingly close to Lebanese coastal waters, has stirred cash-strapped Lebanon to accelerate efforts to begin its own oil and gas exploration.

But the prospect of previously undiscovered fossil fuel riches off the coasts of Lebanon and Israel risks becoming a new source of conflict as well as an economic windfall for the two warring neighbors.

“This is something big and potentially landscape-changing economically, financially, and politically,” says Nassib Ghobril, head of economic research and analysis at Byblos Bank in Beirut.

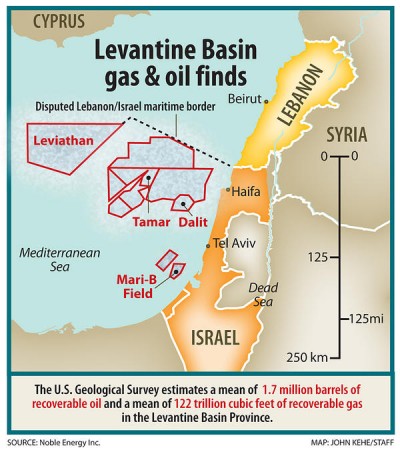

Last year, a US-Israeli consortium discovered the Tamar gas field 55 miles off the coast of northern Israel, which contains an estimated 8.4 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas – the largest natural-gas find in the world in 2009. Earlier this year, a field called Leviathan was discovered in the same area with an initial estimate of 16 trillion cubic feet of gas.

But there are likely more untapped fields; the US Geological Survey (USGS) said in March that the Levantine Basin, which includes the territorial waters of Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and Cyprus, could hold as much as 122 trillion cubic feet of gas – and 1.7 billion barrels of oil.

But there are likely more untapped fields; the US Geological Survey (USGS) said in March that the Levantine Basin, which includes the territorial waters of Lebanon, Israel, Syria, and Cyprus, could hold as much as 122 trillion cubic feet of gas – and 1.7 billion barrels of oil.

Indebted Lebanon

Israel, which could become energy self-sufficient if results meet expectations, began test drilling the Leviathan deposit Oct. 18. The same week, Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri said that Lebanon was close to marking its maritime boundaries with neighbors Syria and Cyprus, which should allow oil and gas exploration licenses to be issued by early 2012.

The prospect of oil and gas beneath Lebanon’s coastal waters could have immense benefits for a country short on natural resources and encumbered with one of the highest debt rates in the world, around $52 billion or 147 percent of gross domestic product.

But Mr. Ghobril, the economic analyst, cautions that it is too early to anticipate an oil and gas boom for Lebanon.

A draft bill on energy exploration passed by the Lebanese parliament in August deferred politically sensitive aspects such as deciding on the regulatory body and how to handle any revenues. Lebanon’s notoriously turgid bureaucracy and political infighting could also delay the process.

“All of this precedes any positive tangibles in that regard,” he says. “The key point is to see how much of [the gas and oil] is economically recoverable. We might all be disappointed but we might also be pleasantly surprised.”

Brewing dispute

The maritime border between the two countries has never been delineated because they have officially been at war since Israel declared independence in 1948.

Israel says its gas concessions lie within Israeli waters, but it remains unknown whether the gas field extends to beneath Lebanon’s territorial waters. The Lebanese government recently handed to the UN documents marking what it believes is the correct path of Lebanon’s maritime border with Israel.

In the absence of a mutual agreement on the border and division of resources, Israel could follow the “right of capture” rule, which allows a nation to extract oil or gas from its side of the border, even if the reserves stretch into another country’s territory.

Some Lebanese politicians have accused Israel of attempting to steal Lebanon’s oil and gas resources, and militant Shiite Hezbollah has sworn to use its weapons to defend them. Israeli officials have warned of retaliation for attacks on its oil and gas facilities.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea offers specific guidelines for maritime borders, but Israel is not a signatory to the convention. “It requires mutual recognition of those borders,” says Gal Luft, executive director of the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security in Washington. “So this will require the two sides to sit down and agree on this, which I don’t see happening.”

UN unlikely to wade in

The UN has been here before. In 2000, when Israeli troops in south Lebanon were supposed to withdraw to satisfy UN resolutions, the UN created a “Blue Line” conforming to the Lebanese/Israeli border. The UN insisted that the Blue Line had no legal standing but was simply a measure for Israel’s troop pullout. However, the delineation process took longer than planned because neither side was willing to concede an inch of territory.

Israel has placed buoys where it believes the sea border lies, and routinely defends it with armed force. The UN does not recognize the line as legally binding, but the naval component of the UN peacekeeping force in south Lebanon observes a 1.25-mile buffer north of the line to avoid potential confrontations with the Israeli navy.

While the UN’s International Court of Justice has ruled on maritime borders in the past, analysts doubt that the UN will risk becoming embroiled in another boundary dispute between Lebanon and Israel – especially with potentially billions of dollars of oil and gas revenue at stake.

“It’s an extremely complicated process to delineate a maritime border, and I don’t think the UN will become involved in that,” says Timur Goksel, a former senior official with the UN peacekeeping force in south Lebanon. “They haven’t even finished marking the Blue Line on the ground.”

By Nicholas Blanford

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.